Oil and gas in the capitals

Russia’s economic situation has caught some analysts wrong-footed. But, the main characteristics of this situation—the sharp drop in GDP and industrial production for second-quarter 2015, and the ruble’s new depreciation—look much more like a transitional event than a structural downturn. The ruble/dollar exchange rate reflects, to some extent, oil prices. With the new downward turn taken by oil prices since July, the weakening of the exchange rate was not unexpected. However it has had some consequences for Russia’s economy.

Oil, ruble and depreciation logic. The nominal ruble/dollar exchange rate is now approaching levels of December 2013. Nevertheless, this has not created the same kind of emotion that we saw two years ago. We have to understand why—clearly no new massive speculation is taking place.

The ruble’s depreciation is clearly part of Russian economic policy. This has to be understood in the context of the role played by commodity prices (and then oil prices) in Russia’s budget and economy. Oil prices are not directly playing a significant role in Russian production, to the contrary of a widely (and wrongly) held opinion. However, oil (and, generally speaking, commodity prices) and gas are playing an important role in Russia’s budget process. Hydrocarbon exports are generating 45% to 50% budgetary revenues.

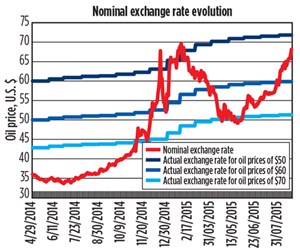

This is not the end of the story. Given that large producers are state-owned companies, the government relies on them for making critical investments in economic sectors not related to hydrocarbons. This makes oil and gas prices really critical. But, these commodities are traded in U.S. dollars, even if they could be paid to Russian producers in different currencies. This is why the exchange rate has become an important factor (see chart).

For a rough budget equilibrium, at December 2013 exchange rate levels, oil prices would have translated into 3,000 rubles/bbl. This implies that, for a then-$90 oil price, the exchange rate threshold would have been at least 33 rubles/$1.00. Now, if one considers that current oil prices (Brent) are around $45/bbl, this would put the exchange rate threshold at 66.6 rubles/$1.00. These computations are based on December 2013 prices.

But Russia also experienced serious inflation in 2014 and early 2015. This directly impacts the ruble’s denominated costs. In late August 2015, one could compute that the actual exchange rate threshold for budget equilibrium would be, more probably, between 75 and 80 rubles/$1.00. This implies that right now, the ruble, whose exchange rate is around 69/$1.00, is probably overvalued by 10%. But this overvaluation is making sense only if we look at the financial side of the problem.

Economics and politics of ruble depreciation. It is quite clear that the massive ruble depreciation since fall 2014 has largely benefitted profits, in rubles, of hydrocarbon producers. It also has benefitted other producers, be they in industry or agriculture. Losers in this process have been the financial sector and households.

Now, a significant contraction in both GDP and industrial production, Russian unemployment is pretty low and even declining. The government is forcing the economic structure to change. It is trying to make it much less dependent on Western-oriented hydrocarbon exports and on Western financial markets for investments. This is a consequence of the Ukrainian crisis.

To some extent, the Russian government may have made its mind up on this point even before the beginning of the Ukrainian crisis. One dimension is the turn taken by Russia toward China and the fast developing cooperation, going from military to financial, with that country. Huge oil and gas contracts are the results of this cooperation. More subtly, the Russian government is trying to develop sectors that are more independent from Western markets and companies.

Nevertheless, such a program implies considerable investment, and it will put the Russian economy into a situation where it will be—for the transition—much more dependent on direct or indirect state support. And here, the government will face a dilemma. To boost its revenues, it will need to have a low ruble, as far as oil prices will be low. But a too-low ruble would damage household consumption and negatively impact private investment.

Of course, the government could rely more and more on budgetary spending and state enterprises to fund investment. Yet, this would change, progressively, the whole investment picture, putting in its hands a very important responsibility at a time when deficiencies in the governmental structure are widely apparent.

Obviously, Russian President Vladimir Putin is enjoying huge political support. His political rating reaches unheard-of levels in Western countries. It is, however, not certain that he will use it to implement sharp reforms, which are overdue in the Russian governmental structure. He would probably prefer to build some form of political consensus among the political elite. But this could be contradictory with building consensus in the population and safeguarding his level of political approval. Here, a choice must be made. ![]()

- Applying ultra-deep LWD resistivity technology successfully in a SAGD operation (May 2019)

- Adoption of wireless intelligent completions advances (May 2019)

- Majors double down as takeaway crunch eases (April 2019)

- What’s new in well logging and formation evaluation (April 2019)

- Qualification of a 20,000-psi subsea BOP: A collaborative approach (February 2019)

- ConocoPhillips’ Greg Leveille sees rapid trajectory of technical advancement continuing (February 2019)