World War II: Meeting the demand of the Allied war effort

As World War II loomed, oil became indispensable. It was evident that without it, the war could never have been won. Compulsory in every form, oil was a necessary component to the assembly of bombs, and the manufacturing of synthetic rubber for tires, as well as that which was refined into gasoline for use in trucks, tanks and aircraft. Additionally, it was needed to formulate lubricants used for firearms and machinery.

By 1941, even before Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, the increased need for oil had become dire. Meeting the petroleum demand of the Allied war effort quickly became a main concern for the U.S. and its allies. Recognizing that the government’s ability to meet this demand for unprecedented quantities would require a more defined strategy, President Franklin D. Roosevelt established the Petroleum Administration of War (PAW), by Executive Order in 1942.

Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes was appointed to head the initiative. Ickes immediately set to work, using his own selection of American oil industry leaders to create the Petroleum Industry Council for National Defense, which later became known as the Petroleum Industry War Council (PIWC), to help generate ideas to meet the increasing war-time demands. Coincidentally, the agency held its first meeting on Dec. 8, 1941, the day after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Ickes’ agency was tasked with balancing the energy needs of civilians, private industries and government. Officials divided the U.S. into five districts to help ration oil and gas supply. Although the administration was abolished after the war was over, these five districts still exist today. They are now known as the Petroleum Administration for Defense Districts (PADD).

Because oil was such a valued commodity, it became a primary target for enemy forces, making production and transport challenging, and oftentimes dangerous. German U-boats were one of the leading threats, as approximately 90% of oil headed to the American East Coast, for example, was shipped from California and the Gulf Coast via tankers.

An American tanker, W.L. Steed, was just one case that illustrates how real this imminent threat was to the industry. On Feb. 2, 1942, the tanker, carrying more than 65,000 bbl of crude, was struck by a German torpedo and capsized just 90 mi from the mouth of the Delaware River.

It was threats, such as these, that made the transport of oil a national emergency. North America was producing 60% of the world’s oil at that time, making the matter even more pressing during war-time.

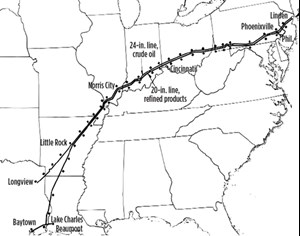

As a result, Ickes called a meeting in March 1942 to discuss a new pipeline strategy, originally called the Tulsa Plan. A plan was devised for the construction of the Big Inch pipeline that would be capable of sending 300,000 bopd from East Texas to Illinois refineries (approximately 750 mi), then from Illinois to New Jersey (approximately 1,000 mi), where it would branch off—one line leading to Philadelphia, Pa., and the other leading to New York City.

A second pipeline was then incorporated into the blueprint, The Little Big Inch pipeline. It was designed specifically to carry refined crude from the Gulf, meeting the Big Inch pipeline near Little Rock, Ark. This undertaking was considered, at the time, the greatest government-private industry cooperative effort ever achieved, as it required roughly 1,400 mi of pipe.

To carry out this new strategy, and to finish the pipeline project in time to help with the war effort, a nonprofit organization, called War Emergency Pipelines Inc., was formed by some of the industry’s leading corporations. Approximately 82 construction contractors and 16,000 workers were recruited to assist in the completion of such a massive job.

On Aug. 3, 1942, the first section of the Big Inch pipeline was laid in Longview, Texas. By the end of that same year, approximately 750 mi of pipeline had been laid, and oil was flowing to Norris City, Ill. Shortly thereafter, in August 1943, the project was complete. Despite several major setbacks reported by The Oil Weekly during construction, roughly 9 mi of pipeline had been laid, each day, to complete the job in less than a year. The Little Big Inch was completed just three months later.

The pipeline was completed just in time. In February 1943, The Oil Weekly reported a 10% drop in world crude production between 1941 and 1942, due to severe effects of the war.

These concentrated industry initiatives, which amplified oil production and distribution, were responsible for aiding the Allied war effort in a powerful way and, ultimately, they played a leading role in victory. ![]()