If I thought “exploration” was in trouble in the 1990s, when investment went to calling corner shooting and in-field development exploration, what about now? Some folks in Texas think that things have not been this grim since Gen. Santa Anna showed up with an army to take the place back in 1836! The same technology advances made since 2004, which “saved” the art of geoscience exploration, also could have killed it off, when they made shale oil possible, as well as long-bore horizontals with staged fracing.

The “however,” here, is that the technology needed to determine sweet spots (see this column, World Oil, December 2015) in unconventional development and find who-did-what-when with fracing and frac-disposed water, just may make possible the salvation of a group of technologists and technologies, which will be useful for the next round of what will be called the new, “traditional” exploration. We might label this new art, “geo-engineering.” How, then, will we relate x, y and z values of a reservoir to dynamic production data that are scalar by nature and recorded on a 1920s-vintage pressure gauge?

Where might the next round of traditional exploration be? It has been a while, since I worked international new ventures, but how about between Cuba and Mexico, even Cuba to the U.S.? The industry has long been wanting to explore the deepest Gulf of Mexico between the U.S. and Mexico, and the entire Caribbean, starting with offshore Colombia.

Another under-explored spot is around, and between, the Falkland Islands and the Falkland plateau. More and more, Morocco’s offshore structures are generating interest. And what about Timor? Another particular place, where I have worked and wondered about, is the Palmira subduction offshore Israel/Lebanon/Syria. Thank you to Noble, Zion Oil & Gas, and others for looking. We can still think about the Arctic. Maybe, someday, we can find a way up north that costs less than $200/bbl of oil extracted.

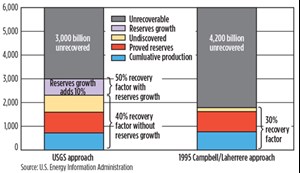

Collectively, what did we actually produce, worldwide, during the last 150 years? Well, less than half of the entire world’s reserves that have, so far, involved a drill bit. Note the chart on this page from a U.S. Energy Information Administration estimate. That is probably an underestimate, too. Let’s laugh at the undiscovered guesses, circa 2004.

Maybe the better question is “How did we leave behind so much?” Quick ROIs and quarterly reporting are only partly responsible. Fear of water in Sw is another. Limited tools are another. But, how about our attitudes at $100+ oil? “I do not need fancy tech, so I am not going to use it.” Translation, your management confined you and the engineers to using old tools. You know it takes a lot of different tools to find and evaluate a reservoir.

Worse, a plethora of exploration-generation products, and color-rendered geo-seismic-based interpretations, claim to have all the answers you want. Yet, not so admittedly, they are severely limited in content. The use of such assumptions in DHI’s leads you down the road to Dry Hole City. I see the claim of perfection at major professional conventions, and in just about everyone’s brochures. Sure, we need to market. But overselling has caused a lot of damage inside senior management, as well as their lack of willingness (“not again”) to invest in new ideas.

No one in this industry can prove 100% success with remote sensing, with geophysical, geologic or engineering tools. If you haven’t drilled a dry hole, you haven’t been doing much drilling. Risk reduction is still a valid demand from investors.

ROZ, EOR and EUR, all lead to ROI, maybe at even less than $30/boe. We may be playing with cool toys, but the real reason for someone using that tech is making money. “If Marathon could make big bucks pumping lemonade, we would do it, be the best at it, and have a lot less risk,” (Corky Frank, Sr. VP., MOC, personal communication, 1993).

Another great place to use, and continue to develop exploration technology, is in fault detection—as in when will the “big one” (earthquake) occur in the northwestern U.S., Japan or China—early warning systems, and permanent seismic monitoring. Check out the funding by the U.S. Dept. of the Interior, U.S. Forest Service, State of Washington, and State of Oregon. It is not an accident that projects and jobs are being created that revolve around human-induced fault movement related to oil activity. California and Oklahoma have many projects studying these issues. Texas is next. The down side is that you will age a bit, applying for federal grants.

The days of “I found it, you skin it,” contested between explorationists and engineers, are no longer valid in the new world order. ![]()