Is this just another cycle or an opportunity to change?

During 2014, oil prices plunged from more than $110/bbl for West Texas Intermediate (WTI). They finally bottomed out at just above $33/bbl in February 2016, Fig. 1. That is a $77-drop over a 20-month period. WTI remained below $60/bbl for a three-year period, from December 2014 through December 2017. This dramatic drop in oil prices over a sustained period caused a significant negative impact on the global upstream industry, generating massive layoffs of personnel, a halt in exploration, and a hiatus on production projects. The impact was felt in all areas of the industry, especially offshore projects.

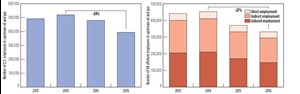

While there has been some benefit to the general public regarding energy costs, it has had a very harmful effect on the lives of the rank and file of the industry. In the U.S., alone, oil-and-gas job losses from 2014 through 2016 have been approximately 24%, or in the range of 100,000 jobs, Fig. 2. This does not consider the impact on the supporting infrastructure business.

The unfortunate underlying story is that this cyclic nature is not new to the industry, and seems to be widely accepted as part of the territory—boom and bust. With these cycles, employment has expanded and contracted; an accepted hazard of the industry.However, should this be acceptable? Is it reasonable for a 159-year-old industry to simply ignore this huge imperfection, and accept that this is the way it will always be?

This is an industry that has taken on, and overcome, some huge technical challenges—from developing methods for producing shale oil and gas once considered unrecoverable, to drilling and producing in 10,000-ft water depths offshore. The technical challenges for this industry are easily analogous to those of the aerospace industry. This should be an industry that lures the greatest talents and finest minds, to help solve the extremely challenging technical and economic problems facing oil and gas operators. It should be an industry, where graduates can engage confidently in finding solutions without fear of risking their careers and their families’ wellbeing.

However, the reputation of the historic up-and-down cycles is frightening away the very people that should flourish in this industry, and thus have great careers. Growth of oil consumption is forecast to continue for at least the next two decades, in which there will very likely be more boom-and-bust cycles. With emerging, alternative energy growing, competition will be high for graduates. The industry offers big challenges, but it also must offer the security of a long career.

The question may be, how can the industry’s cyclical nature be changed? Yet, can we really expect to change the cycles of market pricing? Perhaps the question should be, how can the impact of price cycles be reduced, so that a strong workforce can be retained and business growth can be sustained?

Consequently, the goal should be to take steps that lessen the impact of oil prices, as they rise and fall, and provide a robust formula for maintaining a business model that weathers these changes. This poses the question of how we accomplish this goal.

The answer is likely to be multi-faceted. First, costs must be brought in line with revenue, and sound controls should be put in place that keep costs aligned with revenue. The second goal is sustained growth, regardless of market oil price. What may be required is a planned evolution of the industry.

BALANCING COSTS AND REVENUE

How can costs be reduced without downsizing the workforce? Certainly, there must be a cost/revenue balance to maintain profitability, yet a stable workforce is needed for companies to perform at a high level and sustain growth. Consequently, tools are needed to reduce costs, keep them in line with revenue, and provide the opportunity for sustaining growth.

REDUCING COSTS

Cost-savings can be obtained through either CAPEX reductions or operational efficiencies, or a combination thereof. These take the form of some specific, common sense steps.

Spending controls for CAPEX. The primary driver for all projects, regardless of size, must be disciplined spending. System designs should target the meeting of requirements and avoid exceeding those requirements. The focus should be on must-have designs instead of nice-to-have designs. Good cost forecasting and controlled design implementation are key instruments for spending discipline, and this likely means early design freezes.

Project sanction processes are an accepted means of ensuring sound design and thorough economic bases. However, as stated above, conditions are subject to sudden changes—today’s prices may not be in place when production starts. The temptation is to change the criteria, based on current market pricing. Consequently, here are some considerations that could smooth market price swings:

- Establish clear and concrete process steps with consistent economic measurements. Set up a well-defined approval threshold for all projects.

- Set a reasonable oil price benchmark to be used for all project sanctions. Benchmarks should be applicable for boom or bust conditions.

- Establish project exposure limits, based on good cash flow, debt ratios and revenue targets.

- Consider risk/reward sharing to maintain continuity, rather than fixed value and erosion or an unobtainable upside/cut-throat supply chain.

Equipment standardization may be an overused term and has been discussed for decades. However, few operators have applied this concept effectively. The advantages, benefits and limits have been much deliberated, mostly on a theoretical basis. Here are some thoughts on applying standard designs:

- Avoid preferential engineering. Use designs that meet the minimum requirements and avoid designing to meet individual preferences.

- Optimize designs. Simplicity in meeting requirements leads to lower costs and faster deliveries.

- Design consistency—the “design one and build many” principle works, if adhered to.

- Work with supplier standards. Suppliers are the experts on their products, and they use industry design guidelines to develop standard products. These meet the industry’s minimal requirements and are more cost-effective.

- Use configuration standards. Rather than buy components, buy systems.

- Establish supplier agreements, based on standard products that will facilitate stable pricing and consistent deliveries.

Use the “limit state design” philosophy to minimize costs:

- Design to meet minimal requirements set by accepted industry standards.

- Design components to be fit-for-purpose, meaning that designs will do what they are designed to do without exceeding minimum accepted design requirements.

- Meet industry standards instead of surpassing them. They are in place to provide guidelines for designing equipment to perform specific functions in a safe manner. Using specialized requirements likely surpasses industry standards. However, value added may not surpass value lost.

Operational (OPEX) cost reductions. The principal impact for reducing operational costs is to minimize offshore exposure. Below are some considerations to accomplish this:

- Reduce offshore manning requirements by moving the workforce off the platform to onshore locations.

- Reduce production facilities through reduced manning requirements. Savings can fold back into CAPEX, when implemented into the design phase, by reducing platform size to accommodate a smaller facility. Below are some considerations for reducing offshore facilities:

° Remote operation through virtual control and monitoring.

° Reduction of transportation costs for personnel and supplies.

° Reduced quarters, boarding, etc.

° Increased safety—less exposure to personnel for risks of travel, environment and work spaces.

- Reduce the boom-and-bust costs of workforce changes: training, learning curve risks, unemployment costs, separation costs, loss of personnel expertise and experience.

BALANCING REVENUE WITH COSTS

The key to balancing costs and revenue is a comprehensive understanding of projected revenue. This, of course, is developed through accurate revenue forecasting and sound production planning. All operators work hard at this, and they have their respective tools and processes to provide a good understanding of what can be expected, both short-term and long-term.

Some ideas to facilitate this knowledge are sustainable project planning and controlled growth. With knowledge of expected production over a long period, projects for identified prospects could be planned to ensure maintenance of production levels into the future. This planning also could accommodate sustainable, controlled growth. Good project planning can provide paced development, controlled financial exposure and sustained work over a longer period of time.

HURDLES AND BARRIERS

Change from the status quo can be expected to meet some resistance and skepticism, especially where evolution of the industry is considered. The upstream industry has traditionally been very conservative with regard to changes and new technology. Below are some areas that will likely be hurdles to overcome in the evolution:

- Reluctance to be a pioneer. Most operators do not want to be the first to use new ideas or technology, and prefer for others to take the lead.

- Preferential engineering. Many operators, especially

the majors, have their own design requirements that they have developed. - Slow acceptance of new technology. Acceptance of new technology in the oil and gas industry takes about 10 years. This is very different from other industries, where new ideas and technology are often cultivated.

- Protection of intellectual property. The industry is very competitive and extremely sensitive to sharing ideas with other entities, particularly competitors.

CHANGING THE GAME

What will it take to evolve the industry? Many of these aforementioned ideas are challenging for the upstream sector, and it will take an evolution of thinking and strategy. New perspectives may be needed on risk management to accommodate such an evolution. Here are some thoughts on changing the way that the industry functions:

- Innovative solutions. The industry must change the way that it thinks. This may well require a modification of the position on risk tolerance.

- Move the workforce by creating a virtual workplace for remote locations. This innovative consideration will need to work hand-in-hand with risk management.

- Embrace new technologies more quickly. Take advantage of new ideas that offer better efficiency and cost reductions. Innovative ideas are abundant in this industry, but technical leadership is needed from top executives to move on these more quickly.

- Standardization of equipment. As discussed, this is an instrument that has been recognized as having powerful potential, but has not implemented effectively.

- Industry collaboration. Significant experience and knowledge exist within the industry, yet they are isolated in silos of intellectual property. Bringing to bear all of industry’s capability on common challenges could be game-changing, in terms of solutions and cost-sharing; beneficial to all.

Possible tools for evolution. Making the above changes will require new thinking and some tools to make the changes. Here are some possible tools (Fig. 3) to implement changes:

- Data management through digital transformation: This is basically digital usages that inherently enable new types of innovation and creativity in a particular domain, rather than simply enhancing and supporting traditional methods.

- Engaging Internet of Things (IoT) technology: IoT allows objects to be sensed or controlled remotely across existing network infrastructure, creating opportunities for more direct integration into computer-based systems. This results in improved efficiency, accuracy and economic benefit, in addition to reduced human intervention.

- Virtual operation: This would allow remote monitoring and control of distant systems, such as offshore platforms.

- Industry collaboration on technology: Bring together all of the industry knowledge and expertise for the common purpose of problem-solving for everyone’s mutual benefit.

- Intellectual property sharing: Move away from silos of information and knowledge, and toward working for industry collaboration.

- Right-sized staffing: Instead of building internal infrastructure to address all aspects of business, use existing, external sources of expertise.

CONCLUSION

The compelling question is, do we accept this recent downturn as another cycle, or use it as an opportunity to change things? Change will take forward-looking thinking and innovation to do things in a better way. Industry leadership is needed, along with collaboration, to improve how the upstream oil and gas industry works. We must employ the developing tools that other industries are embracing.

We can maintain the status quo and do things the way that we have always done them, or evaluate how we are doing business and help evolve the industry. The choice is ours! ![]()

- Advancing offshore decarbonization through electrification of FPSOs (March 2024)

- What's new in production (February 2024)

- Subsea technology- Corrosion monitoring: From failure to success (February 2024)

- U.S. operators reduce activity as crude prices plunge (February 2024)

- U.S. producing gas wells increase despite low prices (February 2024)

- U.S. oil and natural gas production hits record highs (February 2024)