|

| The Gulfstar One classic spar was installed at Tubular Bells field in the deepwater Gulf of Mexico in March 2014. The unit, which will be classed by ABS, is the first spar-based floating production system with major components built in the U.S. Hull fabrication was completed in Port Aransas, Texas, and topsides fabrication took place in Houma, La. (photo courtesy of Williams). |

|

Since 2010, the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) has developed and ensured compliance with standards and regulations that enhance operational safety and environmental protection on the U.S. Outer Continental Shelf (OCS). In pursuit of that goal, BSEE has issued major rulemaking changes that impact deepwater drilling operations.

One of BSEE’s most significant changes is that operators in the U.S. Gulf of Mexico (GOM) must implement and maintain a Safety and Environmental Management System (SEMS), in accordance with the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations 30 CFR Part 250.1900. This new regulation is based on API Recommended Practice 75, but has an expanded scope incorporating additional elements not contemplated in the API document.

The objective of the SEMS requirement is to give confidence that the production of oil and gas offshore can be carried out in a manner that promotes the security of life and property and preserves the natural environment. There must also be concentrated, multi-disciplinary efforts to comply with the more strict regulatory measures aimed at these objectives, not only because it is required, but also because the public has demanded increased transparency.

ESTABLISHING A BASELINE

Throughout their history, classification societies have developed rules and procedures for evaluating ships—focusing on structural and mechanical aspects—and have awarded class certificates to ships in compliance with these rules. In the early days of offshore activity, owners and operators thought to apply the same approach, and used class certificates for insurance purposes and as proof of compliance with international regulatory requirements. Over the decades since the first mobile offshore drilling unit (MODU) began working in the GOM, class requirements have evolved to address industry needs and the changing regulatory landscape.

Today, the offshore industry uses classification rules as a starting point in evaluating the safety of its operations, to evaluate asset and equipment reliability, and to better protect on-board personnel. Companies also seek approval in principle (AIP) as the first step in designing new solutions and innovative concepts.

As independent, externally audited third parties, class societies are integral to the compliance verification process for new technologies and floating structures used for offshore oil and gas operations in many global safety regimes. By reviewing plans and conducting surveys during construction, class societies verify that offshore structures, and their principal machinery and equipment, have been designed and built in accordance with technical rules and standards developed by the class society.

Class rules and guides help regulatory bodies develop acceptance criteria often these technical standards are used to establish a baseline. As a recent example, in 2013 the U.S. Coast Guard (USCG) issued a policy letter to provide guidance for regulatory compliance for floating offshore installations (FOIs) and FPSO projects on the OCS. The Policy Letter establishes alternative standards for certifying FOI and FPSO design and equipment—in addition to existing policies and procedures—and identifies three optional classification services to assist with compliance, with ABS maintaining its authorization to act on behalf of the USCG. Because the USCG has limited technical requirements specifically tailored to FOIs or FPSOs, determining the compliance matrix is challenging. Class societies, on the other hand, have developed specific requirements for each type of facility, based on experience and sound engineering principles. In the case of the USCG Policy Letter, concept-specific requirements from class rules—in addition to other recognized industry standards—are used as a baseline, along with additional requirements related to lifesaving, firefighting and fire-extinguishing equipment, and electrical and piping systems.

INVOLVING INDUSTRY IN RULE-MAKING

Class societies, operators, drilling contractors and the agencies regulating offshore operations periodically convene industry working groups focused on strategies that raise the bar for safety. These groups are working with class societies to develop more comprehensive risk management and accident prevention plans. A number of joint industry projects and academic technology research initiatives also are underway, with the goal of improving deepwater risk management.

The move toward risk-based facility inspection programs and more specialized services has led to greater recognition of the contribution that a class society can make to facilitate installation safety and integrity. Offshore asset integrity management programs are one example of how structures, equipment, traditional survey regimes and prescriptive class rules are being complemented with more proactive risk management processes.

Led by Executive Director Charlie Williams, the industry-sponsored Center for Offshore Safety (COS) was established in 2010 to promote offshore safety in the GOM and address compliance with SEMS regulations. The COS was vocal about involving established entities, such as ABS, from the beginning. It is important to note that SEMS compliance in the GOM must be verified by a third-party audit service provider. Members of ABS Quality Evaluations Inc. (QE) have served on the COS audit committee, helping to develop guidelines used for SEMS audits for evaluating SEMS implementation and maintenance. The company is accredited by the COS to conduct audits for COS member companies, a group that comprises more than 30 owners/operators, drilling contractors, service/equipment providers and affiliated industry groups.

Such industry input is critical to improving classification criteria. Rulemaking committees invite industry experts to participate in the development process to identify key issues and gaps and to propose changes and improvements to existing rules and requirements, based on practical application. As an example, ABS has announced plans to form the ABS Offshore Equipment Advisory Committee, which will bring together a group of industry experts focused on equipment safety, to further develop and modify specific requirements for critical equipment and systems.

In a separate working group meeting recently convened, and as an example of this collaboration, the ABS Mobile Offshore Unit Committee gathered industry participants to address improvement of emergency shutdown (ESD) systems on deepwater MODUs equipped with dynamic positioning (DP) systems, such as a drillship, Fig. 1. The focus of the discussion was unintended blackouts that disable DP capability.

|

| Fig. 1. Noble Corp.’s Noble Globetrotter I, a dynamically positioned, ultra-deepwater harsh-environment drillship under ABS class, began operating in the U.S. GOM in July 2012 (photo courtesy of ABS/Cris DeWitt). |

|

According to the working group discussion, the possible occurrence of spurious or errant signals can initiate ESD 0, or total unit shutdown. Another possible incident that can occur is an unwanted MODU blackout on location due to manual activation of the ESD system, either intentional or accidental. Recommendations generated from the working group discussion include a proposed requirement that prevents a single operation from causing a complete unit shutdown, and for a fire and gas detection cause-and-effect chart to be a required submission to the organization classing the MODU.

SIGNIFICANT CHANGES

Immediately following the Deepwater Horizon accident, former U.S. Interior Secretary Ken Salazar issued a report through the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation and Enforcement (BOEMRE) titled, “Increased safety measures for energy development on the Outer Continental Shelf.” Included in the report’s recommended changes, the Interim Drilling Safety Rule (effective Oct. 14, 2010) called for prescriptive requirements addressing subsea and surface BOPs, well casing and cementing, secondary intervention, unplanned disconnects, recordkeeping, well completion and well plugging.

On Aug. 15, 2012, BSEE issued the Final Drilling Safety Rule, which established new standards for casing and cementing, including integrity testing requirements; third-party certification and verification requirements; BOP capability, testing and documentation obligations; and standards for specific well control training, including deepwater operations. The Final Rule also addresses requirements for compliance with documents incorporated by reference; enhancing the description and classification of well control barriers; defining testing requirements for cement; clarifying requirements for the installation of dual mechanical barriers; and extending requirements for BOPs and well control fluids to well completions, workovers and decommissioning operations.

A significant change to the inspection and certification process was the requirement of third-party verification. A third party is defined as a technical classification society; an API-licensed manufacturing, inspection and/or certification firm; or a licensed professional engineering firm capable of providing the required verifications. The third party’s role is to verify that a subsea BOP stack is designed for the specific equipment used on the rig, that it is compatible with the specific well location, well design and well execution plan and that it was not damaged or compromised during prior service.

CERTIFYING NEW TECHNOLOGIES

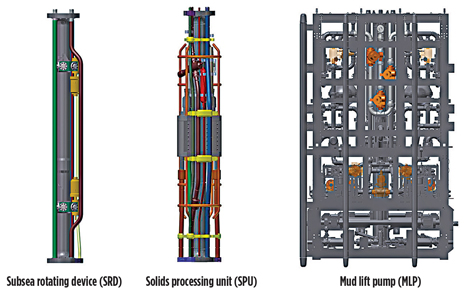

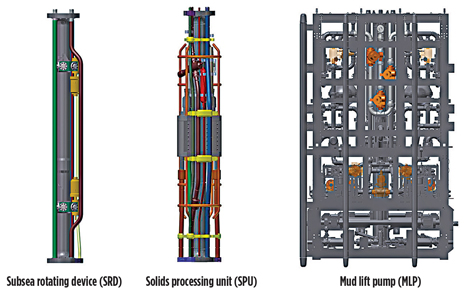

While BSEE has regulations for many pieces of existing equipment, it does not specify requirements for new technology concepts. Such was the case with Chevron’s dual-gradient drilling (DGD)system (Fig. 2) on the Pacific Santa Ana drillship operating in the ultra-deepwater GOM. For the industry’s first DGD integrated drillship, certification/verification became a project requirement in developing and implementing the technology, with BSEE requesting that the DGD system be verified independently by a Certified Verification Agent (CVA). As part of the acceptance process for the new technology application, ABS was nominated as the CVA and provided a review for the primary system components following the guidelines outlined in 30 CFR 250.912.

|

| Fig. 2. For the industry’s first integrated DGD drillship project in the GOM, Chevron enlisted ABS as the CVA. In addition to reviewing the surface equipment, ABS prepared design reviews of the DGD system’s subsea components, including the mud lift pump, subsea rotating device and solids processing unit (image courtesy of Chevron Corp.). |

|

Knowledge-sharing on such projects provides a foundation for performing the CVA scope of work and classification. It also allows the class society and operator to establish the proper standard that must be met while certifying new technology and, ultimately, providing the framework for developing new rules and requirements addressing this type of technology.

SAFETY IS CRITICAL

Best safety practices are most effective when they are developed and implemented impartially and objectively. The industry can only continue pushing the boundaries of what is possible if the new and enhanced offshore technologies applied in areas such as the GOM are safe and reliable, particularly in deep water, where risk and operational complexity are compounded. While owners and operators elect to maintain offshore vessels and facilities in class as part of asset integrity management, the classification process ultimately helps to keep units in compliance with technical and regulatory requirements.

A major component of class is facilitating information exchange for rule development and enhancement of classification services to the industry. Because industry continues to advance, class societies have to continue to update requirements to reflect the evolving needs of industry.

Independent organizations like ABS remain uniquely positioned to assist offshore stakeholders with regulatory compliance, based on global experience developing technical standards that promote safety and reliability on offshore structures, honed since the industry’s inception. Class will continue to work closely with industry and regulatory agencies to support the technical innovations that further expand responsible energy production for future generations.

|