|

Vol. 231 No. 10 |

|

|

HENRY TERRELL, CONTRIBUTING NEWS EDITOR

|

Oil in the water

On Sept. 19, the Macondo 252 well was officially proclaimed dead, following a successful pressure test on the relief well. It was exactly one day short of five months since control of the well was lost. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration estimated that 4.9 million bbl of crude oil was released during the event. Some of that (roughly 17%) was recovered directly from the well. The rest ended up in the Gulf of Mexico.

Crude oil in seawater is a phenomenon as old as the oceans. Hydrocarbons from oil seeps or other natural sources enter the marine ecosystem regularly, are broken down, eaten by microbes and, over time, made harmless. The Russian environmental chemist Stanislav Patin has compared accidental oil spills to intoxication of a living organism. In small amounts, the crude is easily metabolized. When millions of barrels go into the system over a short period, the natural defenses are overwhelmed, and the sea gets completely hammered.

What happens to oil in water? In a process that is not very well understood, the so-called “long-range hydrophobic force” causes oil particles in water to attract one another over what is, to a chemist, a long distance. In underwater blowouts, this is a good thing. The more oil clings to itself in large drops and dollops, the faster it rises through the water. (According to “Stoke’s Law,” a microdrop of oil 100 microns in diameter rises only 6 inches in 10 minutes.)

|

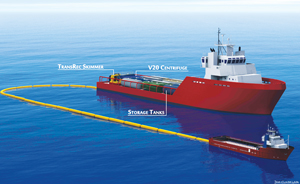

Artist’s rendering of the Ella G during skimming operations. The retrofitted platform supply vessel carries four V20 centrifuges. Courtesy of Ocean Therapy Solutions.

|

|

Within a short time after reaching the surface, oil spreads out into a slick, and degradation accelerates. Depending on various factors such as original viscosity of the oil, temperature and surface tension of the water, one metric ton (about 7.3 bbl) of crude can form a slick 50 m across and 10 mm thick in 10 minutes. As spreading continues over hours and days, much of the oil transforms into a gaseous phase. Volatile components evaporate, and soluble components are dissolved. When the slick reaches about 0.1 mm thick, it fragments and scatters with the wind and waves, and heavier fractions start lumping together. Storms and wave action can churn the remaining oil into a brown emulsion called “chocolate mousse.” This water-in-oil emulsion is very stable, and can persist in the environment for weeks. The so-called “reverse” emulsions (oil-in-water) are less stable and break down quickly.

From the bottom up. The best way to recover high-quality crude from a subsea blowout is to capture it at its source. In the Macondo well blowout, the improvised subsea containment dome was the first attempt at recovering the oil directly from the broken riser. Buildup of methane hydrate crystals made this unsuccessful. A second scheme involving an insertion tube to divert oil to a drillship produced better results. Some 22,000 bbl was collected this way. Later, a containment cap was installed directly on to the BOP stack, and the amount of crude recovered was increased daily, culminating in a reported one-day recovery of 22,000 bbl and flaring of 57 MMcf of gas. Methanol was injected at the wellhead to prevent hydrate formation (reducing the value of the oil somewhat). The flow was finally stopped when the “Top Hat No. 10” ram stack was installed and closed off.

Skimming off the top. What about the oil that isn’t captured directly, burned or dispersed and biodegraded? It either sinks, washes up somewhere or is removed.

According to BP, some 826,000 bbl of oil/water were skimmed from the Gulf and processed. Various technologies are used to skim oil, all are fairly old, and all involve corralling the oil with booms, then lifting it out of the water. “Weir” systems collect oil with floating separators that disrupt the interface where oil and water meet. Belt skimmers use bands of “oleophilic” material that oil clings to, and “drum” skimmers work similarily. All types work best when the oil/water interface is not disturbed, i.e., in good weather.

Separation complex. There have been more advances in the science of oil/water separation, and recent events have inspired further innovation. Traditional API oil/water separators consist of a channel that water passes through horizontally at a velocity that gives oil droplets time to rise to the surface to be skimmed. They are relatively inexpensive and low maintenance. These are used widely in oil refining, where there are large volumes to process, and lots of space.

More practical for use aboard ships are centrifugal oil-water separators. Simply put, these consist of a rotating cylindrical container. The heavier water accumulates at and is collected from the periphery of the container, while the lighter oil accumulates at the rotation axis. The most talked-about of these were developed by Ocean Therapy Solutions, the company owned by the actor Kevin Costner. Costner purchased the company from the US government in 1995, and has, along with team of engineers and scientists, spent 15 years and millions of dollars developing centrifugal separators. The largest of these, the V20, has a reported throughput of 200 gal/min., resulting in 99% oil stored and 99.9% pure water discharged. After testing, BP ordered 32 of devices.

Is skimmed oil valuable? The short answer is yes. Oil that is skimmed soon after reaching the surface is still relatively good once it is separated from the water. But, as we have seen, weathering takes its toll on crude, so once lighter fractions are gone, what’s left are heavy lumps that aren’t much good for anything. The aforementioned viscous “chocolate mousse” emulsion has to be broken down with chemicals before going through the multistage separation process.

It goes without saying, but it’s better if the sea doesn’t drink too much oil in the first place.

|