Fast tracking for the future

FACILITY CONSTRUCTIONFast tracking for the futureMarathon’s Southwest Kinsale project shows contractors and operators how to accelerate award-to-completion timeM. V. Murray, Marathon International Petroleum Ireland, Ltd.

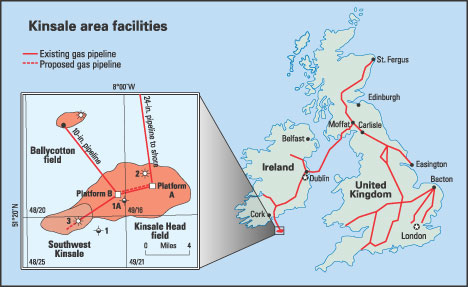

Southwest Kinsale, about 50 km (31 mi) off the south coast of Cork in Ireland, was discovered in 1971 and "rediscovered" in 1995. This second well was drilled to confirm a suspicion that this area of the Kinsale Head field was not being drained by the existing production wells on Kinsale Alpha and Bravo. Following a long period of commercial discussions, a gas sales agreement was finally achieved and the field was brought onstream on October 1, 1999, less than eight months after project sanction.

The single largest contract within the project was the EPIC contract, which included all of the marine construction and tie-in works, including umbilical installation (and procurement of same, post novation). This was awarded to Coflexip Stena Offshore Limited (CSOL), and with the bidding cycle on contracts completed by April 1, CSOL had only six months to complete its part from design to installation. A key enabling element was Marathon’s confidence in CSOL’s ability to deliver in terms of safety, quality and schedule, which meant the company was free to select the subcontractors. Development Concept The agreed development was a single-well tieback to facilitate gas sales on a depletion basis only, i.e.:

However, because of the planned reconfigurations of Kinsale Alpha and Bravo and the (still remaining) possibility of gas storage service, several design variations were possible, e.g.:

The chosen scheme was implemented without compromising redevelopment plans for Alpha and Bravo, and simultaneously maintaining the flexibility for future conversion to gas storage. Epic Contract The chosen solution was a 12-in. pipeline to the nearest platform (Bravo). This was not the cheapest option, but it optimized the early production profiles while maintaining the capacity for high gas deliverability, if the field is converted for gas storage use. Pipeline installation and protection strategy was left to CSOL to propose, within the following constraints:

All parties recognized that the pipeline would have to be protected (trenched or rock-dumped) because of the high level of fishing activity in the area. Given the number of contractors in the market, Marathon considered several proposals that varied more in their approach to the protection issue than to pipeline installation (reeled pipe). The final selection was a single-pass post-lay trench with provision for remedial rock dumping where the trench was below specification. This was the most pragmatic approach to protecting a line in difficult-to-trench ground conditions. Traditionally, subsea trees and umbilicals have been perceived as "long-lead" items and would determine the overall schedule of a subsea project. In this case, the items had to be available to meet a demanding schedule and, in addition, Marathon was seeking early delivery terms to give maximum offshore installation windows for the completion rig and CSO. The recorded delivery times speak for themselves:

The approach to the subsea control system was tailored to suit several constraints:

This approach of using available equipment or designs, without compromising quality or testing requirements, along with exceptional supplier cooperation, ensured that all parts of the subsea control system were available to meet all project deadlines, as required. As planned, Marathon also upgraded its existing subsea well to the new system, and included provisions for possible future wells.

Offshore Installation Given the short time available, a minimum number of constraints were placed on CSOL, especially concerning availability of equipment. A key schedule driver was delivery of the subsea tree by early June, which allowed maximum flexibility in organizing the well completion, ensuring that the potential for clashes with the pipelay / umbilical scope were avoided. The Glomar Arctic III, following a similar completion operation for Marathon on West Brae in the North Sea, installed the downhole completion in 18 days. Few problems were experienced during the work and the well was successfully cleaned up and flow tested ahead of schedule. The rig was demobilized and the well remained isolated until hook-up of the pipeline was completed. The main installation commenced in early September; and included pipeline, riser / J-tube, umbilical, valve protection structure and subsea tree hook-ups.

The work was completed by month’s end, in time for system commissioning by the deadline, as originally planned. As predicted, trenching of the chalk strata proved difficult even using CSOL’s MultiPass Plough towed by the Normand Pioneer. The original design philosophy of only making one attempt at trenching was followed, because a second pass would be of limited benefit and could in fact have destroyed the integrity of the existing trench. Areas of the trench that were out of specification (~40%) were rock-dumped to provide the necessary level of cover and protection. Key offshore personnel from all parties were involved in review sessions to ensure rapid exchange of views and experiences. The success of this approach is reflected in the absence of major "surprises," which are frequent in offshore operations on older installations. Cost Management How does Southwest Kinsale compare with other Marathon projects on cost? The project was under budget and considerably cheaper than the closest comparison, the Ballycotton project, Marathon’s first Irish subsea project, completed in 1991. Commercial considerations preclude use of actual dollar costs, but it is instructive to compare the cost breakdown (in relative terms) between the two projects (see table).

Significant reductions were targeted and achieved in all areas of the project, most notably in project management and topsides costs. Project management costs were significantly reduced because:

Today, subsea projects do not need armies of people "managing" the work; they only require a few highly trained and motivated individuals, who are willing to work together to get a job done efficiently. There is no doubt that some of the cost savings are a result of market conditions at the time of tendering. Nevertheless, a significant and repeatable contribution was made by the combination of contracting strategy, "fit-for-purpose" design philosophy and streamlined decision making within the management team. What benchmarks have been established for future projects? Can we now routinely expect deliveries such as:

If this can be maintained, and we see no reason why not (subject to production capacity), then many subsea projects become "commodity-projects," i.e., the schedule is driven only by availability of materials and installation equipment, and not by design / engineering time. This may improve the economics of many projects due to:

The challenge is for the industry to build on these

successes and make subsea projects (shallow and deepwater) more and more routine – without sacrificing

the quality and attention to detail that is essential for long-term reliability.

Acknowledgment I would like to thank Marathon International Petroleum Ireland, Ltd. for permission to publish this paper, and acknowledge the support and expertise of all Marathon staff and contractors who helped make Southwest Kinsale a successful project. Marathon recognizes the assistance provided to the project by Bord Gáis Éireann (BGE) and the European Union Trans-European Networks Scheme (TENS).

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Applying ultra-deep LWD resistivity technology successfully in a SAGD operation (May 2019)

- Adoption of wireless intelligent completions advances (May 2019)

- Majors double down as takeaway crunch eases (April 2019)

- What’s new in well logging and formation evaluation (April 2019)

- Qualification of a 20,000-psi subsea BOP: A collaborative approach (February 2019)

- ConocoPhillips’ Greg Leveille sees rapid trajectory of technical advancement continuing (February 2019)