Marcellus groundwater claims: A case for scientifically informed decisions

Claims of water well contamination need to be evaluated based on modeling of potential pathways of contaminants, sampling methods used and several other technical criteria.

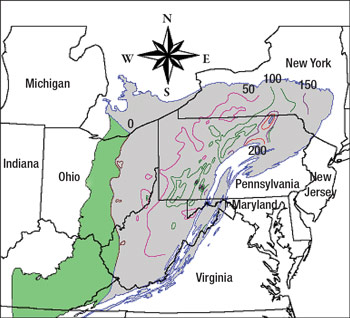

Claims of water well contamination need to be evaluated based on modeling of potential pathways of contaminants, sampling methods used and several other technical criteria.Lynn Kerr McKay and Laurie Alberts Salita, Blank Rome LLP Investment in the development of Pennsylvania’s Marcellus Shale gas resources (Fig. 1) has brought, and promises to continue to bring, lower energy costs and new jobs to the state. It has also attracted litigation alleging that well drilling, hydraulic fracturing and gas production have contaminated drinking water supplies and damaged property near some operations.

Recently, 13 families in Lenox township filed a lawsuit in Susquehanna County Court in which they allege that fracing contaminated their drinking water supply and made them ill. In support of their claims, the families cite the results of testing performed on their water wells that show elevated levels of barium, manganese, strontium and iron.1 Seventeen families in Dimock, Pa., have filed a suit claiming that drilling and operation of gas wells near their homes caused methane and various chemicals to flow into their water wells.2 In another lawsuit, a Washington County resident claims that fracing of gas wells on his property resulted in elevated levels of arsenic, benzene and naphthalene in his groundwater.3 In remarks to the press, the parties bringing these claims and their lawyers have displayed unwavering confidence that the alleged groundwater problems are caused by drilling and production operations.4 Media reports of landowner complaints alleging problems with water wells due to nearby Marcellus Shale operations abound. In addition, media coverage of reports funded by environmental groups, such as Riverkeeper in New York,5 has eclipsed reports of findings by federal and state agency scientists who have studied the potential environmental and human health impacts of fracing and gas production. Like the lawsuits, some media reports imply that Marcellus Shale drilling and production operations have caused widespread problems. Some lawmakers and regulators have adopted speculation and concerns about the potential for Marcellus Shale operations, specifically hydraulic fracturing, to contaminate water supplies and have cited this information as the basis for restricting E&P activities. However, according to the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), “Disruption of water quality or flow in water wells from drilling activities is often rare and generally temporary.”6 Hydraulic fracturing is not a new technique in Pennsylvania; nearly all oil and gas wells drilled in the state since 1980 have been fractured.7 The DEP has found no instance where fracing has contaminated groundwater.8 In addition, according to DEP Secretary John Hanger, problems with gas migration into water wells are not new or the unique result of Marcellus Shale drilling.9 Critical and scientific evaluation of information concerning the potential link between Marcellus Shale production activities and environmental problems is essential to appropriate judicial and regulatory decisions. Rigorous investigations can improve understanding of the extent to which Marcellus Shale operations may impact water quality, and data from these efforts can be used to form appropriate regulatory responses. Moreover, as technically sound data are preferred by courts, the results of deliberate and reasoned studies will assist juries in evaluating contamination claims. THE CASE FOR SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION Speculation about a possible connection between hydraulic fracturing and groundwater contamination has fueled opposition to industry’s drilling, production and waste management practices. For example, the New York State Senate has imposed a moratorium on new drilling in the Marcellus Shale until May 15, 2011.11 In justifying the moratorium, the bill’s sponsor noted possible, but unidentified, “catastrophic effects on our natural resources and families” and concluded, without support, that chemicals injected into the Marcellus Shale “work their way into the regular water supply.”12 The Delaware River Basin Commission (DRBC) also imposed a de facto moratorium by requiring that all shale gas extraction projects within designated areas of the basin (Fig. 2) receive commission approval, which will not be granted until after the commission adopts new rules.13 The commission expects to publish draft regulations by the end of the year. In announcing this requirement, the DRBC executive director said Marcellus Shale gas projects in areas of the basin “may individually or cumulatively affect the water quality ... by altering ... physical, biological, chemical or hydrological characteristics” (italics added) of waters in those areas.14

As an alternative to moratoria or sweeping new regulations, increased enforcement staff, limited modifications and clarification of existing regulatory requirements may prove a better method for ensuring water quality in the Marcellus Shale. For example, since 2008 the DEP has doubled the number of oil and gas inspection staff and implemented new water quality standards and other changes concerning Marcellus Shale operations.16 In fact, Pennsylvania now has more oil and gas inspectors than Louisiana (one of the top four oil-producing states).17 Additionally, on Oct. 12, 2010, the Pennsylvania Environmental Quality Board (EQB) approved proposed changes to Chapter 78 of the Pennsylvania Code—administrative regulations governing oil and gas wells—which update specifications and performance testing, design, construction, operational, monitoring, plugging, water supply replacement and gas migration reporting requirements for oil and gas wells.18 Although “it was determined that many, if not all, Marcellus well operators met or exceeded current well casing and cementing regulations,” the proposed changes detail the requirements for properly casing and cementing wells, and reflect existing requirements for operators to restore or replace a water well supply that has been affected by oil or gas drilling.19 The proposed amendments also impose additional obligations on operators for well control, immediate response to gas migration complaints, reporting of pre-operational test results and routine inspection of existing wells.20 Before taking effect, the amendments will require review and approval by the Independent Regulatory Review Commission and the House and Senate Environmental Resources and Energy Committees.21 If approved, the regulations will likely take effect in December 2010 with publication in the Pennsylvania Bulletin. The EQB has also recently implemented changes to regulations permitting discharge of treated wastewater to Pennsylvania surface waters.22 The rules allow discharge of wastewater from natural gas E&P operations only if it is treated at a centralized wastewater treatment (CWT) facility and meets the following standards: maximum average monthly concentration of 500 mg/L of total dissolved solids, 250 mg/L of total chlorides, 10 mg/L of total barium and 10 mg/L of total strontium.23 The new rules, which became effective on Aug. 21, 2010, exempt existing, permitted wastewater discharges and discharges that are specifically identified in the regulations.24 This exemption includes existing CWT facilities that process oil and gas wastewater at currently approved levels.25 In addition, the rules prohibit publicly owned treatment works, which treat municipal wastewater, from receiving wastewater from gas operations, unless the wastewater has first been treated at a CWT facility to the standards set by the new rules.26 FURTHER STUDY BY THE EPA Marcellus Shale drillers and operators are regulated pursuant to state oil and gas and environmental laws. They are also subject to federal Clean Water Act regulations that control the disposal of flowback fluids into surface water.27 The Energy Policy Act of 2005 specifically excludes underground injection for purposes of hydraulic fracturing, except where it involves injection of diesel In response to recent concerns, Congress instructed the EPA to investigate the possible relationships between fracing and impacts to drinking water.29 Between 1997 and 2004, the EPA also investigated the potential impacts to drinking water from fracing of coalbed methane reserves. That investigation included analysis of more than 200 peer-reviewed publications, interviews with 50 employees from state or local government agencies and input from about 40 citizens who expressed concern that coalbed methane production had impacted their drinking water wells.30 The EPA found no evidence suggesting that the fracturing of shallow coalbed methane wells had contaminated drinking water wells.31 Given the significant investment in planning and efforts to solicit input regarding the study’s design and scope,32 the EPA’s new study promises to yield scientifically reliable data concerning the costs and benefits of natural gas development in the Marcellus Shale. Such data are vital to reasoned policy and judicial determinations. SCIENTIFIC EVALUATION OF PLAINTIFF CLAIMS When groundwater contamination claims reach the pretrial motion and trial stages, state and federal court rules for admission of scientific information and testimony by experts should serve as a limit on the influence of media reports and political agendas on the outcome of groundwater contamination cases. Federal courts applying Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals Inc. (1993) examine whether scientific evidence will assist the trier of fact and whether the evidence is the product of a reliable and scientifically valid methodology. Pennsylvania courts use a different, but related, admissibility standard articulated in Frye v. United States (1923), holding that scientific evidence is admissible if the methodology underlying it has general acceptance in the relevant scientific community, and that judges should be guided by scientists when assessing the reliability of a scientific method.33 These rules exclude consideration of opinions offered by unqualified lay persons. Compiling admissible evidence requires a technically based plan, careful collection and accurate analysis of data. Only reliable scientific evidence should be admitted to prove claims that Marcellus Shale drilling and production contaminated drinking water wells or caused injuries to those consuming water from the wells. Evaluating contamination claims. Litigants should not be permitted to recover damages for groundwater contamination simply by demonstrating that Marcellus Shale operations occurred near their property and that their wells contain elevated concentrations of certain contaminants. Additional evidence is necessary, including proof of a potential pathway between the Marcellus Shale well and the water well. Modeling of the possible movement of Marcellus Shale fluids or gas to a water well must be critically evaluated for reasonable and reliable findings concerning the path that the fluids or gas followed, how that path was created, and the rate at which fluids or gas are capable of moving through rock formations or soil. Obviously, alleged contaminants found in wells should be compared with known constituents in fluid or gas from the Marcellus Formation or materials used in drilling or production from that formation to determine whether Marcellus Shale operations could even be considered a source for the alleged contaminants. Petroleum engineers and hydrogeologists can help by examining gas well records and permits to evaluate operational issues, such as the performance of the well and the effect of drilling and production on the underground pressure in the rock formation. These experts can also assist with evaluating the mobility of various substances in soil and rock formations in the region. Geologists can provide information about the type and characteristics of local rock formations. This information can be used to determine whether it is possible or likely that fluids from deep in the ground migrated from one rock formation into another. Geologists can also help with locating old, improperly closed or abandoned wells or coal mines that could be alternative pathways for methane gas and other substances to contaminate drinking water wells. The accuracy and reliability of claims that certain materials are present at levels that are several times the state or federal limits depend on the methodology used to obtain and analyze water samples. Using standard sampling plans, methods and laboratories that have been reviewed and approved by the DEP or other relevant agency will help to ensure that data are reliable and admissible. It is important to obtain as much information as possible regarding other potential sources for contaminants allegedly detected in drinking water. Many of the substances that plaintiffs in the current groundwater cases claim are present at elevated concentrations due to Marcellus Shale operations occur naturally or as the result of other common activities, such as farming, handling and disposal of common materials such as gasoline, household trash or sewage, or other industrial operations near the property, including coal mining. For example, elevated nitrate in water wells is often due to application of fertilizer or sewage and wastes from livestock farming operations in the area. 34 Chemical concentrations in wells subject to litigation should be compared with corresponding concentrations in wells that are believed to be unaffected by hydraulic fracturing. For example, regarding barium, one of the contaminants identified by the Lenox township claimants, the EPA has noted that the “drinking water of many communities in Illinois, Kentucky, Pennsylvania, [and] New Mexico contains concentrations of barium that may be 10 times higher than the drinking water standard. The source of these supplies is usually well water.”35 This observation was reported many years before recent efforts to produce gas from the Marcellus Shale.36 Likewise, exceedances of drinking water standards by substances such as iron, total dissolved solids and manganese, as well as low pH, in groundwater quality testing in Pennsylvania, have been determined to result from naturally elevated concentrations of those substances.37 In addition, several methods exist for determining the source of elevated levels of minerals in water wells, including tests to assess the age of the contaminant and chemical fingerprinting—determining whether the materials in the water wells are present in the same ratios as in the water that has been injected or recovered, Fig. 3.

Producers should also consider collecting baseline groundwater and surface water quality data for an area where future production operations are planned. In some cases, producers may be required to collect pre-operational water quality data from the surrounding area before beginning to drill a well. If feasible, operators should also consider performing regular water quality testing after the well begins operating. Operators who collect such data should be aware that the DEP’s proposed amendments to oil and gas regulations require operators to provide any pre-drilling water testing results to the DEP and to water supply owners within 10 days of receipt.39 These precautionary measures may serve operators well in the event of future investigation or litigation based upon alleged groundwater contamination. Pennsylvania’s Oil and Gas Act40 includes a provision requiring an operator who affects a groundwater supply by pollution or diminution to restore or replace the affected supply.41 Where the affected supply is within 1,000 ft of the oil or gas well, the operator is presumed to have caused the alleged pollution or diminution unless it can prove at least one of five defenses articulated in the statute.42 An operator may be able to rebut the presumption that its activities on the land in question contaminated or diminished the water supply by, for example, providing proof that the alleged problem existed prior to the commencement of drilling and/or that the alleged pollution occurred as a result of some other cause. Without pre-drilling and ongoing groundwater and surface water quality data, operators may be unable to refute the presumption, be required to provide an adequate alternative water supply and, potentially, be held liable for other damages that may relate to an allegedly contaminated water supply. As of this writing, there have been no reported decisions in Pennsylvania discussing the impact, if any, of the presumption articulated in the statute upon groundwater contamination and/or land use litigation with respect to burdens of proof. The data required to rebut the presumption that drilling activities contaminated or diminished a water supply under the statute are among the same type of evidence that would be required to defend against claims for damages pertaining to a polluted or diminished water supply. Likewise, no reported decision has specifically addressed whether the presumption, and the attendant liability imposed by the statute, could support a finding of negligence per se where plaintiffs seek compensatory damages in a civil suit for groundwater contamination. Because courts have consistently required plaintiffs to prove causation in groundwater contamination cases—i.e., a causal connection between the drilling and the contamination of groundwater, as in Mateer v. US Aluminum et al (1998)—operators are well advised to collect pre-drilling and ongoing water data. Evaluating personal injury claims. Scientific evidence and expert testimony will also play a significant part in deciding claims that exposure to elevated levels of constituents associated with gas drilling and production caused residents to experience adverse health effects. In evaluating those claims, it is helpful to establish thorough health histories for each claimant and to identify relevant occupational, lifestyle and environmental exposures to agents other than the alleged contaminants for each claimant. This information may provide an alternative explanation for a claimant’s alleged diseases. Medical doctors can assist with analyzing these data and performing differential diagnoses. To prevail on a claim for injury based on exposure to a contaminant, a claimant must produce more proof than test results showing that constituents in his water well exceed a regulatory standard. First, the claimant must demonstrate that one or more of the contaminants to which he was exposed has been identified as a potential cause of his alleged injury or disease. For example, Lenox County residents claim that at least one plaintiff has suffered from neurological symptoms.43 The residents specifically allege that their drinking water was contaminated by barium, manganese and strontium.44 While strontium has been identified as a substance for which the EPA may develop a drinking water limit in the future, presently, there is no EPA strontium limit for drinking water.45 Assessment of studies reporting health effects of chronic exposure to strontium have identified only rachitic bone effects,46 not neurological effects, as being caused by ingestion of strontium. Likewise, the EPA has found that while some people who drink water containing barium in excess of the maximum allowed concentration over many years could experience an increase in their blood pressure, it has not reported any association between barium and neurological effects.47 Although the EPA has determined that manganese, like other contaminants subject to regulation as nuisance chemicals, is not considered to pose a risk to human health,48 there have been studies suggesting that manganese could be associated with neurological effects at very high intakes.49 However, the EPA has cautioned that significant uncertainty exists concerning the level of manganese intake at which neurological symptoms might occur.50 An expert toxicologist can evaluate the findings of the manganese studies cited by the EPA and other research, and then offer testimony regarding the extent to which the studies actually support a conclusion that manganese can cause neurological effects in humans. In addition to showing that one or more of the contaminants found in his well have been identified as a cause of his alleged injury, a claimant must also demonstrate that his exposure to one or more of those contaminants was more likely than not the cause of his alleged injury. In most cases, a claimant must offer evidence of the amount of his exposure to the contaminants. The estimated exposure can then be compared to exposure levels reported in studies of groups of people who have been exposed to the same agent and were observed to have suffered from illnesses or diseases associated with that agent. Therefore, to prevail on their claim regarding neurological effects suffered by one of the parties, the Lenox township residents must show that the individual suffering from those effects was exposed to levels of manganese as high as or higher than the levels at which neurological effects were found to have been caused in groups of people who ingested elevated amounts of manganese. This evidence must be offered through an expert who is experienced and qualified to evaluate the claimant’s potential exposure to the alleged contaminants, and an expert who can competently diagnose the claimant as exhibiting signs of exposure to manganese. CONCLUSION The success of efforts to explore and develop Marcellus Shale gas resources depends on continued critical and scientific evaluation of information concerning all aspects of this enterprise. Scientific evaluation is essential to the fair resolution of claims regarding water well contamination. Reasoned and technically informed assessment of available data is also vital to determining the appropriate level of regulation, best practices for producers and allocation of resources to address environmental impacts and potential health effects.

LITERATURE CITED 1 Suzanne Berish, et al. v. Southwestern Energy Production Co., et al., Susquehanna County Court of Common Pleas, Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, No. 2010-1882CP, Complaint, ¶¶ 16 and 18.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

- Coiled tubing drilling’s role in the energy transition (March 2024)

- Shale technology: Bayesian variable pressure decline-curve analysis for shale gas wells (March 2024)

- Using data to create new completion efficiencies (February 2024)

- Digital tool kit enhances real-time decision-making to improve drilling efficiency and performance (February 2024)

- E&P outside the U.S. maintains a disciplined pace (February 2024)

- Prices and governmental policies combine to stymie Canadian upstream growth (February 2024)

- Applying ultra-deep LWD resistivity technology successfully in a SAGD operation (May 2019)

- Adoption of wireless intelligent completions advances (May 2019)

- Majors double down as takeaway crunch eases (April 2019)

- What’s new in well logging and formation evaluation (April 2019)

- Qualification of a 20,000-psi subsea BOP: A collaborative approach (February 2019)

- ConocoPhillips’ Greg Leveille sees rapid trajectory of technical advancement continuing (February 2019)