What's new in exploration

Lies, damn lies and harbor spies. (continued from Editorial comment) Within OPEC, the basing of production quotas, in part, on reserves resulted in overnight increases in the late '80s, most of which were unjustified. Worse, why should OPEC inform the world, in detail, of the status of their fields when it would serve only to reduce their income? For national oil companies, politics will always play a role, considering that jobs and careers are at stake. And for private firms, there is a long list of incentives to inflate reserves, such as stock valuations, a company's debt rating and the impact on financing exploration and proposed projects, terms in production-sharing contracts and compensation packages, to name a few. Mike Lynch was by far the most engaging speaker as well as the most convincing. He systematically debunked creaming curves, and emphasized that politics, contract terms, prices and costs have as much to do with discovery rates and production as does geology. He illustrated the sometimes bent logic of future prediction using cause-and-effect analogues by telling the following story. His daughter was sitting at a computer looking at overweight people with big bellies. She thought that they were pregnant and about to have babies, having incorrectly deduced that big bellies cause babies. Lynch said, “I couldn't tell her the truth, which is that babies come from drinking beer.” Finally – and this goes to the core of “peak science” – the peak itself is not fundamentally important. There is nothing in theory or in practice that precludes any shape of the world production curve, nor gives to it any importance whatsoever. Even Hubbert himself, who eventually came to believe that he knew the total world endowment and, thus, the area under his famous bell curve, originally said that he could not predict the shape of the curve. But that is a gross understatement. Given the normal uncertainties of future prices, discoveries (including elephant fields, inventions, breakthroughs, unknown energy processes/ sources), wars, growth, demand and government investment, the world production curve could have one peak, a peak-and-a half or a prolonged plateau. It is even possible to have a situation where oil production has peaked – not because of exhaustion of the resource – but due to a combination of prices, the growth rate of world economies and improving energy intensity, followed by an incredibly slow decline, as alternatives, perhaps even Power X, come online. Did anyone predict nuclear fission, or the relatively short time to fission-powered electrical generation? Put another way, it's possible, even likely, that serendipity will play the greatest role of all. There is an obvious analogy to the stock market here. Zillions of curves are generated to predict what the stock market will do. Like many others, you can try to use the past to predict future stock market trends, but don't be surprised if the market fools you. The folks who generate those curves make most of their money selling books, newsletters and editorial columns on what the stock market will do next, rather than on the market itself – that's where the smart money goes. The certainty that the future will resemble the past reminds me of the fellow who said, “If man was meant to fly, God would have given us wings.” The Wright brothers lifted off the next day. There's an old country saying, “If you don't know, just say so.” The simple fact is, no one knows what ultimate recoverable world reserves are, or will be, but if you wanted to cite history, it's a long history of “the end is near” followed by upward revision. There's a host of good reasons why the world – especially importers – should wean itself off oil. But certainty of impending doom is the lousiest reason of all. Tracking oil volumes. After his speech, Matt Simmons commented that he found recent clamor for transparency in natural gas supply and demand data ironic. “Compared to oil data, gas data is highly accurate,” he said, somewhat tongue-in-cheek. I asked him whether OPEC still had excess capacity, and whether the cartel could control prices. Although I considered the question a no-brainer, his answer was surprisingly vague and non-committal.

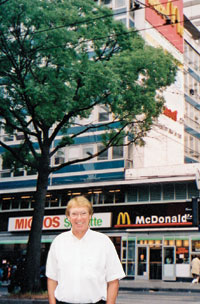

“If you want to know who really controls prices, it's a fellow who works above a grocery store in Geneva, Switzerland,” said Simmons. I had heard of this guy, and his company, but never paid it much attention since I wasn't in the trading business. Coincidentally, I was recently in Geneva, so I looked up the man whose business, Perto-logistics Ltd, helps determine world oil prices. Conrad Gerber does indeed work above a supermarket (as well as a McDonalds). He's a likable fellow from Rhodesia who has been tracking tanker traffic, oil or product type, and source and destination, since 1980. Gerber takes bills of lading, custody transfer numbers, tanker specs and how they sit in the water, and other information gathered by a network of harbor spies, if you will. I inferred from our discussion that, apparently, some of them truly are at risk, at least for their jobs, if not for their lives. Realistically, Gerber doesn't actually control prices, since his role is to try to accurately determine for his clients where much of the roughly 250 oil and 230 product tankers, comprising some 500 million barrels of oil, is at a given time. However, he admits that his data does affect world prices. I asked Mr. Gerber if he thought that oil supply would be adequate for the foreseeable future. He answered, “I certainly do.”

|

|||||||||||

- Prices and governmental policies combine to stymie Canadian upstream growth (February 2024)

- U.S. producing gas wells increase despite low prices (February 2024)

- U.S. drilling: More of the same expected (February 2024)

- U.S. oil and natural gas production hits record highs (February 2024)

- U.S. upstream muddles along, with an eye toward 2024 (September 2023)

- Canada's upstream soldiers on despite governmental interference (September 2023)

- Applying ultra-deep LWD resistivity technology successfully in a SAGD operation (May 2019)

- Adoption of wireless intelligent completions advances (May 2019)

- Majors double down as takeaway crunch eases (April 2019)

- What’s new in well logging and formation evaluation (April 2019)

- Qualification of a 20,000-psi subsea BOP: A collaborative approach (February 2019)

- ConocoPhillips’ Greg Leveille sees rapid trajectory of technical advancement continuing (February 2019)