|

For a significant shift in company policy, this one was pretty quiet. In April, with the opposite of fanfare, Baker Hughes announced in a press release: “Baker Hughes believes it is possible to disclose 100% of the chemical ingredients we use in hydraulic fracturing fluids without compromising our formulations.”

The company goes on to emphasize that the move was made to find “a balance that increases public trust while encouraging commercial innovation. Where accepted by our customers and relevant governmental authorities, Baker Hughes is implementing a new format that achieves this goal, providing complete lists of the products and chemical ingredients used.”

With this move, Baker Hughes broke ranks with other companies in the same business, especially Halliburton, which does more fracing than any other service company in North America. They have long argued that 100% disclosure is unnecessary and puts their own trade secrets at risk.

States lead the way. This issue has been a long time in the making. Starting with Wyoming in 2010, 24 states have since enacted legislation that requires companies to report the chemicals they use for hydraulic fracturing. However, most state rules include exemptions for formulas that companies consider to be proprietary. This did little to ease the standoff between companies wanting to protect their trade secrets, and environmental groups who would settle for nothing less than true, 100% disclosure.

Back in April 2011, the Ground Water Protection Council (GWPC) and the Interstate Oil and Gas Compact Commission (IOGCC) created the first version of a dedicated website for oil and gas companies to voluntarily disclose data on the types and quantities of chemicals utilized in their hydraulic fracturing fluids. Operators using the “FracFocus 1.0” website would upload their data to the registry in Microsoft Excel format. The information was then converted into a PDF file and made available to interested groups and to the public.

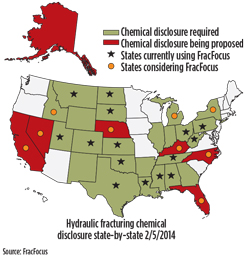

Several state agencies adopted rules requiring operators to enter the information into the FracFocus registry for each new well that was fraced. Currently, 15 states: Alabama, Colorado, Louisiana, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, North and South Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Texas, Utah and West Virginia, require disclosure to FracFocus. Other states are considering similar rules (see map).

FracFocus 2.0. Critics, as well as some users, of the website complained of flaws in its design. Besides the loophole regarding trade secrets, others pointed out that the website was not particularly user-friendly.

Last year, FracFocus was given a significant upgrade. The new FracFocus 2.0 was touted as a significantly better platform for searching wellsite chemical information. Using an XML database platform as well as GIS mapping technology to identify chemicals used in individual wells, users can search and print out reports by date ranges, chemical names or Chemical Abstract Service (CAS) numbers. Participating companies were notified that FracFocus 2.0 would become the exclusive method for submitting records to the website as of June 1, 2013.

In March 2014, a task force from the U.S. Department of Energy released a draft review of FracFocus 2.0, which concluded that companies were still withholding too much information. The review pointed out that almost 85% of the more than 68,000 wells registered on the site invoke some kind of trade secret exemption.

The report stated: “The Task Force favors full disclosure of all known constituents added to fracturing fluid with few, if any exceptions. A ‘systems approach’ that reports the chemicals added separately from the additive names and product names that contain them, generally should provide adequate protection of trade secrets.”

Secrets at risk? Halliburton responded to the task force report, generally acknowledging the importance of full disclosure, but expressing some significant issues: “[Halliburton] is concerned that the Task Force is minimizing the importance of trade secret protection, with potential consequences for oil and gas production, and American global competitiveness.” They maintain that hydraulic fracturing chemicals should not be treated any differently from other kinds of trade secrets. “There is no basis for singling out hydraulic fracturing in this manner. A trade secret is a trade secret and should be protected, regardless of the industry involved.”

Halliburton went on to warn that making the FracFocus database more searchable could allow for proprietary formulations to be reverse-engineered: “Even if chemical ingredients are not listed with the additives in which they are found, an experienced chemist for a sophisticated competitor—knowing the types of chemicals used in different types of additives—would be able to discern which chemicals are found in which additives.”

In general, the decision by Baker Hughes has been received cautiously all around. Environmental groups have applauded the decision, and say that the move proves the feasibility of full disclosure. Oilfield service companies are taking more of a wait-and-see attitude before deciding whether to follow suit.

|