What's new in exploration

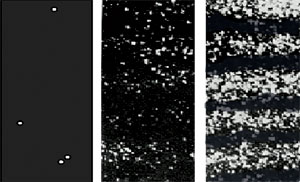

The weirdest thing that I know. This month, I take a break from all things geological to communicate, in 800 words, something that cannot readily be explained. Two centuries ago, Thomas Young designed what is probably the most famous and elegant experiment in history, as shown below (top). A light source (S) spreads out and passes through two slits (a and b). Depending on their spacing, the light’s wavelength, and the distance (L) to a screen or film (F), an interference pattern of stripes appears, as shown on the right. This experiment can be duplicated using water waves. This, together with the fact that the math is the same for both water and light (and sound waves), proves that light is a wave. Later, the experiment was repeated, only this time, smoked glass was stacked in front of the light source, S. After a time-exposure of the film, only one dot appeared and, after more time, a few more apparently random dots (bottom left panel). Unfortunately, this contradicted the earlier finding that light was a wave, and proved that light was composed of discrete particles called photons. Worse, when the smoked glass experiment was allowed to proceed for a long time, it became obvious that the random dots were not random at all, but instead gradually formed an interference pattern (bottom right panels). This result would seem to be impossible. It means that a single photon can ostensibly go through one slit, but nevertheless have knowledge of the other slit, such that it will not expose the film in the dark striped areas. If one of the slits is covered, dots still appear on the film, but they will not form a pattern. Not fully understanding this conundrum, scientists labeled it particle-wave duality. Young’s experiment has intrigued scientists for centuries. This is because of the inherent nonsense of saying that, say, a baseball, is exactly the same as a tsunami wave, and then “explaining” it by labeling it baseball-tsunami duality. Quantum mechanics explains it in terms of a wave function, which, in effect, allows something to be in two places at the same time. Quantum mechanics is truly an acquired taste. One consequence of Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle is that you cannot know which slit the photon went through and still produce an interference pattern. Einstein did not like the explanation for this fact, and thousands of physicists have spent millions of dollars and years of their lives trying to get around it by detecting, with evermore sophisticated means, which slit the photon goes through, while preserving the interference pattern.

As a student, the full import of Young’s double-absurdum-slit experiment hit me rather hard. Such a contradiction in rational thought did not sit well with me. After the professor gave his presentation, I asked, “Wouldn’t that normally be considered impossible?” “Yes,” was all that he said. I don’t know if I was the only one in that class of 12 who “got it,” or who was bothered by this, but the next day, a bit dazed, I went looking for an explanation. (In a way, I’m still searching. I’ve just gotten used to accepting the truth of quantum mechanics.) I approached the first researcher: “I’m trying to reconcile Young’s double slit. How do you picture a photon?” He answered, “I try not to. It’s natural to form a mental image of something physical, something you’re trying to understand, and make a model, but if you do that with a photon (or an electron or atom), you’ll be wrong. Try hard not to picture it.” “What is this, Zen? Keeping the human mind blank, model-free, doesn’t seem possible,” I said. I approached another professor with the same question. He answered, “If you work with particles long enough, you’ll get used to it.” I approached a third professor, pleading to make sense of what, by now, clearly made no sense. He gave me a long, deep look. And with a fatherly hand on my shoulder, offered only these words, “Ah, I see you’ve arrived. Welcome to the club.” Stunned for awhile, finally, I understood. Certainty, the basic sense of my everyday world, and the solace that I take from these, do not exist in the quantum world of the very small. The nature of nature is, well, unnatural. And I should not try to relate to it. I take some comfort in knowing that thousands of others have been similarly disturbed by this. I now realize the likely explanation that allows this aspect of Heisenberg’s Uncertainty to be true: As bizarre as it may seem, it’s the act of knowing that’s prohibited. Thus, you can set up counters, detectors and cameras on each slit, and, as long as you are wearing a blindfold, these will faithfully record which slit the photon went through and allow an interference pattern to form. However, the instant that you remove the blindfold, the counters will reset, the film will un-develop, or the interference pattern will disappear. The underlying reason for this is because photons are actually sentient beings with a kind of narrow intelligence, a sort of photonic idiot savant. In the case of Young’s experiment, they can split in half before going through both slits, meet afterward, discuss the distance between the slits and to the back screen, then recombine and impact the screen in a spot that will eventually become part of an interference pattern. They do this intentionally, solely to infuriate scientists. The evil bastards.

|

||||||||||

- Quantum computing and subsurface prediction (January 2024)

- Machine learning-assisted induced seismicity characterization of the Ellenburger formation, Midland basin (August 2023)

- What's new in exploration (March 2023)

- Seismic and its contribution to the energy transition (January 2023)

- What's New in Exploration: Rocks can save or kill the planet (July 2022)

- Processing of a large offshore 3DVSP DAS survey in a producing well (June 2022)

- Applying ultra-deep LWD resistivity technology successfully in a SAGD operation (May 2019)

- Adoption of wireless intelligent completions advances (May 2019)

- Majors double down as takeaway crunch eases (April 2019)

- What’s new in well logging and formation evaluation (April 2019)

- Qualification of a 20,000-psi subsea BOP: A collaborative approach (February 2019)

- ConocoPhillips’ Greg Leveille sees rapid trajectory of technical advancement continuing (February 2019)