LNG markets continue to diversify and innovate

LNG usage in Asia continues to climb, while demand in Europe flattens. Traditional exporters in Africa and the Middle East are bracing for the start-up of U.S. LNG exports.

DAVID WOOD, DWA Energy Limited, Lincoln, UK.

In addition to planning and political wrangling surrounding proposed North American LNG export projects, which have received much media attention of late, this year has witnessed significant LNG market developments across the world. This report focuses on those developments, while placing North American export aspirations in the context of a growing, diversifying, global LNG market. AFRICA The highlight in recent months in Africa was the much-delayed, over-budget export of the first LNG cargo from Angola’s LNG facility at Soyo, Fig. 1. Thus, Angola became the 19th country to export LNG it had produced, the first since Peru in 2010. The technical problems, that delayed start-up of the $10-billion facility by about a year, mean that the operator, Chevron, will be watched closely for both plant reliability and the destinations of the export cargoes. The first cargo was delivered to Petrobras in Brazil.

Nigeria LNG (NLNG), Africa’s biggest LNG exporter, has been dogged by interruptions and force majeure incidents in 2013, bringing further into question Nigeria’s reliability as a gas supplier. In July, NLNG agreed to pay $140 million in disputed levies to the country’s maritime agency to end a three-week blockade of shipments from its export terminal, which cost the company some $500 million in lost cargoes. Other proposed Nigerian liquefaction projects awaiting development remain in limbo, anticipating the tax implications for gas producers and LNG exporters from the Petroleum Industry Bill yet to be ratified. The bill has been under discussion by the Nigerian legislature since 2009. New liquefaction trains at Arzew and Skikda in Algeria remain under construction. They are expected to enter production within the next year or so. Civil unrest in North Africa continues to impact LNG exports, particularly from Egypt. As of July, Egyptian production was severely curtailed (i.e., Damietta plant shut in, and Idku producing at about 25% of capacity). In a bilateral diplomatic deal with Egypt, Qatar agreed to provide five LNG cargoes between July and September, to replace LNG export cargoes from Egypt, so that gas can be redirected to supply domestic Egyptian gas demand. Although Africa’s involvement in the LNG industry is primarily focused on exports, PetroSA announced plans to build a 1.2-Mtpa, $510-million LNG receiving terminal at Mossel Bay, South Africa. A final investment decision on that project, for start-up in 2018, is expected in late 2014. AUSTRALIA Cost and schedule overruns continue to dog the Australian liquefaction plants under construction. For example, at the Chevron-operated Gorgon project on the North West Shelf (NWS), due onstream in 2015, cost estimates have risen in 2013 by $9 billion, or more than 20%, to $52 billion, due primarily to rising labor costs. Analyst reports suggest that the Ichthys project, with its liquefaction facility in Darwin, could end up with a capital cost in excess of $44 billion (some 30% above the project-sanctioned budget), or about $3,800 per metric ton of LNG produced, due to a shortage of skilled labor and high infrastructure costs for new undeveloped fields.

The three Curtis Island gas liquefaction plants being built in Queensland (Fig. 2), and associated with separate coal-seam gas-to-LNG projects, also continue to struggle with their budgets; schedules; tougher regulations with respect to produced water; and community opposition to fracing and surface footprints of gas production sites. Nevertheless, considerable duplication of effort seems to have occurred in relation to these projects (e.g. three separate pipelines delivering feed gas to Curtis Island). CNOOC, in May, increased its interest in BG’s Queensland Curtis LNG (QCLNG) train 1 project, and upstream assets, for $1.93 billion, and agreed to buy an additional 5 Mtpa of LNG from that project. Bechtel is constructing the three liquefaction facilities on Curtis Island. In August, the firm said that it was employing 9,500 people at these sites. Floating liquefaction solutions continue to gain favor for remote, offshore, NWS gas developments. Shell continues to make progress with its Prelude project, as Samsung started construction of the vessel late in 2012. In March, ExxonMobil and BHP Billiton announced plans to cooperate to build the world’s largest FLNG vessel (i.e. 7-Mtpa capacity, about twice the size of the Prelude vessel) to develop the NWS Scarborough field. Woodside shelved an onshore liquefaction plant development plan for its Browse project in April, only to re-launch an FLNG plan for the project in cooperation with Shell. This has placed the Australian federal government at odds with the Western Australian state government, which has long been pushing for an onshore liquefaction facility at James Price Point for the Browse project. PTTEP of Thailand is still some way from a final investment decision (FID) for its FLNG plan to develop Cash and Maple gas fields in the Timor Sea. GdfSuez and Santos announced a pre-FEED study commencing for their Bonaparte FLNG project in the Timor Sea, leading toward FID in 2014. ASIA High demand and prices for LNG mean that large amounts of LNG development activity continue across Asia. Malaysia has moved forward with FLNG, liquefaction and regasification projects in recent months. In May, Petronas commissioned its Melaka LNG receiving terminal with a cargo from Nigeria, Fig. 3. This terminal consists of two floating storage units (FSUs) converted from two old LNG carriers owned by Petronas. Each has a capacity of 130,000 cu m, and they are moored in a tandem arrangement, adjacent to a jetty.

Petronas awarded an EPC contract, worth about $2 billion, to JGC early in 2013 for construction of the 3.6-Mtpa train 9 at the Bintulu liquefaction plant, due to start up in late 2015. Daewoo and Technip began construction in June on the hull of Petronas’ first FLNG vessel to be located over Malaysia's Kanowit gas field, 180 km offshore Sarawak. The facility will be able to produce 1.2 Mtpa of LNG. With a commissioning scheduled for 2015, it should become the world’s first operational FLNG vessel. Petronas has already awarded a FEED study contract for a second 1.5-Mtpa FLNG vessel, to be located offshore Sabah, marking a clear strategy for developing small-to-mid-sized, remote offshore gas fields.

The Singapore LNG (SLNG) terminal was commissioned in second-quarter 2013, with BG supplying 3 Mtpa, Fig. 4. SLNG is already considering plans to add a fourth tank to the $1.7-billion, Jurong Island plant and, with LNG cargo reloading capabilities, has aspirations to become Asia’s primary LNG trading hub for short-term cargoes. Meanwhile, Indonesia has continued negotiations with CNOOC, to increase the $2.4/MMbtu price paid by China for LNG from the BP-operated Tangguh LNG facility under a 25-year supply agreement signed in 2002. The Tangguh liquefaction plant produces some 7.6 Mtpa, with plans to add another 3.8 Mtpa by 2019, about 40% of which has been set aside for domestic use. Indonesia plans to build small-scale LNG receiving terminals (i.e., up to 1-Mtpa capacity) at strategic locations to reduce its dependence on diesel-fuelled power generation. Provisional agreements have been reached to convert the old, redundant Arun liquefaction plant into a 0.4-MMcfgd LNG receiving terminal in northern Sumatra. A FEED study is underway on the 2.5-Mtpa phase 1 of the large Abadi FLNG project in the deepwater Arafura Sea, near the Australian-Indonesian border. Recent equity deals concluded for this project leave operator Inpex (Japan) with 65%, and Shell with 35%. The project is unlikely to be online before 2019. Thailand's PTT LNG sanctioned plans to double the capacity of its existing 5-Mtpa LNG import terminal at a cost of about $700 million, despite current under-utilization of the Phase 1 facility opened in 2011. The Phase 2 capacity is scheduled for operations in 2017. Shell began a FEED study in July for an FSRU to be located offshore Batangas, which would become the first LNG facility in the Philippines, if ultimately sanctioned. The U.S. Pacific Island territory of Guam is conducting a feasibility study for LNG imports to generate power. In Papua New Guinea, the ExxonMobil-operated PNG LNG export project progresses toward scheduled completion in 2014, but has suffered a number of community-related disputes and strikes in 2013. ExxonMobil and InterOil also have discussed the development of Elk and Antelope fields as a possible expansion phase to the PNG LNG project. In eastern Russia, Gazprom sanctioned, in February, the Vladivostok liquefaction export project. This is planned to ultimately consist of three process trains, each, with a capacity of 5 Mtpa. The first process train is scheduled to be put onstream in 2018, with some gas coming from the offshore Sakhalin region. In a separate initiative, Rosneft and ExxonMobil announced plans in April for a $15-billion liquefaction export project, based around gas resources of Sakhalin-1, for first production in 2018. If, as expected, Gazprom’s monopoly on gas exports from Russia is removed, these two projects will compete directly for customers and financing, particularly from Japan. Japan imported a record amount of LNG in 2012, and continues to import LNG to replace much of its shut-in nuclear power capacity. However, it is keen to secure cheaper sources of natural gas and is, therefore, also a key customer and participant in some of the proposed North American LNG export projects. South Korea also continues to expand and diversify its LNG supplies. In May, the country sanctioned a new 3-Mpta, $700-million LNG receiving terminal at Boryeong some 120 miles southwest of Soeul to be completed by the end of 2016. China continues to expand its LNG capacity, but the lack of a liberalized domestic gas market, and the low price of coal, are slowing down the uptake of LNG in many regions. China’s LNG import capacity is about 22 Mtpa, but with terminals under construction, this should increase to some 40 Mtpa by 2015. On the liquefaction side Technip was awarded an engineering contract in August to design and procure a 0.5-Mtpa plant in Shaanxi province. Work commenced to expand the Fujian receiving terminal by adding a fifth and sixth storage tank and four gas substations. In June, Shell entered a provisional agreement with Guanghui Energy to build a 0.6-Mtpa import terminal in Qidong, Jiangsu province, with a view to further expansion. That would be the first LNG import terminal in China not controlled by state-owned companies. CNOOC and GDF SUEZ concluded a five-year deal for the Cape Ann LNG carrier to be moored at Tianjin, beginning in October, to become the first FSRU project in China. EUROPE Due to prolonged economic recession, natural gas and energy demand generally remain in a trough. In addition, the significant price differential between European and Asian LNG prices means that fewer spot cargoes find their way into the European market. For instance, The UK LNG import terminals supplied just 8% of UK natural gas during the 2012/2013 winter, compared with 15% in the 2011/2012 winter, and 21% in the 2010/2011 winter. European power generators, however, continue to find that cheaper coal is available to displace pipeline gas and LNG. Consequently, more LNG has made its way to the higher-priced Asian markets. Several European utilities have renegotiated gas supply contracts with Russia and Norway to include more gas-hub-priced, and less oil-price-based, indexation. The EU's oil-indexed, long-term, gas supply contracts with Russia dropped below 20% in 2012. This means that more LNG and pipeline gas competition is occurring at the European hubs, in a market failing to grow in terms of throughput. Despite this tough market for LNG, significant activity has occurred in Europe, with respect to building and expanding import infrastructure and planning to do so. Poland plans to complete construction of its LNG terminal near Swinoujscie, close to the German border, by mid-2014. Polskie LNG, a subsidiary of Poland's state-owned natural gas pipeline operator, will operate the plant. The firm is already considering its expansion from 5 Bcm/year to 7.5 Bcm/year. In April, the Ukrainian state enterprise, LNG Terminal National Project, announced an agreement with Excelerate Energy, to provide a 5-Bcm/year FSRU to be located near Odessa in the Black Sea, and to be operational in 2014. The FSRU will serve as an interim facility while a 10-Bcm/year onshore facility is constructed, with a 2018 launch date and projected budget of $1 billion. Lithuania also has opted for an FSRU solution. While an equivalent onshore plant would have cost about $1 billion, Lithuania’s state-controlled oil terminal operator is reportedly leasing the ship, due to be delivered in 2014, from Hoegh LNG, in a 10-year deal for some $560 million. Securing the investment for this project remains a challenge, despite having secured a loan from European Investment Bank (EIB). Meanwhile, Finland and Estonia continue to seek a shared LNG import terminal, but have yet to agree on where it will be located. The eastern European and Baltic Sea projects outlined have a common objective–seeking independence from Russian gas, or at least, a more competitively priced source of gas. For similar reasons, Croatia’s state-owned gas transmission system operator, Plinacro, has completed this year, a concept design for a LNG receiving terminal on the Adriatic island of Krk. Russia, itself, has taken significant steps in 2013 to further expand its role in global LNG markets. In June, Gazprom announced plans to launch a 10-Mtpa, Baltic Sea liquefaction plant near St. Petersburg at the end of 2018. The only existing liquefaction export plant in Europe, Statoil’s Snohvit plant at Hammerfest (Norway), continues to suffer poor performance, with repeated operational shutdowns in 2013. It now seems certain that Gazprom will lose its current monopoly on exporting LNG from Russia, as the government has recently agreed in principle to allow Novatek and Rosneft to also export LNG. In April, Yamal LNG (80% Novatek; 20% Total; with CNPC of China in the process of concluding a deal with Novatek to acquire 20% equity in the project) awarded Technip and JGC the EPC contract to build the first 5.5-Mtpa liquefaction train by the end of 2016, with second and third trains to follow in 2017 and 2018. The opening of the Northeast Passage to Asia using ice class vessels (see shipping section) should improve the case for developing the Yamal project and other liquefaction projects in the Barents Sea. These projects will supply both Asian and European markets with relatively short supply routes. Norway and Sweden continue to cooperate on, and develop, a small-scale LNG industry along their coastlines. Following the 2011 commissioning of a 0.3-Mtpa liquefaction plant at Risavika near Stavanger by Skangass, it sanctioned Linde in late 2012 to build a 30,000-cu-m LNG receiving terminal, north of Gothenburg. This follows the completion of a 20,000-m3 terminal at Nynashamn in 2011.

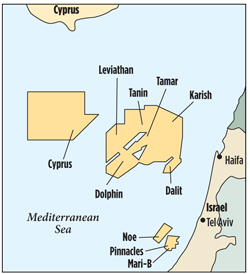

In August, the FSRU Toscana, a carrier converted in a Dubai dry-dock, arrived in Italy, offshore Livorno, Fig. 5. The facility has a 135,000-m3 capacity, with an annual regasification capacity of 3.75 Bcm. It is operated by OLT, a venture involving E.On, Iren and Golar. Elsewhere in the Mediterranean, gas liquefaction development planning has advanced for the large Aphrodite gas field in deepwater Block 12, offshore Cyprus, struck by Nobel Energy and its partners in 2011. Although this has inflamed political tensions between Cyprus, Greece and Turkey, and has been hindered by the recent $13-billion financial bailout of Cyprus by the EU, a three-to-five-train liquefaction plant in Vassilikos, to begin exports in 2020, is under discussion. It is attracting the attention of several major companies. Such a project also has the potential to tie in gas from some of Israel’s recent large finds (e.g. Leviathan field), but regional geopolitics will play a key role in deciding whether a LNG export collaboration project of that kind between Cyprus and Israel can be achieved within a reasonable time frame. LATIN AMERICA LNG markets in Latin America continue to grow, albeit on a minor scale, compared to other regional LNG import markets. Petrobras is expecting to import some 60 cargoes of LNG in 2013 to supply peak-load, gas-fired power plants in Brazil. By developing a number of small-scale floating receiving terminals, Brazil could become an LNG hub for Latin America in the future. The exact volumes depend upon hydropower availability. Meanwhile, Argentina struggled to secure the LNG cargoes it required in 2013. On the other hand, Chile succeeded in bringing the cost of its LNG closer to Henry-Hub-indexed prices. Cheniere Energy announced in June that it had taken a 50% stake in the Octopus LNG project, a planned regasification terminal near the southern Chilean city of Concepcion. This should help further to establish Henry-Hub-price indexation for Chile’s LNG imports. Mexico was obliged in 2013 to increase its LNG imports, paying prices that are several times higher than the Henry Hub benchmark. The country is failing to capitalize on the North American shale gas boom, because of a lack of available gas pipeline capacity. LNG exports from the U.S. and Canada, in the future, should change this situation. In June, it was announced that YPF (Argentina) would join PdVSA (Venezuela) and Chevron in developing LNG exports from the large gas resources discovered in the Plataforma Deltana region, offshore eastern Venezuela. Despite more than two decades of expressed intention to do so, Venezuela still has yet to commence construction of a gas liquefaction plant. Nevertheless, an LNG supply chain from Venezuela to Argentina, via Brazil, should be commercially viable. Uruguay is set to become the latest entrant into the Latin American LNG market. The government awarded a contract, in May, to GDF Suez, to build and operate an LNG receiving terminal in Montevideo, at an estimated cost of $1.125 billion. The plant will have a processing capacity of some 350 MMcfgd. The plant should be operational by first-quarter 2015, and receive some eight LNG cargoes per year. The facility should reduce Uruguay’s dependence on costly oil imports, and open opportunities for it to trade LNG and/or gas into the Argentine market. MIDDLE EAST Rather than LNG exports, which continue in large volumes, it is LNG import projects that have drawn the most attention recently. Emirates LNG plans to build a 9-Mtpa, LNG import terminal in Fujairah (UAE), including a floating storage and regasification unit (FSRU) integral to Phase 1 (4.5-Mtpa capacity) of the project. The first phase should be operational by 2015 and cost some $600 million. Meanwhile, Golar executed a firm, 10-year FSRU time charter agreement with Jordan in July. The FSRU Golar Eskimo will be moored off the Red Sea port of Aqaba. The vessel, to commence operations in 2015, is capable of storing 160,000 m3 of LNG and delivering up to 500 MMcfgd, with a peaking capacity of 750 MMcfgd. In August, Golar also announced that it had executed a firm five-year contract with KNPC of Kuwait, to provide an FSRU to support ongoing LNG import operations at Mina Al Ahmadi. The 170,000-m3, newbuild FSRU, Golar Igloo, will be delivered in late 2013 for service beginning in March 2014. The FSRU will only be required in Kuwait for nine months per year. For the three winter months, it will be free to engage in other spot cargo operations.

BP began delivering LNG to Israel via an offshore buoy, in January, as an interim measure until Tamar offshore field’s (Fig. 6) gas production ramped up, following the commissioning of the platform in April. The presence of the LNG import buoy is designed to offer Israel gas import security in the medium term. Gazprom announced, in February, a 20-year deal to sell at least a portion of LNG to be produced from planned FLNG facilities at Tamar. How much gas will be reserved for domestic supply remains to be clarified by governmental rulings. Another giant, deepwater, gas field discovery offshore Israel, Leviathan, has also been the subject of transactions (i.e., Woodside entering a provisional agreement to acquire a 30% interest) and uncertainty regarding export development plans (i.e., LNG or pipeline to Turkey), as well as quantities available for export. NORTH AMERICA In August, the U.S. DOE authorized exports of 2 Bcfgd from the Lake Charles LNG project in Louisiana to non-FTA (Free Trade Agreement) countries, such as Japan. This was the third such project to receive approval, despite a long list of other projects waiting for more than one year for approval, to sanction investments. The other terminals that have won non-FTA approval from DOE are Cheniere's Sabine Pass (Fig. 7) in Louisiana and Freeport's terminal in Texas. The three approved projects amount to some 5.6 Bcfd of capacity. The issue of how much LNG should be exported from the U.S. has fuelled a highly politicized, contentious debate. Some industry players, such as petrochemical companies, are arguing for strict limits to keep gas prices in the U.S. low, whereas oil and gas companies are asking for permission for large export volumes, to satisfy the large Asian and European demand for gas indexed to Henry Hub prices, rather than oil prices.

In Canada, six projects involving major IOCs and NOCs have surfaced in the past year, to export shale gas from British Columbia. These projects involve pipelines across the Rockies, and large liquefaction plants (up to 24 Mtpa) on the coast, seeking to export gas to Asia. These projects continue to work through the permitting and regulatory process, with significant hurdles still to be resolved. In February, British Columbia proposed the imposition of a new tax on LNG exports, which has introduced fiscal uncertainty to these projects. This contrasts with the industry’s expectation for tax incentives. The fiscal burden, in conjunction with the high costs associated with building mountain-crossing feed-gas pipelines, large-capacity liquefaction plants and the necessary shipping fleet, suggest that the delivered price of LNG from these projects landed in Asia is going to require a significant price floor. British Columbia unveiled, in July, an action plan for this unprecedented LNG export project activity, highlighting the need for some 60,000 construction workers in 2016 and 2017, if all the projects are sanctioned. Similar issues, and a track record of fiscal instability, pose hurdles for a competing, base-load, LNG export project from Alaska’s North Slope via a liquefaction plant at Valdez. An LNG export proposal, unveiled in February, involves a 42-in. natural gas pipeline. It would run about 800 mi across Alaska, with five take-off points for in-state gas use, and was estimated to cost between $45 billion and $65 billion. The fiscal uncertainty surrounding these North American LNG export projects extends to the Lower-48 states. An East Coast Canada LNG export project proposal from Goldsboro, linked to a $12-billion west-to-east gas pipeline project, also surfaced recently. E.On, the German utility, has provisionally agreed to take 5 Mtpa of LNG, half of the proposed Goldsboro plant capacity from 2020. These projects, still in their very early stages, highlight the appetite for North American gas in Europe, as well as in Asia. LNG imports to most U.S. receiving terminals have dried up, but a number of cargoes have been delivered in 2013 to the Everett and Elba Island terminals, by GDF SUEZ and BG, respectively, as part of long-term import agreements. However, operations at the GDF SUEZ Neptune deepwater LNG port, offshore Gloucester, Mass., were officially suspended for five years, based on an inability to operate on a commercial basis in the prevailing U.S. gas market. One new area of the U.S. that is keen to attract LNG imports is Hawaii. It is in the process of planning an LNG import project to replace expensive liquid fuels, particularly for power generation. LNG TRUCK FUEL/SMALL-SCALE MARKETS The last year, or so, has seen great enthusiasm around the world for using LNG as a heavy road vehicle fuel. The faster refuelling time; the smaller and lighter fuel tanks; lower chassis weights; and higher energy density of LNG versus CNG; typically make LNG trucks more attractive for long-distance service than CNG. Depending on the relative price and taxation levels for natural gas transportation fuel versus diesel and gasoline road fuels, the payback times on the extra costs of LNG trucks is about two years. The trucking industry is keen on using LNG, but there is still a long way to go in most regions, in terms of building the necessary infrastructure (i.e. storage and refuelling stations) to support large and rapid uptake, Fig. 8. Engine manufacturers, such as Cummins, Volvo and Westport, are in the process of developing and rolling out new LNG-fuelled engines.

The European Commission announced in January a program of support for, and development of, unconventional energy sources, including gas-powered vehicle usage and building of LNG ports. The program involves the installation of LNG refuelling stations in all 139 maritime and inland ports on the Trans European Core Network (TEN) by 2025. Analysts recently predicted that LNG-fuelled trucks could rise ten-fold in China to 800,000 by 2020. Beijing Public Transportation Group announced plans to acquire 3,100 LNG vehicles during 2013, and ultimately to operate the world’s largest LNG bus fleet, with 5,600 units. A $362.5-million financing package was signed into law in May, in Alaska, to support a small-scale North Slope gas liquefaction system, and LNG truck distribution system, to supply Fairbanks (400 mi south) and rural Alaska. Initial volumes are expected to be small (about 9 Bcf/ year) and be delivered in 2015. However, the initiative will lay infrastructure to support a natural gas market, to ultimately displace high-cost liquid fuels currently used for space heating. Trucked LNG is expected to cost Fairbanks consumers about $15/MMbtu versus the $4/ gal (i.e. about $30/MMbtu) paid for fuel oil in 2013. PRICES/SPARK SPREADS Since 2008, there has been a dramatic divergence in regional gas prices. This has resulted from the combined effects of the North American shale gas boom, the European financial crisis and increase in hub-based pricing, and the Fukushima nuclear accident in Japan shutting down significant nuclear power capacity. This has meant that in the 2011-to-2013 period, monthly average prices in Asia, strongly influenced by Japan, have hovered in the $17-to-$21/MMbtu range, versus $9 to $12/MMbtu at the UK’s NBP and $2.5 to $4.5/MMbtu at the Henry Hub.

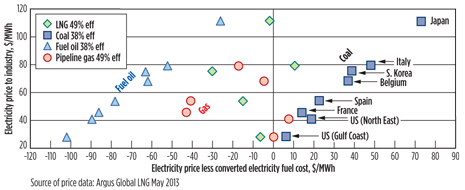

However, as a significant amount of LNG consumed globally is used for power generation, it is the spark spreads in LNG-consuming countries, compared to spreads for competing fuels, that highlight the competitiveness and sustainability of natural gas prices versus other fuels available to power utilities. In Fig. 9, it is clear that in 2013, coal is the most commercially viable fuel for power generators in the countries shown from all three regional markets. In contrast, fuel oil with large, negative, power-to-fuel price spreads is clearly uncompetitive. LNG and pipeline gas fall between these two extremes, but LNG only has a positive spark spread in two regions (Italy and the northeastern U.S). Across most of Europe and Asia, LNG is not a profitable proposition for power generators at prevailing gas and electricity prices. SHIPPING/LNG BUNKERING Whereas LNG shipping charter rates averaged close to $120,000/day in 2012, they have been down to around $100,000/day for short-term and long-term charters in 2013. This is due to the relatively static LNG supply situation, with delays in Angolan LNG cargoes, cutbacks in Egyptian exports, and interruptions to Nigerian supplies, all contributing to more vessels in the market than expected. Up to eight newbuild LNG vessel orders were placed by Chinese companies with three shipyards in China. Gazprom announced plans to build 13 new ice-class LNG carriers, featuring GTT containment technology and technical collaboration with South Korean shipyards. Meanwhile Yamal LNG awarded a tender to Daewoo, to build as many as 16 ARC7 tankers, designed for year-round transport of natural gas produced by the Yamal LNG project under development in northern Russia. The intention is to build (starting in 2017) at least some of these vessels in a new yard on Russia’s eastern coast. Gazprom also took delivery in 2013 of a second LNG carrier capable of sailing the Northern Sea Route (NSR). Russia’s long-term LNG strategy is to use the NSR for LNG deliveries to both Asia-Pacific countries and the European market. Shipping through the Arctic route can potentially save up to 20 days for Atlantic cargoes destined for Japan or South Korea. The expansion of the Panama Canal is due online in mid-2015. It remains set to have a significant impact on LNG shipping, particularly for future exports from the U.S. Gulf Coast to Asia. It will reduce the distance from the Gulf of Mexico to Japan by some 8,500 mi, and potentially save between 20 and 25 sailing days. It is likely that other Atlantic-Pacific LNG trades will also exploit the expanded canal. LNG as a marine vessel fuel, and plans for LNG bunkering facilities to support that, have gained significant momentum over the past year. Initiatives vary from dual-fuel (diesel and LNG) engines for large vessels to numerous ports seeking to provide LNG bunkering services. Shell has launched two LNG-powered Rhine barges. Tote Inc., which operates vessels serving Alaska and the Caribbean, signed a contract to build four large LNG-powered containerships in San Diego. Each vessel, powered by a MAN dual-fuel engine will be 764 ft long and 106 ft wide, with construction scheduled to start in early 2014, for delivery in 2015. CONCLUSIONS The LNG industry in 2013 continues to receive massive global investments while diversifying into new markets. The level of activity, from small-scale road fuel and marine bunkering applications to floating liquefaction and receiving terminals, highlight that there are many opportunities yet to be fully exploited. The industry is well-positioned to continue to attract investment and post growth for many years to come. However, it will have to overcome strong competition from coal in most regions, if it is to expand its market share in power generation significantly.

|

- Applying ultra-deep LWD resistivity technology successfully in a SAGD operation (May 2019)

- Adoption of wireless intelligent completions advances (May 2019)

- Majors double down as takeaway crunch eases (April 2019)

- What’s new in well logging and formation evaluation (April 2019)

- Qualification of a 20,000-psi subsea BOP: A collaborative approach (February 2019)

- ConocoPhillips’ Greg Leveille sees rapid trajectory of technical advancement continuing (February 2019)