Regional Report: The Arctic

Arctic exploration and development are moving forward; or backward; or standing still, depending on where you step into the circle. The challenge of profitably drilling a well above 66° 33 minutes north latitude is complicated by variables that range from reindeer habitat and the extent of sea ice to geopolitical maneuvering—not to mention geology.

While Russia builds huge icebreakers and makes grand plans, on the other side of the circle, Canada has effectively bowed out of the game. The U.S. on the other hand, is teeing up new rounds of Arctic leasing, as operators buy and sell assets, and environmentalists howl. Norway, meantime, is quietly drilling wells in the Barents Sea, while Iceland and Greenland hope ardently for suitors and production.

AROUND THE CIRCLE

Ice is the overarching context for Arctic development. It’s remote, frozen expanse has long been an impediment to development of all sorts; but now, as the ice sheet shrinks, access to the region grows and brings with it a multitude of worries and opportunities. There is a wide range of response from the various stakeholders.

In August, the ice extent averaged 1.94 million mi2—only 120,000 mi2 more than the record low observed in 2012, says the National Snow & Ice Data Center (NSIDC). In 2018, it was about 2.2 million mi2. The ice sheet typically reaches its minimum extent in September, Fig. 1.

RUSSIA

With a 7,000-mi Arctic coast, Russia has many area interests, including hydrocarbons. But its offshore Arctic exploration and development are greatly constrained by U.S. technology prohibitions, and efforts are focused largely on onshore assets.

That effort includes ambitious construction of fleets of icebreakers and tankers, and networks of pipelines to move output to market. The robust effort is mostly gas activity, driven by the need to maintain production, observes the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). Oil development is hindered by sanctions, while LNG is limited by the need for considerable state support.

In contrast, the United States has lower Arctic activity, due in part to politics and lack of a consensus on Arctic development, says CSIS. “But more fundamentally, U.S. energy companies have more options to produce oil and gas.” Until that changes, the U.S. is unlikely to match what Russia is doing in Arctic energy—or need to, says CSIS.

Russia’s Arctic activity includes Rosneft’s plans to establish a cluster of fields along the Northern Sea Route. The intent is to transport 80 million metric tons in freight volume by 2024. The project comprises the Vankorsky group of fields and prospects in South Taimyr. Its next stage includes mostly onshore assets in East Taimyr near Khatanga. First production is expected by 2024.

To develop Arctic assets, Rosneft, Rosneftgaz and Gazprombank plan to build a new shipyard on the east coast near Vladivostok. The Zvezda yard, in the shipbuilding center of Bolshoy Kamen, will featuring the largest drydock in Russia. It reportedly has orders for 26 vessels, including icebreakers and tankers.

In May 2019, Gazprom announced the discovery of two new fields on the Yamal shelf in the Kara Sea: Dinkov field, in the Rusanovsky licensed block, with estimated recoverable gas reserves of 390 Bcm, and Nyarmeyskoye field in the Nyarmeysky license, with estimated reserves of 121 Bcm, Fig. 2.

The Yamal Peninsula has 32 fields. The largest gas field is Bovanenkovskoye, with projected production of 140 Bcmg/year. The area also includes Kharasaveyskoye field, where development began this year and first gas production is slated for 2023. The field is mostly onshore but includes Kara Sea assets that will be drilled from shore.

Yamal LNG shipments in August reached 20 MMt since Train 1 started in December 2017. The August cargo was loaded on a new Arc7 ice-class tanker, the twelfth Arc7 ice-class tanker built specifically for the Yamal LNG project. There are now three liquefaction trains at Yamal LNG, with combined production capacity of 16.5 MMt per year.

UNITED STATES

The only state with territory inside the Arctic Circle, Alaska gets most of its oil production from diminishing North Slope operations. State oil production last year was 190 MMbbl (186 MMbbl from the North Slope; 4 MMbbl from Cook Inlet), compared to 193 MMbbl in 2017 and 759 MMbbl in 1988.

But there’s hope for a rally, with new production coming from federal prospects in the Beaufort Sea and Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR), and from state and Native properties. In these areas, lease sale activity, exploration and development activity, and some big changes in asset ownership are keeping Alaska in the game.

State and federal lease sales are warming up interest. Alaska plans another sale this fall, as part of a five-year plan ending in 2023. The Alaska Department of Natural Resources will offer area-wide leasing in the Beaufort Sea, North Slope and the North Slope Foothills, as well as three Special Alaska Lease Sale Areas (SALSA) offered last year (Gwydyr Bay, Harrison Bay, and Storms Blocks).

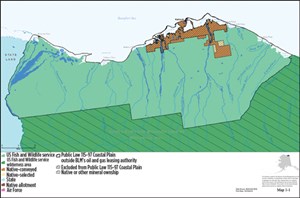

The ANWR sale mandated for this year by 2017 legislation is the first of two to be conducted by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), Fig. 3. First production may not happen until 2031, a horizon that allows for exploration, appraisal, permitting, and development, and, no protracted legal battles—which are already queuing up.

A Beaufort Sea 2019 lease sale is pending the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management’s (BOEM) finalization of its 2019-2024 National OCS Oil and Gas Leasing Draft Proposed Program. The draft plan provides for three OCS lease sales in Alaska’s Beaufort Sea through 2023, Fig. 4.

BP and Hilcorp. A big chunk of legacy real estate changed hands in late August, with the announced purchase of BP’s Alaska business by Houston-based Hilcorp for $5.6 billion. The sale ends almost 60 years of BP presence in Alaska. Hilcorp has been operating in Alaska since 2012 and was already the largest private oil and gas operator in the state, with more than 75,000-boed gross production. In 2014, the company had purchased BP interests in four operated North Slope oil fields.

The sale, to be completed in 2020, includes BP’s entire upstream and midstream business in the state, including BP Exploration (Alaska) Inc., which owns all of BP’s upstream oil and gas interests in Alaska, and BP Pipelines (Alaska) Inc.’s interest in the Trans Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS). The transaction underpins BP’s two-year, $10-billion divestment program.

BP says its net oil production from Alaska in 2019 is expected to average almost 74,000 bpd. The company operates Prudhoe Bay and holds non-operating interests in the Milne Point and Point Thomson producing fields. It also holds non-operated interests in the Liberty project and exploration lease interests in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR).

Hilcorp Alaska LLC is actively developing North Slope assets. Its Liberty Project oil and gas development and production plan, the first oil and gas production facility in federal waters off Alaska, was conditionally approved last year by BOEM. The development, said BOEM, would be the first oil and gas production facility in federal waters off Alaska.

The proposal is for a nine-acre artificial gravel island in the shallow waters of the Beaufort Sea, about 20 mi east of Prudhoe Bay and about 5 mi off the coast. The facility would be similar to the four existing artificial islands currently operating in the area’s state waters: Spy Island/Nikaitchuq field, (ENI), Northstar Island (Hilcorp), Endicott Island (Hilcorp) and Oooguruk Island (Caelus). Hilcorp anticipates peak production of more than 70,000 bopd and 20 to 30 years of field life.

The company lists four operations on the North Slope. East to west they are: Liberty, Duck Island Unit (an Endicott satellite drilling island), North Star Unit (off Prudhoe Bay) and the Milne Point Unit (adjacent to the Kuparuk River Unit).

In a 2018 North Slope outlook, Hilcorp’s Milne Point activity included a 17-well drilling program employing two rigs, and 20 workovers planned. Field development included Milne Moose Pad facilities and a pipeline, and a 15-MW power plant. The Moose Pad production came online during April 2019 and is the first new pad since 2002. The project will comprise 50 to 70 wells. Peak production of 16,000 bopd is expected in 2020, with estimated ultimate recovery of 30 MMbbl to 50 MMbbl of oil.

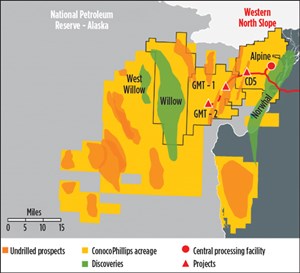

ConocoPhillips. Last year, ConocoPhillips made two big deals in the Arctic. It bought out Anadarko’s 22% interest in COP’s Western North Slope joint venture for $400 million, giving it full control of that asset. It also traded a 16.5% interest in Clair field of the UK North Sea for BP’s 39.2% interest in the Greater Kuparuk Area, as well as its 38% interest in the Kuparuk pipeline. Those deals boosted COP’s ownership in those assets to around 95%.

The company is Alaska’s largest crude oil producer and the largest owner of exploration leases, with approximately 1.3 million net undeveloped acres at the end of 2018. The company has an operated interest in the Alpine Field/Western North Slope assets, and in 2018 acquired additional interest in the area. In an August update, COP said it planned to advance GMT-2 area Willow and Narwhal appraisal drilling. The BLM in August opened the environmental impact statement plan for the Willow development for pubic comment.

Appraisal of the Greater Willow Area will evaluate horizontal well performance, determine lateral reservoir connectivity, and appraise West Willow. The Narwhal appraisal aims to verify recoverable volumes and evaluate well performance, Fig. 5.

Last year’s exploratory program drilled six wells on the Western North Slope, five in the National Petroleum Reserve–Alaska (NPRA) and one on state acreage. Four wells are in the Greater Willow Area. A seismic program was also conducted on state leases.

In July 2019, ConocoPhillips was deploying a new extended-reach drilling rig to work in its Fiord West field, northwest of the main Alpine field. The rig, said to be the largest mobile land rig in North America, was due to arrive in Deadhorse, Alaska, in November.

ENI last year acquired 124 exploration leases (for a total of approximately 350,000 acres) onshore in the North Slope’s Eastern Exploration Area (EEA) from Caelus Alaska Exploration Company. Eni will hold all the leases with a 100% working interest. The EEA is southeast of Prudhoe Bay field and about 20 miles from Deadhorse, so it is close to existing infrastructure, including the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System.

CANADA

The Arctic coastline comprises nearly 75% of Canada’s total 150,993 miles of shoreline, including the shores of 36,000 islands. The country’s 2016 five-year moratorium on all new oil and gas activity in Arctic waters has idled development, and efforts to extend the freeze are in full swing.

While the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP), points to lost opportunities, and market uncertainty, Northern Affairs Minister Dominic LeBlanc, and others insist the offshore ban is necessary to ensure development that protects the environmental and Indigenous people, and requires time to consult with people, government and industry.

Onshore, CAPP statistics for 2018 show no drilling activity in the territories and Arctic islands, and no production. Overall, capital investment across Canada’s oil and natural gas industry is forecast to fall to $37 billion in 2019, compared to $81 billion in 2014.

NORWAY

The Norwegian Petroleum Directorate suggests undiscovered oil and gas resources in the Barents Sea are twice as large as previously assumed. Undiscovered resources on the Norwegian Continental Shelf will likely play an important role in maintaining profitable petroleum activities, said the directorate.

Equinor and its partners in August announced a Triassic oil discovery in the Barents Sea. The Sputnik well confirms the presence of oil north of the 2013 Wisting discovery. Both wells are north of the 2013 Johan Casteberg field, slated for FPSO development. A decision on an onshore terminal for the field was expected this year. Equinor believes the field is key to further development and infrastructure in the Barents Sea, where the company is exploring four licenses, Fig. 6. Recent discoveries include Skruis (2018, Equinor), Filicudi (2017, Lundin Norway AS) in the Johan Casteberg area.

Most of the Barents Sea is considered a frontier petroleum province. The only fields in production are Snøhvit (Equinor) and Goliat (Var Energi AS), which came onstream in 2007 and 2016, respectively. Snøhvit gas is transported by pipeline to an LNG facility; Goliat production goes to an FPSO, and gas is reinjected.

DENMARK/GREENLAND

Denmark’s Arctic presence is via Greenland, an autonomous territory with no oil or gas production. Greenland has three major basins that the USGS says may hold 52 Bboe, but industry interest has been limited. Seismic work in 1989 investigated areas off the western coast, followed by several leasing rounds starting in 2002. Off the northwest coast, four leases in the Greenland Sea were awarded in 2013. There are currently 23 offshore licenses awarded by Greenland.

Onshore, Greenland officials last year told Reuters that they will offer blocks in 2021, reportedly on Disco Island and the Nuussuaq Peninsula on the west-central coast. Industry and Energy Minister Aqqalu Jerimiassen said Chinese firms CNPC and CNOOC have expressed interest. CNOOC recently returned licenses in Iceland’s offshore Dreki area.

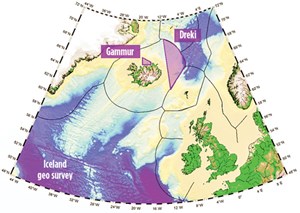

ICELAND

Iceland’s oil and gas exploration is, thus far, limited to geophysical data from academic, governmental and industry datasets. Licenses for exploration and production are handled by Orkustofnun, National Energy Authority. The two areas of interest on the Icelandic continental shelf are Dreki, to the east and northeast, and Gammur on the northern insular shelf. The complex geology is further confounded by volcanic activity that confuses seismic results, Fig. 7.

The Arctic Circle runs through both areas. Iceland’s only three licenses to explore the Dreki area were returned in 2017 and 2018, following 2D seismic work. No future licensing rounds are scheduled. The northernmost 30% of the Dreki area is subject to an agreement with Norway to participate in licenses up to a 25% share.

- Coiled tubing drilling’s role in the energy transition (March 2024)

- Advancing offshore decarbonization through electrification of FPSOs (March 2024)

- The reserves replacement dilemma: Can intelligent digital technologies fill the supply gap? (March 2024)

- What's new in production (February 2024)

- Subsea technology- Corrosion monitoring: From failure to success (February 2024)

- Digital tool kit enhances real-time decision-making to improve drilling efficiency and performance (February 2024)

- Applying ultra-deep LWD resistivity technology successfully in a SAGD operation (May 2019)

- Adoption of wireless intelligent completions advances (May 2019)

- Majors double down as takeaway crunch eases (April 2019)

- What’s new in well logging and formation evaluation (April 2019)

- Qualification of a 20,000-psi subsea BOP: A collaborative approach (February 2019)

- ConocoPhillips’ Greg Leveille sees rapid trajectory of technical advancement continuing (February 2019)