What's new in exploration

Oil field service companies have been walking upstream employees out the door at a consistent rate since October 2015. I also know some non-oil magazines are bragging that HR is a demand career for U.S. businesses. The two events cannot be the result of overregulation, or King Hubbard predictions. It appears to be a result of poor confidence in/by senior management of current issues. I successfully ran a highly-technical global business with an outstanding executive secretary, a travel agent and five exceptional employees mentoring 300 less experienced people. We brought in an HR expert, because corporate required us to respond to a Wall Street demand about our direction. Changes were made, and not long after, the company elected to divest into FPSOs. Our costs went up, and the company was forced to file for bankruptcy two years later. Weren’t we smart?

Business schools teach their students to start solving problems by laying-off employees in excess, starting with the bloat from the bottom of the employment pile. Shareholders react positively by pushing stock prices up a few points. Then, senior management gets their bonuses. However, shareholders will not continue to invest in a company, if executive management kills off its core business. We have been living near that cliff’s edge for years, starting when we outsourced our technical skills, corporate books, and IT functions. The result is a stereotypical corporate footprint, where it is difficult to introduce new exploration technology.

I am told that today’s oil companies are striving for $15/bbl production opex cost, and some are actually getting there. The biggest competitor to my former small producing company was a group from East Texas, who waterflooded the Frio and then stripped oil. They do not use petrophysical logs or know how to spell “seismic,” but they make money on 3% oil cut per 1,000 bbl of water. Do we want to end up like that in shale oil? However, it is unlikely the EPA will allow such operational nonsense. Robots and replacement hires will not solve the missing-talent issues. The most valuable exploration tool is an experienced human, who has drilled successful wells and also knows why some were dry holes.

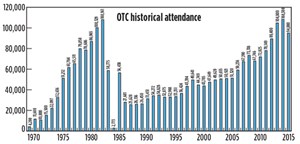

What’s not new in exploration. Hysteresis is not just a physics term. It also, explains the lag in recovery time needed to get back to whatever was before, or a new normal. When you compare attendance at this year’s Offshore Technology Conference (OTC) in Houston with the similarly trending price of oil, the U.S. rig count, the total offshore rig count, or college petroleum-focused enrollment, it is obvious that the fall-off is much more rapid than the recovery: http://www.otcnet.org/Content/History-of-OTC/3_6/

RULE: The longer the downturn, the longer the recovery. Consider the incredible amount of time that it took to recover from the 1984-1986 bust cycle!

Every industry down-cycle has caused talent depletion, and a slowdown in college replacements when the upturn occurs. The longer the downturn, the longer it takes for talent recovery, no matter what new technology or method might appear. Three-dimensional seismic, workstations, color displays and horizon auto-picking that appeared after 1987 did not replace experience, or depth-of-training. Neither did AVO in 1988 or wide azimuth in 2010. Tally the dry hole cost after each mini or major downturn, and making that measurement, in my opinion, cost more than keeping experienced people on the payroll through the downturn in the first place. A much bigger cost is the loss of generational knowledge created by a work environment void of mentorship and transfer of experience.

So, reality says that operators and service companies could not afford to keep a majority of employees. Ok, this is a strong truism for service, but not so much for MOCs, IOCs and certainly not for NOCs. When oil was at or near $100/bbl for years, what did the operators do with the abundance? Most wasted the margins on gross inefficiencies. In today’s environment, optimized processes are proving daily, that such inefficiencies were never needed. The margins did not go to shareholders unless you consider 1% or 2% of share price a worthwhile dividend. Little investment went to new exploration. Most of the program went toward building out first-round reserves known since 2009.

This is not your grandparent’s downturn, or your dad’s. I suggest strongly that a significant percent of the net talent be retained, right now, for protecting and growing tomorrow’s workforce and for seeding new exploration. To do otherwise, will flatten the recovery line out to 2020 or beyond.

Of course, in the meantime, “we” will be a market opportunity for Wall Street. Rig count numbers, the lowest in over 60 years, say this one could be the worst downturn since reasonably accurate numbers could be compiled in the early 1900s. Most oil companies have not kept enough talent to learn why they succeeded, and fewer yet are brave enough to learn from their mistakes. How many internal dry-hole postmortem must we see in the oil patch before we change our attitude toward our most valuable resource? ![]()

- Applying ultra-deep LWD resistivity technology successfully in a SAGD operation (May 2019)

- Adoption of wireless intelligent completions advances (May 2019)

- Majors double down as takeaway crunch eases (April 2019)

- What’s new in well logging and formation evaluation (April 2019)

- Qualification of a 20,000-psi subsea BOP: A collaborative approach (February 2019)

- ConocoPhillips’ Greg Leveille sees rapid trajectory of technical advancement continuing (February 2019)