Regional Report: Focus on Arctic oil and gas sharpened during 2025

GORDON FELLER, Contributing Editor

ARCTIC POTENTIAL

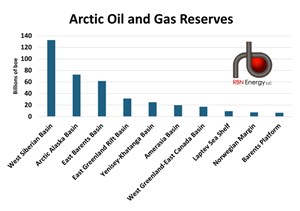

The Arctic is estimated to hold some of the world’s most valuable undiscovered oil and gas resources. According to a 2008 assessment by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), the most recent comprehensive estimate available, the region contains approximately 22% of the world’s undiscovered oil and natural gas reserves, an estimated 412 Bboe, with about 84% of those volumes located offshore and natural gas making up about two-thirds of the total. About 95% of Arctic resources are located in the 10 areas shown in Fig. 1. About one-third are located in Russia’s West Siberian basin (far-left bar), followed by the Arctic Alaska basin and the East Barents basin north of Russia, which also approaches the northern tip of Norway and Finland.

Next on the list is the East Greenland Rift basin, Russia’s onshore Yenisey-Khatang basin, the Amerasia basin north of the U.S. and Canada, and the West Greenland-East Canada basin. Rounding out the Top 10 are the Laptev Sea Shelf off the Russian coast, the Norwegian Margin off Norway, and the Barents Platform in the southern Barents Sea off Finland. Zeroing in on Greenland, the East Greenland Rift basin and the West Greenland-East Canada basin areas (Fig. 2) are thought to have a combined 48 billion boe, or 12% of the Arctic total.

ENVIRONMENTAL ASPECTS

For its part, the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA’s) latest “Arctic Report Card” (https://arctic.noaa.gov/report-card/report-card-2025/) seems to confirm the worries of observers and analysts: The region is warming much faster than the global average, causing dramatic shifts like melting glaciers, boreal fish moving in (displacing Arctic species), and rivers turning orange, due to thawing permafrost releasing iron and heavy metals, creating toxic runoff that kills aquatic life.

The NOAA report also notes sea ice decline, with the maximum sea ice extent in March 2025 being the lowest in 47 years of records. Changes in the Arctic, they say, are now actively influencing both global weather patterns and sea levels.

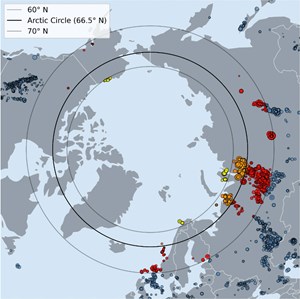

To comprehend the full scope of Arctic impacts, we talked with Mark Davis, CEO of Capterio, the UK-based flare solutions company that developed FlareIntel, a flare tracking service. “Flaring in the Arctic (i.e. latitude greater than 66.5o) is dominated by Russia (some 95% of the total), with a small contribution from the USA and then Norway, and accounts for some 4.3 Bcm,” according to Capterio’s analysis of World Bank data from 2024.

“With the exception of 2021, Arctic flaring is at an all-time high, having crept up over the last decade,” continues Capterio’s analysis “At modest notional prices of $5 per MMbtu, this represents a potential revenue upside of $800 million and perhaps up to 30 million CO2-equivalent tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions.” However, as Davis points out, “whilst Russia’s sanctioned Arctic LNG could be part of the solution, given its location, much of this flared volume will likely be challenging to bring to export markets, although there are probably opportunities to use recovered gas for location power needs, especially to displace local use of diesel.” Flaring at the sanctioned LNG plant is being watched closely by Capterio’s FlareIntel service.

Davis concluded the interview by noting that “if we take the flaring above 60oN, and then we add in flares from the UK and Canada, the figure then climbs to 19 Bcm per year, but it is still 98% dominated by Russia,” Fig. 3.

There’s an irony about climate changes, which have been caused by more than a century of non-stop burning of fossil fuels: Melting ice makes vast untapped oil, gas, and mineral resources more accessible, raising the strategic value of the entire Arctic region. At the same time, a less-icy Arctic opens up new shipping routes, which has major geopolitical and economic implications. Routes like the Northern Sea Route (NSR) can cut travel time significantly between Europe and Asia—by up to 40%, compared to the Suez Canal. Shorter distances mean lower fuel costs and potentially reduced greenhouse gas emissions. As a consequence, those countries with Arctic coastlines—like Russia, the U.S., Canada, and Norway—gain more influence over global trade routes.

ACTIVITY AND PROJECTS

While the ecological process unfolds, governments and companies are busy pushing forward with their plans. Summaries of the key points on upstream Arctic activity in 2025—and what to look for in 2026—were provided by Michael Moynihan, Research Director for Russia upstream oil & gas at Wood Mackenzie. According to Wood Mac figures, Arctic oil and gas production averaged 9.148 MMboed during 2025, including 8.110 MMboed in Russia, 490,000 boed in the U.S., and 419,000 boed in Norway, Fig. 4. By 2035, Wood Mac expects Arctic production to average 10.442 MMboed, including 9.570 MMboed in Russia, 640,000 boed in the U.S., 231,000 boed in Norway, and 1,000 boed in Canada.

Russia. State-controlled firm Rosneft’s Vostok Oil flagship 2-MMbopd project is not progressing as rapidly as it should, to meet its production target deadlines. In addition, ice-class shipping capability is negatively impacted by sanctions.

A decline in European gas demand continues to dampen activity. This is true at both gas fields onstream in the Yamal region, as well as those under development.

In addition, offshore exploration has largely disappeared since the invasion of Ukraine. There have been no major wells in Russian waters nor big discovery announcements. This is likely to continue in 2026, and a reversal of fortune is largely dependent on a ceasefire and implementation of a peace deal in the Russia/Ukraine war.

Meanwhile, expanded European and U.S. sanctions on Russia are likely to have a negative impact on oil and gas production in the Arctic if fully enforced. Absent a price and timing deal with China on the Power of Siberia 2 pipeline, gas from the Arctic region of Russia is unlikely to be needed anytime soon to fill the proposed pipeline.

Norway. The 500-MMbbl Johan Castberg oil field commenced production in 2025. This is only the second oil field to begin output in Norway’s Barents Sea and is Norway’s northernmost field. The Askeladd West gas field in the Barents Sea also began producing in 2025. It supports additional gas for Europe’s largest LNG liquefaction facility at Hammerfest.

Wildcat and near-field exploration activity has regained some momentum in Norway’s Barents Sea. Four discoveries totaling over 50 MMboe have been made so far in 2025, in the vicinity of the Goliat and Johan Castberg hubs.

Equinor announced an oil discovery in the Barents Sea. The company says that it discovered 9 MMbbl to 15 MMbbl of oil in its Johan Castberg permit in the Arctic Barents Sea, boosting reserves for this newly active region. Norwegian environmental groups have lodged a complaint at the European Court of Human Rights, challenging expanded Arctic oil permitting and arguing it violates human rights and climate obligations. Norway approved a new Barents Sea drilling permit in December 2023—even as domestic backlash grows over Arctic expansion.

A proposed 800-km (497-mi) gas pipeline linking the Barents Sea to infrastructure in the Norwegian Sea has prompted a search for additional gas volumes in the basin. However, recent exploration probes have failed to discover material volumes. Yet, a number of large prospects are set to be drilled over the coming years, which could shift the narrative.

Norway’s largest undeveloped arctic oil field, Wisting, still awaits a final investment decision (FID). Equinor remains committed to developing the field, but the revised FID target of 2026 seems ambitious.

The government has opened submissions for the 26th Licensing Round. The round offers more “frontier” acreage and includes a large, unexplored part of the eastern Barents. Interest might be limited, and it still might not go ahead, due to negotiations between the government and coalition parties.

Canada is not expected to have an active Arctic program in the near future, as no export routes are developed, and current economic focus is on oil sands, Montney tight gas and Newfoundland & Labrador’s offshore fields.

The Canadian Coast Guard is acquiring two polar icebreakers for delivery in the early 2030s as part of a wider Arctic investment effort. In addition, discussion of building out Churchill’s port is at an early stage.

Inuvialuit Petroleum Corporation is preparing to bring online the Tuk M-18 well to supply gas and diesel for its local community to replace the Ihkil well. Elsewhere, Imperial Oil continues to produce from the onshore Norman Wells field and has extended regulatory clearance to inject water after a recent spill event.

U.S.–Alaska. The Trump administration is looking to increase Alaska’s leasing, exploration and production activities and is updating regulatory processes. In addition, Glenfarne, a U.S.-based energy developer, is soliciting interest in a proposed Alaska LNG project, with Worley updating FEED and cost estimates.

Armstrong, APA and Santos will drill a new prospect and appraise the Sockeye discovery on the eastern North Slope. ConocoPhillips is shooting seismic and will drill up to four exploration wells on the NPR-A. Narwhal LLC is also planning new wells. The Nanushuk formation continues to deliver discovery success.

Meanwhile, Santos and Repsol will achieve first production at Pikka field while ConocoPhillips will have Willow construction over 50% complete, ahead of first oil in early 2029. These two key Nanushuk projects will reverse regional production declines and bring about new infrastructure for future developments on the western slope.

Greenland. Exploration of Greenland could be back on the table in 2026. For instance, U.S.-based March GL is preparing for two exploration wells in the onshore Jameson Land basin in eastern Greenland, targeting a combined 1.2 Bbbl of prospective resources. Any discovery would face significant viability challenges.

Operationally, Arctic drilling in such remote locations presents major logistical hurdles and high costs. With no sizeable local market, volumes must be large enough to justify expensive export infrastructure.

Politically, the timing is complex. A pro-independence party that supports reconsidering the new license ban won Greenland's March 2025 election. And U.S. company involvement adds fuel to the geopolitical flame.

One country not referenced by Moynihan is Japan, which is in preliminary discussions to potentially purchase LNG from a large-scale project in Alaska, with Japanese companies like JERA and Tokyo Gas signing non-binding letters of intent. These agreements are part of a broader trade package between the U.S. and Japan and could contribute to Japan's energy security, though the project faces significant financial and logistical challenges.

Both companies are considering purchasing 1 million tons of LNG per year. The letters of intent they signed with the project's lead developer, Glenfarne, are a first step to evaluate the feasibility and negotiate final terms, not a commitment to purchase. But the fact is that Japan’s political and business leaders see Alaskan LNG as a key part of their strategy to help Japan diversify its energy sources and reduce reliance on other suppliers. Transporting LNG from Alaska to Japan could take less than 10 days, compared to longer routes from the U.S. Gulf Coast. Alaskan LNG could be resold to other countries, providing more flexibility than some existing import contracts.

The project's high costs are a major obstacle, and government involvement or support may be needed to bring the price down. Furthermore, the project needs substantial investment and binding long-term contracts, which are difficult to secure, due to market volatility and competition. The project faces criticism over its climate impact and potential risks to Indigenous communities in Alaska.

In October 2025, U.S. Interior Secretary Doug Burgum announced that a key engineering and cost study for the proposed 800-mi gas pipeline in Alaska is expected to be completed by the end of this year. This study is crucial for the project's advancement.

The pipeline project has gained momentum under U.S. President Donald Trump, who has been advocating for increased development of fossil fuels in the U.S. The project aims to transport gas from Alaska's far north to the Gulf of Alaska. Glenfarne Corp. plans to decide on the pipeline project by early 2026. The company has hired Worley, the Australia-based engineering firm, to prepare a final engineering and cost estimate, a FEED study.

GOVERNMENTAL POLICIES AND GEOPOLITICAL STRATEGIES

Both the U.S. and Canadian governments are opening their federal lands and waters for drilling and doing so with much fanfare. At the same time, they’re both taking steps to reinforce the infrastructure—including pipelines and ports and harbors—to support it. Meanwhile, Norway continues to explore and drill in the Arctic, even amid domestic and international climate backlash. Not to be outdone, Russia persists with its own expansion program to grow its Arctic footprint. It is focused on Arctic LNG outputs despite sanctions, while deepening cooperation with China.

Russia is desperately trying to ramp up sanctioned LNG and Sino-Russian cooperation. Russia’s Arctic LNG 2 shipping surged in late June 2025, despite Western sanctions (See here in World Oil). China and Russia also expanded joint Arctic patrols and energy collaboration, including LNG and shipping routes.

Russia has been a dominant force in Arctic E&P; however, U.S. sanctions targeting the Russian energy sector — including major producers like Gazprom Neft and Surgutneftegas — following the 2022 invasion of Ukraine have disrupted operations and had the gradual effect of degrading Russia's energy sector. In response, Russia has intensified efforts to develop indigenous, Arctic-capable technologies, aiming to reduce its reliance on foreign expertise. This strategic shift has fostered closer ties with China, and Chinese firms hold substantial stakes in key projects, including 30% in Yamal LNG and 20% in Arctic LNG-2, a major initiative led by Russia’s Novatek and located on Russia’s Gydan Peninsula.

China, despite not being an Arctic nation, has lately been asserting itself as a “near-Arctic state,” with vested interests in the region’s energy resources. China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), which is that country’s largest state-owned oil and gas firm, has invested in several Russian Arctic energy projects. The aim has been to significantly strengthen China’s access to the region’s vast, largely untapped energy reserves.

Russia had hoped that its saving grace would come with CNPC’s acquisition of a 20% stake in Arctic LNG-2, which had been expected to produce substantial quantities of natural gas and LNG, with first production once slated for the mid-2020s. Novatek is Russia’s largest independent natural gas producer. The project—which was central to Russia's broader strategy to develop Arctic resources and strengthen its energy export infrastructure—was expected to have a production capacity of around 19.8 million metric tons per annum (MMtpa, 2.6 Bcfd), which would have made it one of the largest LNG projects globally. Its development was vital to President Vladimir Putin’s plan to tap into the region’s natural gas reserves, which are strategically positioned to serve markets in Europe and Asia.

The project’s plan included three liquefaction trains, each with an annual capacity of around 6.6 MMtpa. The first train was supposed to be commissioned in 2023, with the full project coming online by 2025; however, significant challenges have impacted its development and operational status. Western sanctions severely disrupted the project's progress and led to the suspension of liquefaction processes, with production halted in April 2024. The project has struggled to commerce commercial operations. The plan resumed natural gas processing at a low rate in early April 2025, but with its first LNG cargo still pending.

Compounding these issues, key stakeholders also withdrew from the project. Chinese engineering firm Wison New Energies announced in June 2024 its decision to discontinue all ongoing Russian projects, including those associated with Arctic LNG-2.

Canada revived the country’s once-shelved Arctic pipeline plans. In March 2025, Canadian PM Mark Carney reintroduced plans for Arctic pipelines linked to deepwater ports to diversify exports beyond the U.S.—though economic feasibility remains uncertain due to challenging terrain.

U.S. The strategic maneuvers by Russia and China in the Arctic prompted shifts in U.S. energy policy. These moves aim to counterbalance Russian and Chinese activities by asserting U.S. interests in Arctic energy resources. The Trump administration’s concerns did not stop at promoting private sector investment into tapping the Arctic’s oil and gas potential. It was back in October 2025 that Trump announced a deal with Finland to strengthen the U.S. Arctic presence. The terms are simple: the U.S. Coast Guard acquires four icebreaker ships built in Finland and constructs up to seven more in U.S. shipyards with Finnish expertise, Fig. 5. The 11-vessel fleet is expected to cost $6.1 billion, with the first ship to be delivered by 2028.

Simultaneous to what others are doing, U.S. government initiatives aimed at expanding Arctic drilling are being pushed. The U.S. Department of the Interior has been busy rolling back Biden-era protections to allow drilling across approximately 82% of the National Petroleum Reserve–Alaska (NPRA), including previously protected “special areas.” Previous U.S. efforts to expand Arctic drilling have been prone to a stop-and-start pattern. Under former President Barack Obama, Arctic drilling was limited, due to environmental concerns, and areas were withdrawn from oil leasing. Former President Joe Biden’s team had a both/and approach, sometimes saying yes and sometimes saying no.

Using a geology-based assessment methodology, the U.S. Geological Survey estimated mean volumes of 1.8 billion Bbbl of oil and 119.9 Tcf of gas technically recoverable from undiscovered, conventional accumulations in Cretaceous and Cenozoic strata of the North Chukchi basin. The USGS “Assessment of Undiscovered Oil and Gas Resources of the North Chukchi Basin, Outer Continental Shelf of the Chukchi and East Siberian Seas, Arctic Ocean, 2023” (https://pubs.usgs.gov/publication/fs20243015) was published as part of the National and Global Petroleum Assessment. (https://doi.org/10.3133/fs20243015)

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is being reopened. In particular, Trump’s January 2025 presidential Executive Order forced the reopening of ANWR to oil and gas leasing, reversing Biden-era protections that had canceled controversial oil and gas exploration and development leases.

It’s worth citing here some public statements from key oiland‐gas industry groups/leaders in response to Trump’s Jan. 20, 2025, executive order opening up drilling in the ANWR, and Alaska more broadly.

For instance, API President & CEO Mike Sommers, on Jan. 13, 2025, (just before the order), told reporters that his group expected the new administration to reverse the leasing ban in ANWR and offshore. “Oil prices are rising …,” opined Sommers. “When you take barrels off the market, you need new production, and it’s better to have that oil and gas from the U.S. than depending on OPEC and other producers.”

He also said that API “will defend that position in court…Americans sent a clear message at the ballot box, and President Trump is answering the call on day one — U.S. energy dominance will drive our nation’s economic and security agenda. This is a new day for American energy, and we applaud President Trump for moving swiftly to chart a new path where U.S. oil and natural gas are embraced, not restricted.”

In comments to the media on Jan 23, 2025, API Senior V.P. for Policy Dustin Meyers noted that the oil industry was unlikely to rush to Alaska, despite Trump’s call for drilling. “There is always the possibility that these areas will be closed after the next electoral cycle.…That could dampen the interest of oil companies to undertake new drilling projects in the near future,” added Meyers. This reaction highlights some caution from the industry, despite the policy reversal.

Meanwhile, in a Jan. 21, 2025, statement, Energy Workforce & Technology Council (EWTC) co-Presidents Tim Tarpley and Molly Determan said that “by rolling back burdensome regulations and prioritizing permitting reform, we can unlock the full potential of American energy production, create jobs, and provide affordable, reliable energy for consumers across the country.” After the order, they added that “President Trump’s decisive actions to unlock Alaska’s vast energy resources mark a pivotal moment for the U.S. energy sector.”

Sitting out there in the icy Arctic Ocean, Greenland is very much on President Trump’s mind. While national-security concerns are cited as the motivation behind the U.S.’s interest in acquiring the Danish territory, there is also potential access to the Arctic’s vast natural resources: oil, natural gas and critical minerals. Whatever the reasons, this is the first time in decades that the region and its energy potential have grabbed the attention of so many.

LNG FLOWS TO CHINA AND U.S CONCERNS

Increasingly problematic in 2025 was the flow of sanctioned Russian LNG from the Arctic LNG 2 project. Despite attempts to enforce sanctions, Arctic LNG 2 continued operations throughout 2025, dispatching numerous cargoes, primarily to China, and using an illegal and decrepit "shadow fleet" of tankers.

As reported by Reuters on Aug. 29, 2025, China received its first LNG cargo from Russia’s Arctic LNG 2 project, according to ship-tracking data from Kpler and LSEG. The tanker Arctic Mulan berthed at the Beihai LNG terminal in Guangxi, China, marking the project’s first delivery to an end-user since its startup last year. China was expected to receive four more shipments over a week’s time.

China’s acceptance of the first cargo from the Arctic LNG 2 project, paired with the recent Power of Siberia 2 pipeline agreement, signals a deliberate test of U.S. and EU sanctions enforcement and a deepening of Sino-Russian energy interdependence. For Russia, the delivery is as much political as commercial, demonstrating the resilience of its Arctic LNG ambitions despite technology, financing, and shipping constraints.

For China, incremental intake from Arctic LNG 2 diversifies gas supply amid volatile Middle Eastern flows and strengthens leverage in price negotiations with other suppliers. If China normalizes Arctic LNG 2 purchases, discounted Russian volumes could displace some Atlantic basin LNG that China would otherwise take, loosening supply elsewhere and subtly reshaping spot trade flows. Nevertheless, wider uptake remains uncertain.

India, often floated as a next buyer, declared in 2024 that it would not purchase Arctic LNG 2 cargoes, due to sanctions exposure, though market signals have been mixed since. Ultimately, this first Chinese receipt turns Arctic LNG 2 from a stranded asset into a potential geopolitical instrument. Whether this ambition will materialize further hinges on secondary sanctions enforcement, the availability of suitable all-season carriers, and China’s calculations on balancing energy security with sanctions risk. Nevertheless, Arctic LNG 2’s outlook remains negative for now: the project is not fully operational, and its potential supply to China is unlikely to exceed 1% of the country’s LNG demand.

In December 2025, The Wall Street Journal reported on one key element of the Trump administration’s worries: "China’s Push to Master the Arctic Opens an Alarming Shortcut to U.S. " (https://www.wsj.com/world/china-arctic-military-submarines-b4e988b9). The new commercial arrangements with Finland aim to counter growing Russian and Chinese influence in the Arctic while boosting U.S. maritime capabilities.

On Sept. 3, 2025, two Chinese research vessels entered the U.S. Extended Continental Shelf (ECS) off Alaska, prompting the U.S. Coast Guard to deploy the icebreaker Healy to monitor their activities. On Aug. 31, the vessel Zhong Shan Da Xue Ji Di operated 230 nautical miles north of Utqiagvik, Alaska, followed on Sept. 2 by the icebreaking research vessel Jidi, located 265 mi northwest of Utqiagvik. To assist in monitoring the vessels, the U.S. Coast Guard also deployed an HC-130J Hercules aircraft from its Kodiak Air Station.

By dispatching research vessels into the U.S, ECS north of Alaska, China is testing both legal thresholds and U.S. capacity in the Arctic. Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), coastal states exercise sovereign rights over the continental shelf—including its extension beyond 200 nautical miles—and marine scientific research on the ECS requires consent from the coastal state. Although the U.S. has not ratified UNCLOS, it claims ECS rights as customary international law and has identified such areas in seven regions off its coast, including the Arctic.

To sharpen its legal position, the U.S. also published geographical coordinates for much of its ECS. China formally frames its Arctic presence through its 2018 white paper and its related Polar Silk Road ambitions, emphasizing scientific research and participation in Arctic matters under international law, as it seeks to build a year-round regional presence. The current deployment involves a broader Chinese fleet of five vessels operating in the Arctic this season, suggesting a coordinated campaign of oceanographic data collection with potential strategic utility, even as China publicly underscores scientific aims. From an operational perspective, this incident spotlights persistent U.S. resource gaps: the U.S. Coast Guard remains the country’s only routine surface presence in the region and faces notable shortcomings in ice-capable assets and Arctic infrastructure. While plans for Polar Security Cutters are advancing, capability lags and competing demand for cutters constrain persistent surveillance and at-sea enforcement in the region.

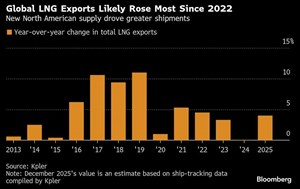

At the close of 2025, Bloomberg Intelligence (https://www.bloomberg.com/professional/insights/commodities/global-lng-market-outlook-2030/ ) released their forecast for continued expansion in global LNG trading volumes, with growth rates of 7.5% to 8% anticipated for 2026. KPLER's report on this, as released in December of 2025, was even more definitive (https://www.kpler.com/product/commodities/lng-insight-and-s-d ), Fig. 6.

A DIFFERENT ANGLE ON ARCTIC GEOPOLITICS AND TRANSIT

For a different perspective, we consulted with Dr. Troy Bouffard, U.S. Army (ret.), who directs the Center for Arctic Security and Resilience at the University of Alaska-Fairbanks. He’s also a research fellow at West Point’s Modern War Institute and adjunct professor at the U.S. Army War College. He formerly served as a congressional fellow and Arctic advisor with the U.S. Senate.

His view, shared exclusively with World Oil, is that “the U.S. is signaling Arctic opportunities with a clear tilt toward oil and gas by fast-tracking LNG, invoking energy emergency powers, and standing up a pro-fossil coordination council, while simultaneously throwing new policy barriers at wind and solar. Alaska is still courting LNG in the Far North by leveraging partnerships and advancing regulatory steps, but firm capital is not yet in place.”

His view is that current MOUs/HOAs (Heads of Agreement) remain non-binding when bankable SPAs are still needed to unlock lenders and move to FID. “In the next 12 months, I expect some issues toward progress, as IEA has indicated that a global surge in LNG demand will occur [during] mid-2026, with expected oversupply starting by 2029, leaving Alaskan LNG development in a timing predicament, along with the continuing pressure of infrastructure, as well as effective export volume solutions and geographically limited client options.”

Bouffard tracks policy and market signals that he thinks are steering investment toward Norway’s Barents assets, as the sanctioned Russian Arctic remains decoupled from Europe. “Stable Norwegian fiscal terms and annual APA licensing sustain exploration/appraisal, while Johan Castberg oil and Snøhvit/Hammerfest LNG anchor near-term supply,” says Bouffard. “EU restrictions on Russian LNG/trans-shipment and rising carbon/compliance costs (EU ETS, methane rules) further benefit sanction-safe Norwegian hydrocarbon options. Platform electrification and emissions abatement are becoming license ‘table stakes,’ but they also prolong asset life by preserving offtake options into Europe. The Arctic net effect is that lenders and operators view Barents oil and Norwegian gas as the bankable Arctic hydrocarbons for Europe over the medium term, as Oslo continues to lead supply growth to meet demand during European winters previously provided by Moscow.”

During 2025, Russia set a new Northern Sea Route (NSR) cargo record of ~37.9–38 Mt in 2024, with Rosatom projecting similar volumes for 2025. Bouffard tracks the flows, and he says that “LNG activity stayed robust, where Yamal LNG logged a record 287 voyages from Sabetta, Russia, in 2024, and Arctic LNG 2 finally began sending China-bound cargoes via Kamchatka trans-shipment during August–September 2025.

On crude, Russia resumed Arctic-route oil liftings during the 2025 season, often using sanctioned tankers. Fleet capacity is inching forward, as the first Russian-built ARC7 LNG carrier enters service in the second half of 2025. This is easing, but not eliminating, the tanker bottleneck. In the next 12 months, Russian Arctic hydrocarbons should keep moving east, with LNG volumes dictated by Arc7 availability and ice seasons and crude, depending on STS workarounds.” Rising sanctions/insurance premiums will continue to cap growth and provide improvements on global benchmarks.

Bouffard tracks the Chinese role. “During 2025, China quietly deepened its Arctic energy role by absorbing the first sanctioned Arctic LNG 2 cargoes, including several routed via Kamchatka to China’s Beihai terminal and leveraging its 20% equity (CNPC/CNOOC) to keep the project commercially alive despite Western efforts. In the next year, China will remain the primary sink for sanctioned Russian Arctic gas over the next year, taking a trickle of Arctic LNG-2 cargoes routed via Murmansk/Kamchatka, with deliveries constrained by Arc7 carrier availability and winter ice. Beijing and Moscow will keep nudging yuan-settled trades and east-facing logistics, further decoupling these flows from EU ports. Power of Siberia-2 will generate headlines but no near-term supply. Terms will likely remain unresolved, and impacts are on pace for the 2030s. China’s CNPC/CNOOC stakes anchor commercial alignment, while interest in the NSR may grow at the margins without a broader shift, given insurance, environmental and infrastructure limits.”

BAKER HUGHES’ TAKE ON THE ARCTIC

Exclusively for this Regional Report, Baker Hughes shared their Arctic assessment with World Oil. “Alaska’s upstream oil and gas industry is at a critical turning point,” said the firm. “Historically defined by vast reserves and operational challenges, the region is now shifting toward leaner, more agile models. Operators are prioritizing capital discipline and efficiency to sustain production amid volatile prices, creating opportunities for oilfield service companies to move beyond transactional roles and become strategic partners in integration and performance accountability.

“Service providers, in turn, are rethinking how they create and capture value. Models, such as integrated services, are gaining traction as part of their growth strategies. For example, approaches like Baker Hughes’ Mature Asset Solutions are being adapted to Alaska’s unique context—targeting aging North Slope fields and leveraging advanced drilling, enhanced recovery, and digital technologies to extend the economic life of assets once considered mature. In the same path, operators are utilizing innovative artificial lift technologies, including rig-less ESP systems to optimize reservoir recovery while reducing intervention costs and minimizing deferred production. The approach is particularly advantageous in remote environments like Alaska, where logistical constraints and high rig mobilization costs make conventional ESP interventions challenging.

“At the same time, operators are focusing on extended horizontal well designs as a core strategy to unlock maximum asset value. These are being achieved through the implementation of digital solutions and automation technologies that improve performance and wellbore placement in complex drilling environments. Additionally, automated field production solutions are being used to optimize pump, well, and field-level performance, contributing to improved operational safety, efficiency, and sustainability. By integrating disciplines and deploying tailored recovery solutions at scale, these initiatives are redefining what is technically and commercially recoverable in harsh Arctic conditions.

“Meanwhile, the Alaska LNG Project has the potential to be one of the most significant energy infrastructure projects in U.S. history. The project includes an 807-mi, 42-in. pipeline from Prudhoe Bay to a liquefaction terminal in Nikiski, targeting up to 20 million metric tons per annum (MTPA) of LNG production. The project emphasizes ESG compliance through carbon capture and reinjection, and has attracted global interest exceeding $115 billion, with Baker Hughes being one of the major technology partners. Once operational, Alaska LNG will provide affordable domestic energy, strengthen U.S. energy security, and position Alaska as a competitive supplier in the global LNG market. This creates opportunities for innovative collaboration between operators and service companies with full-spectrum upstream capabilities.

“This dynamic marks a pivotal inflection point for Alaska’s upstream industry. Service companies are no longer just enablers; they are emerging as co-stewards of production. Both operators and service providers appear closer than ever to aligning on a new definition of how value, risk and accountability are shared across the entire field life cycle.

In the background of the new Arctic dynamics there are some fast-changing realities, and we must especially consider the fact that the global LNG market is experiencing significant growth. Last year saw the largest export jump in three years (approximately 4%). There are three key growth factors behind this:

- New capacity. Major projects in the U.S. (Plaquemines) and Canada (LNG Canada) are ramping up, adding significant export capacity.

- Asian demand. China continues to lead import growth, with South & Southeast Asia also key,

- European security. The surge helps Europe diversify away from Russian gas, boosting overall demand.

(Sidebar): Another view of the Arctic environment

To better assess the Arctic’s precarious environmental dynamic, we talked with Elena Tracy, senior advisor on Sustainable Development at the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) Global Arctic Programme. She points out that the Arctic has long been regarded as one of the last nature refuges of global significance because it has been largely spared, up until now, from the harmful impacts of resource extraction: “However, in the last couple of decades, there has been growth in the extraction of mineral resources including oil and gas. Three countries are currently producing hydrocarbons above the Arctic Circle – Russia, the U.S. and Norway—with Russia leading, by far, in terms of production volumes.“

WWF and other global organizations are especially concerned about Russia, which “has been, by far, the largest contributor, responsible for more than 90% of the oil and gas production above the circle, with the majority of currently producing fields located in the Barents Sea and Kara Sea basins.” Alaska in the U.S. comes second in terms of its Arctic production volumes, producing oil on the North Slope; “whereas Norway is third, when measured by Arctic volumes, although its share is now comparable to Alaska’s. This is since Norway increased offshore oil production in March 2025, with the opening of Johan Castberg field in the Barents Sea”—the world’s northernmost active offshore oil field (74.50° N).

WWF and their allies worry that governments of these countries continue to issue new exploration licenses “for Arctic frontier and ecologically sensitive areas that were previously considered unfit or uneconomical for fossil fuel projects. In the foreseeable future, the U.S. may become the biggest Arctic offshore producer of oil and gas, if the government implements its proposed five-year program aimed at dramatically expanding offshore oil and gas leasing in federal waters,” including offshore Alaska areas.

Related Articles- What's new in exploration: A fresh look at Venezuela with the benefit of hindsight (January)

- Orphaned wells remain a problem (December 2025)

- Keeping the Gulf of America as our energy anchor (December 2025)

- Energy services: The relentless backbone of global energy security (December 2025)

- “Drill, Baby, Drill”— Hmmm…? (December 2025)

- This time….it will still be the same (December 2025)

- Subsea technology- Corrosion monitoring: From failure to success (February 2024)

- Applying ultra-deep LWD resistivity technology successfully in a SAGD operation (May 2019)

- Adoption of wireless intelligent completions advances (May 2019)

- Majors double down as takeaway crunch eases (April 2019)

- What’s new in well logging and formation evaluation (April 2019)

- Qualification of a 20,000-psi subsea BOP: A collaborative approach (February 2019)