United States: Crude oil prices

CRUDE OIL PRICES2000: The cost of energy goes upMatthew R. Simmons, President, Simmons and Company International, Houston 2000 was a tumultuous time for the world oil markets. Prices began the year at far higher levels than most thought would ever be achieved again. Virtually all "experts" were sure that oil prices would soon weaken. Instead, they rose even more before coming back to earlier levels. Throughout the year, oil stories dominated the media – this had not happened since the 1970s. Highlights Of 2000 On the eve of 2000, there were grave worries that Y2K problems might disrupt supplies. By the end of New Year’s Day, these worries were gone. Many then assumed that massive amounts of hoarded oil would overhang the world markets until they were re-absorbed back into the normal oil system.

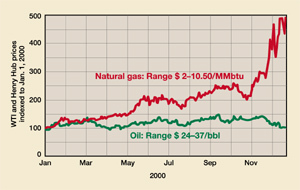

Oil prices move up. In mid-January, a bitter blast of Arctic air created a brief, but cold, 20-day winter in the U.S. This short burst of cold not only shattered the "Y2K hoarding myth" but also created the U.S. Heating Oil Crisis. This, in turn, kept the price of oil heading north. A few days into 2000, an old tanker named Erika literally fell apart off the coast of France, creating a nasty oil spill. This caused a further tightening of OECD tanker rules aimed at getting the rusty, unreliable tankers out of the system. In turn, it further tightened an already tight tanker market. By the end of 2000, spare tanker capacity that had been a permanent fixture of the tanker market for almost 25 years was gone. Tanker rates reflected this tightness by jumping almost three-fold in the course of less than 18 months. In an effort to cool down oil prices, the Clinton Administration raised the prospect of releasing oil from the U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve. In the meantime, Secretary Richardson embarked on an Energy Diplomacy mission to persuade the OPEC producers that more oil had to be placed on the markets. The trip succeeded in OPEC announcing an increase of 1.4 MMbpd. This would be the first of four announced OPEC production increases by the time 2000 came to an end. By late spring, gasoline prices were on the rise. Angry motorists were calling this a new "energy crisis" and were quick to blame various EPA rules on clean gasoline for $2 a gallon prices in some parts of the country. Nigerian civil unrest and terrorist pipeline bombings in Colombia happened so often during the year that neither became even newsworthy by year-end. In September, consumers throughout Europe began blockading the highway systems, ports and European / United Kingdom refineries to protest high energy prices, which were made even more exorbitant by very steep energy taxes. At times, these protests virtually shut down parts of the UK and France. These actually created the opening rounds of a debate on the role of energy taxes and their equity to both oil producers and petroleum consumers. Energy issues also became a hot political topic for the first time in almost 30 years. In late September, oil prices hit $37 a barrel and heating oil stocks in the Northeast were lagging 1999 levels by as much as 70%. As a result, the government announced a release of 30 million barrels of Strategic Petroleum Reserve oil to calm the very nervous oil markets and help ease the heating oil shortage in the Northeast. The mere announcement of this action drove oil prices down almost $10 a barrel before they began to climb once again. And the act became highly controversial from a political standpoint. The "missing barrel" factor. In the midst of this turmoil, the controversial topic of "missing barrels" reappeared on the oil scene. The IEA’s monthly supply and demand estimates for the world’s oil markets began to report a growing gap of excess oil supply over what they estimated oil demand to be as the year progressed. But none of this supposed excess was showing up in rising OECD stocks. To the IEA’s credit, the agency steered clear of announcing that the world had a new oil glut – as they repeatedly did through the previous "Missing Barrel Saga." But they could also not pinpoint whether their demand estimates were too low, or supply too high. So the data showing an excess quietly became a fixture in almost all supply / demand forecasts. OPEC’s oil ministers were also looking at the same IEA data showing "too much oil supply" and began to call for cuts in OPEC production to eliminate any prospect of another nasty collapse in oil prices. The call for possible OPEC cuts came at a time when IEA senior officials were warning that OPEC needed to produce more oil. The world’s petroleum data system was clearly out of control. By the end of November, various analyst reports began speculating on where the Missing Barrels might be. China and slow-steaming tankers led the list of guesses. But stocks of finished petroleum products, along with OECD crude stocks, were at 5- or 10-year lows. Rumblings from Iraq. As the year was winding down, Iraq’s leaders once more reminded the world that they were a still a force to be reckoned with. They expressed their unhappiness with the 10-year old oil sanctions and made it clear that they wanted unfettered access to money received from selling their oil. Over the previous four years, Iraq’s oil for food exports created almost $40 billion of funds going into the UN-controlled account. Iraq’s complaint was that it had only received $8.5 billion in goods and food. Iraq first demanded that the UN change the pricing of its oil contracts from U.S. dollars to the Euro, as the dollar was deemed in its eyes to be the "devil’s currency." Despite protests that this change will merely cost the Iraqis lost money – or, more exactly, cost the UN lost money since Iraq never received any direct money from any of its oil sales – the UN finally acceded to this request. Then came a request that Iraq’s prices be lowered so a surcharge to cover administrative costs could be directly charged to the buyers of its oil. This demand struck at the heart of the sanctions on Iraq, so the UN firmly denied this new plan. Therefore, on midnight, November 30th, Iraq shut off its oil; but no threats were officially tabled. To the contrary, various statements from senior Iraqi officials indicated that any export delays would only be temporary. There were also reports that a restored oil pipeline into Syria was now in full operation, but Iraq denied these reports. Sporadic tanker loading has taken place at Iraq’s Mina al-Bakr port, which handles about 40% of its export capacity. Iraq’s larger export terminal is located at Ceyhan, Turkey. One cargo was lifted at the end of December. Through the end of January, Iraq had held 90 MMbbl of oil off the market. Only time will tell whether Iraq is finally serious about a standoff of no added oil exports until its sanctions are lifted. The incident highlights the critical "swing producer" status that Iraq had become. OPEC: What spare capacity? The most significant "rest of OPEC" news in 2000 was growing evidence that most, if not all, of OPEC’s spare capacity is now gone. By almost all accounts, no spare OPEC wellhead capacity remains outside the UAE and Saudi Arabia. The UAE might have 100,000 to 200,000 bpd left, while Saudi Arabia supposedly has 1.8 million bpd. But even Saudi has a limit to how much short-term, extra oil it could produce if needed on a sudden basis. At the time Iraq shut off its oil, Saudi’s oil minister announced that Saudi could produce up to 1.8 million bpd within about 60 to 90 days. This gives credence to a growing suspicion that Saudi is also out of any spare "behind the valve" capacity. Low oil stocks, natural gas / electricity price surges. As a finale for oil’s eventful year, the U.S. petroleum stocks ended 2000 with only 1,470,000 bbl. The last time stocks were this low happened in 1982. Then, U.S. oil production was 50% higher than today and petroleum demand was 30% less. The U.S. petroleum complex is at "just in time" levels. If these events were the end to the remarkable oil story of 2000, the tale would be almost hard to believe. But the wildest part of this story was what happened to the other energy prices at year-end. At the start of 2000, natural gas prices were just over $2 per Mcf and the price of electricity throughout the U.S. was around $25 to $35 a megawatt hour. In the last week of December, natural gas prices exceeded $10 per Mcf, while electricity prices soared by as much as 10 times what they were as the year began. So 2000 came in like a lamb and went out like a lion – with a remarkably powerful roar. It now appears that virtually all three forms of energy have used up all of their cushion or spare capacity. It was this spare capacity which kept energy prices so low for over two decades. This era came to a violent end in 2000. Reviewing A Decade Of Oil Changes The fact that spare capacity in the petroleum system finally ended should have come as no great surprise. Look at the changes in the worldwide oil system from 1990 to 2000 to see how different the petroleum world now is. A decade ago, worldwide demand totaled just over 66 MMbpd, only 3.5 MMbpd higher than demand totaled in 1980. By 2000, worldwide demand had grown by 10 MMbpd in just 10 years, after demand from the former USSR fell by 5 MMbpd. Total demand, excluding the FSU collapse, increased by almost 15 MMbpd. To meet this increase, non-OPEC supply grew by 4 MMbpd, but almost all this growth took place in the first half of the 1990s. Between 1995 and 1999, non-OPEC oil supply flattened out. OPEC’s output made up the balance and finally grew to equal the same record levels last produced in the late 1970s, when all OPEC producers were going flat out to furnish a world hungry for more oil. A decade ago, the world not only had a significant cushion of shut-in OPEC supply, but also a comfortable cushion of petroleum stocks. OECD petroleum stocks at the end of 2000 were about the same level as the OECD countries had a decade ago. But since demand had soared, the system removed a full eight days of petroleum stocks, moving the petroleum complex steadily toward a "just in time" system, which has no tolerance for even the slightest supply interruption or demand surge without a crisis developing. One of the gravest energy mistakes made in the last half of the 1990s was a tendency for oil analysts and traders to describe any form of spare capacity not as a cushion, but as energy glut. What 2001 Has In Store The coming year will likely be a continual series of energy surprises. OPEC oil ministers seem intent on keeping stocks at razor’s edge, now that our financial markets seem to view even a few hours of extra energy supply as "glut." As long as this "just in time" mentality frames the mentality of how the oil system needs to work, we will stay on the brink between a true oil shortage and a real price collapse. Until the faulty data problems of the energy system are corrected, a great risk exists that we will run oil supplies to the precipice and accidentally create real oil shortages, not just unpleasantly high oil prices. There is an urgent need to finally discover what the minimum level of petroleum stocks really are, before we find out this answer after we drain stocks too low. There is still little data for energy planners to study on what decline rates the key oil fields of the world are now experiencing. This lack of key supply data makes all supply forecasts very incomplete. There is ample data which suggest that production is declining in almost all oil basins throughout non-OPEC producing countries. And there is mounting data which suggest that most OPEC producers are also beginning to experience declines in many early giant fields. There is growing evidence that supplies of rigs and other forms of drilling equipment are getting as tight as last experienced at the end of 1997 and early 1998. When spare rig capacity is gone, it will be impossible to keep supply growing to even offset these existing-field decline rates. The petroleum system is badly in need of expanded tanker capacity and more refineries, along with a major expansion in petroleum pipelines. The vast majority of oil observers passionately believe that oil prices will soon fall back to the levels most non-industry users enjoyed for almost two decades. But the same people held this belief a year ago. If prices do return to their "historical norms," this will also return the entire petroleum system back to the horrid financial returns which caused capital to flee the industry in droves. Too many companies spent almost a decade finding new ways to cut costs. No matter how much was cut, the financial returns stayed too low. The reason was simple: the price paid for oil and gas produced was too low. If prices fall back to this historical norm, it will also bring back the low returns that ensure no expansion of petroleum capacity. The industry is now badly in need of a long term "blueprint" for recreating excess capacity throughout the energy complex, which entails an expansion in the rough magnitude of about 30%. At the same time, most of the existing energy base –

from tankers to refineries to pipeline and power generation – needs to be rebuilt or totally refurbished.

The cost of this project will run into trillions of dollars.

|

||||||||||

- Applying ultra-deep LWD resistivity technology successfully in a SAGD operation (May 2019)

- Adoption of wireless intelligent completions advances (May 2019)

- Majors double down as takeaway crunch eases (April 2019)

- What’s new in well logging and formation evaluation (April 2019)

- Qualification of a 20,000-psi subsea BOP: A collaborative approach (February 2019)

- ConocoPhillips’ Greg Leveille sees rapid trajectory of technical advancement continuing (February 2019)