Regional report: Russia

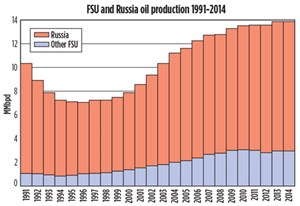

In 2014, Russia was no longer the world’s No.1 hydrocarbon producer (oil and natural gas, combined), having given up this statistical position to the U.S. Still, during 2014, according to Roskomstat and the Russian Federation (RF) Energy Ministry, the country’s production increased 0.7%, to 526.73 MMt (10.58 MMbpd) of crude oil and gas condensate, including 24.469 MMt (570,000 bpd) of lease condensate. This is a post-Soviet record high.

Oil and condensate production in December 2014 hit 10.67 MMbpd, also a record high since the Soviet Union collapsed. The data showed that Russia’s smaller producers, mostly privately held, increased their output 11%, to just over 1.0 MMbopd.

The Energy Ministry had predicted earlier in the year that oil output would rise 0.3%, to 10.6 MMbpd for all of 2014. This was achieved, and then some, despite the fact that greenfield output is struggling to compensate for declining production at mature brownfields. It also happened despite the lack of access to Western financing and technology that has occurred as part of sanctions against Russia, due to the conflict in Ukraine. Russia provides the vast majority of FSU oil output—according to the IEA, nearly 76% of 13.90 MMbpd during 2014, Fig. 1.

Meanwhile, gross natural gas output declined 4.2%, to 640.2 Bcm (58.74 Bcfd), both free and associated, including 73.5 Bcm (6.74 Bcfd) of casinghead gas, the second-largest such output globally. This Energy Ministry had predicted that gas production would rise 4.8% to 64.2 Bcfd.

RESERVES

For the first time, Russia officially disclosed its formerly secret data on the nation’s oil and gas reserves during mid-2013 (see World Oil, June 2014, p. 83). These data were later updated to reflect levels as of January 2014. As of that date, crude oil and condensate reserves (category ABC1) in Russia were officially put at 133.8 Bbbl, and gas reserves were set at 1,657.8 Tcf.

Meanwhile, BP, in its Statistical Review of World Energy, has partly revised the reported data on Russia’s remaining proved reserves. Its figures, as of January 2014, now stand at 93 Bbbl of crude and condensate, and 1,103.6 Tcf of natural gas. These BP-calculated data (at least in the case of oil) are regarded by some Russian experts as seriously underestimated.

Although the RF Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources (Minprirody) has failed to keep its promise to regularly publish official reserves data every year (no data set was released in January 2015), there are some indirectly related data that help to define the current scope. Thus, according to the same ministry, Russia in 2014 managed to increase its ABC1 reserves by over 4.0 Bbbl of crude, some 850 MMbbl of condensate and over 30.1 Tcf of natural gas. Corresponding figures for 2013 were gains of 4.46 Bbbl of crude and condensate, and about 33.4 Tcf of gas.

ECONOMICS/FISCAL REGIME

According to the IEA, Russia will need $2.7 trillion of energy investment during 2014-2035. Over the next 20 years, Russian oil and gas investment, alone, will amount to $2.086 trillion. This translates to $95 billion/year, on average. The gas industry will grow faster, with E&P investment likely to amount to $715 billion. The oil sector will get $750 billion for E&P, said the IEA in its investment forecast.

Fiscal regime. Russia’s oil and gas taxes are rather inflexible and do not link directly to profits. Generally, the fiscal regime that applies now consists of a combination of royalties (called mineral extraction tax (MET) or, in Russian, NDPI), corporate profits/income tax (CIT) and export duty. In addition, oil companies pay bonuses specified in licenses, and they contribute to social funds, excise duties, VAT (in case of exports), and road-use taxes. The tax burden is quite heavy (70%-80% on average), and it is killing low-efficiency projects.

Impact of lower oil prices. Declining oil prices have had an even more negative effect than sanctions. Although Russian production generally can withstand a drop to $30/bbl (and even to $10/bbl in a few fields), the price decline has diminished export receipts and depreciated the rouble. The rouble’s exchange rate against the U.S. dollar rose almost 70%, from less than 33.74 RR/USD to almost 56.82 RR/USD, during second-half 2014.

Still, Russia won’t be cutting its oil production, regardless of falling prices. Russian Energy Minister Aleksander Novak said that Russia plans to keep the 2015 production volume at 2014 level, which is about 10.5 MMbopd to 10.6 MMbopd.

Impact of sanctions. In the spring of 2014, the U.S. and EU imposed an array of sanctions on Russia, in response to the “annexation” of Crimea and Russia’s “involvement” in the crisis in southeastern Ukraine. The sanctions include restrictions on borrowing abroad by major Russian companies, and a ban on U.S. and EU companies helping Russia with Arctic, deepwater and shale oil developments (later, it also banned EU companies from drilling in the expanded Russian sector of the Black Sea).

Although the sanctions may have a limited effect, some Russian experts argue that this can threaten up to 25% of the country’s oil market and may lead to an eventual production loss of up to 2 MMbpd. At the same time, it also will push Russia to develop its own technology. Officials estimate that they’re “losing around $40 billion/year because of (the) geopolitical sanctions.”

Transactions. Оn Aug. 1, 2014, Rosneft closed a deal to acquire land drilling and workover assets in Russia and Venezuela from Weatherford for $500 million in cash. Rosneft acquired eight companies (part of the Weatherford group) involved in drilling operations in the above countries.

At the start of December, the Russian government issued a resolution on partial privatization of domestic oil giant Rosneft. As much as 19.5% of the company’s stock is planned to be privatized in 2015, and the federal budget can gain $8.5 billion from this financial operation. Last Dec. 18, Germany’s BASF and Gazprom agreed to call off an important asset swap that the two firms had planned for the end of the year. The general reason was the German company’s concern about sanctions.

Finally, at the end of the year, it was revealed that BP will acquire 20% of the shares of a key subsidiary of Rosneft, Irkutsk-based Taas-Yuriakh Neftegazodobycha, for $700 million to $800 million. While sanctions imposed by the U.S. and EU do not allow Russian firms to obtain Western technology, they do not forbid Western companies from buying Russian assets, such as interests in oil fields.

EXPLORATION

According to Minprirody, 33 commercial hydrocarbon discoveries were reported in Russia during 2014 (26 in 2013). Among these was the giant Pobeda field, found in the Kara Sea.

During May 2014, Natural Resources Minister Sergey Donskoy said that “the already discovered resource base will essentially be enough to provide for the yearly extraction of 600 MM t of oil (12 MMbpd) for the next 30 years. The Russian Federation has a substantial potential to expand its oil reserves. The most reliable, prospective oil resources found on the country’s territory make up 12.5 billion tonnes (90.9 Bbbl).”

Meanwhile, Dublin-based PetroNeft Resources has, thus far, acquired 1,055 km of seismic data and drilled 10 exploration/delineation wells in the Tomsk Oblast of Western Siberia. The block holds 2P reserves of 117.05 MMbbl, which includes 53.03 MMbbl at the newly found Sibkrayevskoye oil field. Last July, Oil India acquired a 50% interest in License 61. At Tungolskoye, an 11-well campaign was set to begin during second-quarter 2015.

DRILLING/DEVELOPMENT

Drilling. During 2014, some 6,867 new oil and gas wells were drilled in Russia, totaling 20.980 MM m (68.832 MMft), Fig. 2. This is equivalent to an average depth of more than 10,000 ft/well, compared to an average depth of 6,647 ft/well in the U.S.

The Russian drilling market is now dominated by Eurasia Drilling Company (EDC). In early 2015, Schlumberger agreed to buy 45.65% of EDC shares for $1.7 billion, with an option to purchase the remaining shares. According to data from REnergyCo, the total Russian rig fleet working during 2014 amounted to 980 units, but EDC data would suggest that only around 17% of these (mostly outdated) rigs would be powerful enough (1,500 hp and above) to drill the deep horizontal wells that are needed in the Achimov, Bazhenov and Tyumen reservoirs.

Last December, Piotr Galitzine, head of North and South American operations for tubular products firm TMK, said that horizontal drilling may now account for 30% of Russian production. “Horizontal drilling has already begun in the Russian Federation, albeit later than in the U.S., but on a large-scale basis,” said Galitzine. “The growth of horizontal drilling between the second half of 2013 and the first half of 2014 amounted to almost 40%.”

Oil development. During May 2014, Rosneft and BP signed an agreement to jointly develop Domanic tight oil deposits in the Volga-Urals area (Orenburg region). The agreement stipulates that BP will carry up to $300 million of Rosneft’s costs. If the pilot program succeeds, a JV will be created, and Rosneft (51%) will control it.

At the end of June 2014, Halliburton conducted the first contract geological assessment of Karasevskoe and Yuzhno-Tanlovskoe oil, gas and condensate fields, in partnership with Russia-based Fund Energy. The latter firm acquired the rights to develop these fields in public auctions held during 2012 and 2013.

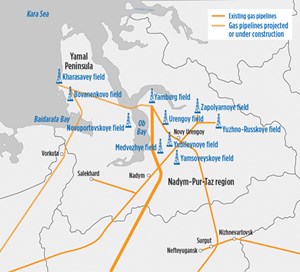

Last summer, multi-stage hydraulic fracturing was used in Gazprom’s Achimov deposits in the Nadym-Pur-Taz region. In addition, three-stage hydraulic fracturing was performed on each well by Moscow-based Eriell Group, working at giant Urengoy field in Western Siberia. Also, the first production well was drilled by Eriell at Yuzhno-Russkoye oil/gas/condensate field, known for some of Russia’s most hard-to-recover gas reserves.

Lukoil plans to invest $800 million to $900 million annually in oil development in the Nenets Autonomous Okrug (NAO). The plan was announced by LUKoil President Vagit Alekperov last November, after signing an agreement for the 2015-2019 period between the company and the NAO administration.

Natural gas development. In mid-September, Novatek launched the third stage of the Samburgskoye gas condensate field, developed by SeverEnergia, a JV between Yamal Develop-ment (Novatek and GazpromNeft) and Arctic Russia (Eni and Enel). The third-stage launch, which exceeds 183 MMcfgd, will enable the field to achieve peak production of 640 MMcfgd and more than 21,000 bcpd. Samburgskoye is in the Nenets Autonomous Region. Proved reserves are 3.2 Tcfg and 120 MMbbl of liquids. Production started in April 2012.

At the end of November, Gazprom and PetroVietnam signed an agreement to jointly develop two fields in Russia: Nagumanovskoye (Orenburg region) and Severo-Purovskoye (Yamal-Nenets Autonomous Area). Nagumanovskoye holds 194 Bcf of proven, in-place gas reserves, 14.3 MMbbl of recoverable condensate and 7.2 MMbbl of recoverable oil. Severo-Purovskoye has proven, in-place gas reserves totaling 1.52 Tcf, and recoverable condensate reserves of 58 MMbbl.

On Dec. 22, expansion of production capacity was begun at Gazprom’s giant Bovanenkovo gas condensate field on Russia’s Yamal Peninsula in the Arctic, Fig. 3. With proven reserves of about 167 Tcf, Bovanenkovo was put onstream during October 2012. Expanding production capacity at Bovanenkovo, the peninsula’s largest gas deposit, will help increase local output 50% to 8.25 Bcfd. Bovanenkovo should reach annual output of 10.54 Bcfgd in three years, and eventually more than 12.8 Bcfgd.

PRODUCTION

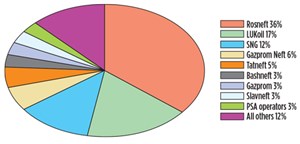

Oil. Three-quarters of Russia’s 10.58-MMbpd crude-and-condensate output were pumped by five major Russian oil companies—Rosneft, LUKoil, Surgutneftegaz (SNG), Gazprom Neft, and Tatneft, Fig. 4. Considering each producer’s share of national output, as well as the remaining state control over each operator, it can be calculated that during 2014, less than 32% of Russian oil production was actually controlled by the state.

Geographical distribution of both oil and gas production in Russia is uneven. The bulk of Russian oil (63% in 2014) is produced in Western Siberia, with much smaller quantities provided by the Volga-Urals and Eastern Siberian regions, whose shares are set to increase in the foreseeable future.

Roughly 46,000 bpd were added to 2014 Russian oil production, due to growth at such major oil felds as Vankor, Verkhnechon and Severo-Talakan in Eastern Siberia, as well as Korchagin, offshore in the Caspian Sea, and the Titov & Trebs group in the Komi Republic. Last September, the government said it plans to sell to China’s CNPC, 10% of the shares in Rosneft affiliate Vankorneft for $1 billion. The field’s oil reserves (all categories) are estimated to be 3.6 Bbbl, plus 2.7 Tcf of natural gas. Vankor’s peak production is now put at 510,000 bopd, or about 5% of Russia’s overall output. Last Oct. 20, Verkhnechon field produced its 30-millionth ton of oil since output began in October 2008. It has proved reserves of 600 MMbbl of oil and over 230 Bcf of gas.

At mid-December, RN-Uvatneftegaz, a Rosneft subsidiary, produced the 50-millionth ton (364 MMbbl) of oil since the Uvat project was implemented in 2004. In 10 years of operation, average output increased nearly 10 times, from 24,000 bopd in 2004 to about 200,000 bopd at the end of 2014. Today’s total recoverable reserves at these fields are almost 1.0 Bbbl. In total, 24 new fields were discovered by the Uvat project in the 2004-2014 period. Four of them were discovered in the last two years.

Difficult oil. Russian oil production is complicated by the dramatic rise in the share of hard-to-recover oil reserves, from less than 10% in 1961, and 30% in 1981, to over 55% of all the country’s known oil reserves in 2013-2014. Russia’s average rate of recovery now stands at 37.2%, compared to about 50% in the 1960s and over 40% in 2001. This results from rapid growth in the share of production from hard-to-access oil reserves. Despite early usage of EOR in the Russian industry, the share produced with such methods accounts for only around 3% of all national crude production, compared with 10% in the U.S. According to the IEA, Russia’s EOR-based output will amount to about 60,000 bopd in 2015, and roughly 400,000 bopd in 2030.

Although estimates of Russia’s future hydrocarbon production vary widely, most Russian experts agree that the country’s oil output will begin to decline in the years to come, as will production from older gas fields. The Moscow-based Energy Research Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences (ERI RAS) foresees that Russia’s overall, annual oil production will decrease to less than 10 MMbpd by 2040. LUKoil’s experts predict a drop to some 8 MMbpd by 2025, if the heavy tax burden on the national oil industry is not lowered.

Oil exports. Russian crude oil exports declined 5.7%, to 4.41 MMbpd in 2014, according to Energy Ministry data, due to a 5.2% increase in domestic refining. At the same time, crude export shipments of the other FSU countries across Russia’s territory (i.e., “transit”) decreased from 440,000 bpd to 390,000 bpd. The bulk of Russia’s oil exports outside the FSU (or almost 80% until recently) are to Europe. Overall, Europe’s dependence on Russian crude is about 34% of its total oil imports.

Natural gas. As opposed to oil, natural gas output is more unevenly distributed among Russian companies, with Gazprom accounting in the last few years for 70%-73% of national production (about 69.4% in 2014). The main natural gas producing area is the Nadym Pur Taz (NPT) region of Western Siberia.

Last December, the first stage of Urengoy gas field (Fig. 5) in Western Siberia, developed by SeverEnergia (a JV between Novatek and Gazprom Neft), reached its full capacity of approximately 640 MMcfgd and over 58,000 bcpd. Thirty production wells, including 18 horizontals, are in operation. The wells target the Achimov deposits, which have relatively large depths (approximately 12,140 ft) and a high share of gas condensate.

Last October, Jersey-based Zoltav Resources brought into production Zhdanov field within the Saratov region. The Bortovoy license contains several productive gas fields, a processing plant and significant prospectivity. Its proved-plus-probable reserves are 750 Bcfg and 3.9 MMbbl of oil and condensate.

In addition, Rosneft started experimental production from tight gas reserves of the Turonian formation at Kharampur field, in the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous District. Five leading scientific research and engineering institutes of the company are involved in the project.

Gas exports. By early 2014, quarterly volumes of Russian gas exports (incl. exports to the FSU) reached 55 Bcm (5.05 Bcfd). During 2013, Russian supplies accounted for 39% of EU natural gas imports, or 27% of EU gas consumption.

Gas companies. Gazprom is not Russia’s only gas company. There are many independent gas producers (IGPs), including oil companies, that control nearly a third of Russia’s gas reserves, or some 469 Tcf. However, they are not allowed to export that gas. They united in 2001, in their own professional association—the Union of Independent Gas Producers, or Soyuzgaz.

Gas outlook. ERI forecasts that annual national output from current gas fields will decline from 58.7 Bcfd to 27.5 Bcfd. However, overall gas production in Russia—thanks to sizeable additions from new and yet undiscovered fields—will grow by 2040 to some 82.5 Bcfd.

OFFSHORE/ARCTIC

Offshore operations are not nearly as developed in Russia, as they are in the U.S. Despite a vast coastline and continental shelf, offshore areas of Russia provided only about 390,000 bopd and 2.64 Bcfgd, equal to a little above 4% of national hydrocarbon output during 2014. Nevertheless, said Rosneft, the Russian continental shelf’s resource base is estimated at almost 337 Bboe.

Rosneft/Exxon Mobil joint efforts. Last August, Exxon Mobil and Rosneft received permission from officials to begin drilling a $700-million arctic oil well in the Kara Sea. The well, which is Russia’s most northerly, is the first of up to 40 offshore wells planned for the Arctic by 2018. The joint Exxon-Rosneft drilling at the Universitetskaya license, east of Novaya Zemlya, started in August, at a time when U.S. and European Union sanctions, in response to Russia’s intervention in eastern Ukraine, did not include already signed contracts.

But in mid-September, the U.S. banned its firms from supporting E&P activities in deep water, the Arctic offshore and shale projects, conducted by Gazprom and its oil arm, Gazprom Neft, as well as LUKoil, Surgutneftegaz, and Rosneft. In very late September, just before the expanded U.S. sanctions took effect, Rosneft and Exxon Mobil successfully completed Russia’s northernmost well—Universitetskaya-1. It discovered a major oil-condensate field in the Kara Sea, named Pobeda (which means “victory” in Russian). Rosneft plans to develop Pobeda field and begin producing in five to seven years.

By October 2014, due to the U.S. sanctions, Exxon Mobil idled nine out of 10 projects conducted jointly with Rosneft, except for Sakhalin-1, which is exempt. Rosneft will continue to drill in the Kara Sea on its own. Russia’s state commission on reserves confirmed that Pobeda holds recoverable reserves of almost 1 Bbbl of ultra-light oil and 16.71 Tcfg.

Last September, Rosneft started production on the northern tip of Chayvo field, offshore Sakhalin Island, enroute to reaching planned oil capacities in 2017, and gas capacities in 2027. Also, last fall, Rosneft (66.67%) agreed to set up a JV with Petrovietnam, to develop two shelf blocks in the Pechora Sea, in the Arctic off northwestern Russia.

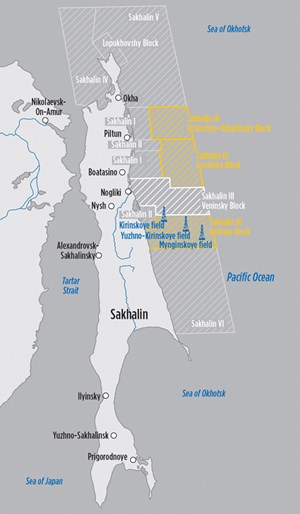

First Russian subsea installation. At the end of October 2014, Russian President Vladimir Putin ordered production to start from the country’s first subsea development, in 295 ft of water, Fig. 6. Gazprom’s Kirinskoye gas field is part of the Sakhalin III concession in the Sea of Okhotsk, 17.4 mi offshore eastern Russia.

LNG PROJECTS

Russian LNG exports should rise from about 1.33 Bcfd in 2013 to 1.84 Bcfd in 2017, when Phase I of Yamal LNG comes online. Further development of Yamal LNG, plus additional production start-up from Sakhalin LNG and eventually Vladivosok LNG, will support a ramp-up of volumes to 4.17 Bcfd by 2022.

Gazprom is ambitious about its future LNG assets, aiming to eventually control 15% of the global supply. One LNG plant in Sakhalin (Fig. 7) has gone onstream since 2009, and a new project, Vladivostok LNG in the Primorsk Territory, is planned for launching in 2018.

Sakhalin LNG. The majority of the LNG has been contracted to Japanese and Korean buyers under long-term supply agreements. Sakhalin Energy’s LNG plant has operated since February 2009, and it can export up to 10 MM t of LNG from two trains. A Gazprom subsidiary controls this project.

Project partners plan to have a third train in operation between 2016 and 2018. However, any extra new trains would require additional sources of gas, beyond Lunskoye and Piltun-Astonkhskoye fields. Partners Rosneft and Exxon Mobil continue to work on Sakhalin-1, which is “unaffected by sanctions, because it is carried out under a PSA.”

Yamal LNG is a Novatek-led project in partnership with Total and CNPC. It should be launched in 2016 with a total capacity of 15.0-16.5 MM t of LNG/year. At the end of May 2014, CNPC took a key role in development of the major Arctic gas project, as it committed itself to buy an annual 3 MMt of LNG. This project is technologically challenging, because the LNG plant will be situated on unstable permafrost. Shipping will take place via the Kara Sea, which is ice-bound for about 10 months of the year. Primary feedstock will be the 45 Tcfg in South Tambeyskoye field.

Despite Western sanctions, Total Chief Executive Patrick Pouyanne said on May 29, 2015, that he expected funding for the $27-billion project to be made available by lenders before the end of the year. Several days later, on June 2, Novatek co-owner Gennady Timchenko, said he was confident the Yamal LNG project would be finished.

Vladivostok LNG. This project implies the construction of an LNG plant in the Khasan District of the Primorye Territory. A three-train plant will have an annual capacity of 15 MM t of LNG. The first train will be commissioned in 2018. In February 2013, the project entered the investment stage.

Sakhalin 3 LNG. This is now the least developed LNG project in Russia. In September 2014, Gazprom announced a commercial gas discovery at Sakhalin 3’s South Kirinsky prospect. It soon became regarded as either a key source of supply for a third LNG train within the existing Sakhalin-2 scheme, or an additional supply for the planned Vladivostok LNG project or, alternatively, a main source of gas for a separate LNG project.

For the Sakhalin III project, Gazprom plans to use the gas resources of three blocks: Kirinsky, Ayashsky and Vostochno-Odoptinsky. Total gas resources on these blocks are estimated at 36.84 Tcf. ![]()

- Coiled tubing drilling’s role in the energy transition (March 2024)

- What's new in production (February 2024)

- Digital tool kit enhances real-time decision-making to improve drilling efficiency and performance (February 2024)

- E&P outside the U.S. maintains a disciplined pace (February 2024)

- U.S. operators reduce activity as crude prices plunge (February 2024)

- U.S. producing gas wells increase despite low prices (February 2024)