Offshore energy will power the world: 2021-2040 FPSO forecast

The offshore energy market is in flux. Economic effects from the Covid-19 pandemic, changing global attitudes toward energy, and the growing importance of ESG matters have disrupted the ways that companies do business. Although the energy transition is already underway, offshore oil and gas will continue to play a key role in providing energy for the world. According to the U.N., global population is expected to grow to 9.7 billion by 2050, with a large portion of population growth concentrated in the developing world. Energy companies, including those that produce hydrocarbons, are adapting to the changing landscape, which will impact the nature, pricing and financing of offshore oil projects.

As we look forward to the next 20 years, the following trends will dominate offshore oil and gas development: Offshore production will continue to move from OECD countries to developing countries; project financing will become increasingly difficult due to ESG and investor sentiment; and construction of new mega-FPSOs will increase as well as re-use of existing infrastructure.

Growing importance of ESG guides company investments. Sustainability and ESG policies play an increasingly important role in the oil and gas sector. As renewable energy and net-zero carbon emissions grow in popularity, oil and gas companies must follow suit. Pressure from shareholders and company boards has prompted publicly traded companies to create sustainability plans and commit to reducing carbon emissions. Additionally, many institutional investors and government funds have ESG policies that restrict the sectors and companies they can invest in. Publicly traded companies must pay close attention to these ESG issues or risk losing investors.

Although oil and gas have fallen out of favor rapidly in the eyes of many, the energy transition will take decades. Providing energy for the world’s growing population is complex, and hydrocarbons are still an affordable and reliable source. The changes discussed here will not happen overnight, but over the next 20+ years, as oil and gas operators strategically navigate the changing landscape of the energy sector.

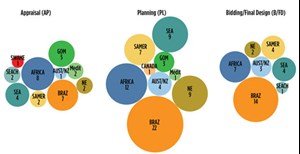

The large number of FPSO projects in the planning pipeline indicates that companies are committed to offshore oil and gas for the medium-to-long term, Fig. 1. Projects in the bidding/final design phase will be awarded in the next one to two years, and will be in operation within three to five years. Projects in the planning stage will be awarded in two to four years, and operational within four to seven years. Appraisal projects are the least developed, with a five-to-10-year timeframe from appraisal to operation. With more than 100 projects at least five years out from operation, it is clear that operators are making long-term, multi-billion-dollar commitments to the industry. Many of these developments are designed to produce for 20+ years. Companies are planning for an economic offshore oil and gas market to 2040 and beyond.

Operators consolidate assets to focus on core areas. In response to the changing landscape, field operators will begin consolidating assets. Faced with pressure to reduce carbon emissions, operators will divest high-carbon projects that do not provide a commensurate high economic return. One approach is to spin off these assets into stand-alone entities or form joint ventures. As a minority stakeholder, the company may choose not to roll up the financials and emissions to the parent company, thus reducing the visibility of their carbon footprint.

Many of the major oil companies have an upstream presence in more than 30 countries. Companies are beginning to focus on their best-performing areas that can provide sustainable financial success. Shell has stated it would focus on nine core upstream areas in pursuit of “value over volume.” In doing so, they must find a balance between projects that are financially, environmentally and politically attractive. Moving forward, the decision-making process for sanctioning projects will become more complex, as companies have to factor in ESG issues to the existing risk-return equation.

A tale of two NOCs. National oil companies Equinor and Petrobras are both consolidating and focusing on core assets, but with slightly different approaches. During the Norwegian firm’s 2021 Capital Markets Day, Equinor EVP for Exploration and Production International, Al Cook, announced the company’s plan to exit two Mexican deepwater blocks. Equinor also plans to offload assets in Argentina, Australia, Canada, Nicaragua and the U.S, in order to focus on high-profit, low-carbon (minimal greenhouse gas emissions) assets. The exit is part of Equinor’s plan to become a net-zero emissions company by 2050. In addition to reducing the number of oil and gas projects in its portfolio, Equinor has invested in low-carbon and energy efficient technologies like offshore wind, solar and carbon capture and storage. Similar trends will likely play out among other progressive NOCs and major oil companies in the coming years.

Petrobras is also divesting non-core assets but will remain focused on high-performing oil and gas projects. In January 2021, Petrobras sold its 49% working interest in a Brazilian wind farm and does not plan to invest in renewable energy, according to CEO Roberto Castello Branco. While Petrobras aims to design new projects with zero emissions growth until 2025, the company will capitalize on its key competency of discovering and producing oil and gas offshore Brazil. Profitability is the key driver for both Equinor and Petrobras. While some renewable projects may be attractive for European companies like Equinor, conventional oil and gas assets provide higher returns and are, therefore, more attractive for some companies, especially in the developing world.

Strategic exits will provide an opportunity for new players to develop these fields. NOCs, independents and local players will purchase and produce the assets that did not fit the portfolios of the previous operators. As majors consolidate their assets to focus on core high-performing areas, smaller companies will fill in the gaps left behind. Areas like Southeast Asia, Africa and the North Sea will see the most activity, particularly for fields that are small and mature. Compared to the massive discoveries offshore South America, these areas are less attractive for the large oil companies. However, they are ideal for smaller companies, which can find more economic ways to develop these resources.

Investment shifts from developed to developing nations. Operators will gradually transition from having widespread global footprints to focusing on a few strategic core assets. Another factor at play is the changing global attitude toward energy and greenhouse gas emissions. Investment in oil and gas projects in OECD countries like Australia, Canada, Norway and the UK is declining. All of these countries have ambitious carbon emission reduction targets in place, with Canada, Norway and the UK aiming for net-zero by 2050.

Profitability will be a major focus for companies moving forward. Another deterrent is that operating in countries like Australia, Canada and Norway is expensive. High labor costs and environmental regulations increase operating expenses. While these countries currently have tax incentives for oil and gas development, they are unlikely to last forever. Future oil and gas investment will be limited to massive fields with extremely attractive economics and quick payouts. While there have been some recent significant discoveries in these mature areas, such as Dorado in Australia, Bay du Nord in Canada, and Wisting in Norway, the largest offshore growth areas are in South America and Africa.

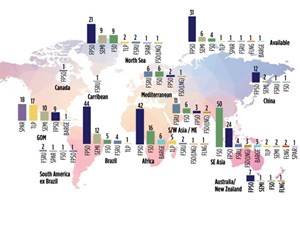

Although oil and gas have fallen out of favor with the public in OECD countries, governments worldwide use the revenue from hydrocarbon production to provide services to their citizens. Developing nations with oil and gas resources like Mexico, Brazil, Malaysia, Angola and Nigeria will encourage future investment, Fig. 2. In many of these countries, revenue and taxes from the oil and gas sector provide much-needed financial support for the government. The industry also drives the local economy, providing jobs and affordable energy. If upstream investment slows, the economy will suffer. When this happens, governments, including Brazil, Malaysia, Norway, Angola, and Nigeria, have revised legislation to encourage development of hydrocarbons. As operators exit less attractive areas, these nations will respond by providing tax and other incentives to drive local oil and gas investment.

National energy security will continue to play a role in the future landscape of oil and gas investment. This is particularly important in countries like India and China, which have massive populations to support. Energy is a key driver of these economies. They will continue to invest overseas, to ensure they have access to a stable supply in addition to developing domestic resources to avoid reliance on foreign imports.

The Terra Nova offshore project in Newfoundland, Canada, is a reminder that the energy transition will be complex. The field has produced 425 MMbbl of oil since 2002. Extending the field life by 10 years, to produce another 80 MMbbl, required an investment of CAD $500 million and upgrading of the FPSO in Spain. The work was scheduled for 2020, but did not commence, due to Covid-19, and the FPSO was laid-up. The future of the development was at risk, with several of the field partners not keen on proceeding.

Although Canada has pledged to reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 and has strict ESG policies, the project has received government support. The oil and gas sector plays an important role in Canada’s economy, accounting for 5.3% of the country’s GDP and supporting hundreds of jobs in Newfoundland (Natural Resources Canada). To save the project and boost Newfoundland’s economy, the federal government offered to invest CAD $205 million in the project and the provincial government has pledged to forgo up to CAD $300 million in royalties. Finally, on June 16, Suncor issued a statement, confirming that it and six partners had “reached an agreement in principle to restructure the project ownership and provide short-term funding towards continuing the development of the Asset Life Extension Project, with the intent to move to a sanction decision in the Fall. Rumor has it that four of the seven owners will opt out of the field, leaving Suncor and two others.

Terra Nova is an example of the challenges that companies and countries are faced with today. Operators must focus on profitable projects that meet investor expectations. Yet countries must do what is best for their citizens, whether that is turning to alternative energy sources or fostering conventional projects to create jobs, tax revenue and energy security.

Financing trends. ESG issues also are a factor in financing. Twenty-seven banks, including many involved in FPSO financing, have committed to the Poseidon Principles, which established a framework to assess and disclose whether financial institutions’ lending portfolios are in line with climate goals set by the International Maritime Organization (IMO). The IMO’s initial GHG strategy prescribes that international shipping must reduce its total annual greenhouse gas emissions by at least 50% of 2008 levels by 2050, while pursuing zero emissions as soon as possible in this century.

Leased FPSOs have traditionally utilized bank debt on a project basis, which is usually the least expensive way to finance. To qualify for new loans, most require compliance with the Poseidon Principles. However, this has not stopped banks from supporting new projects. In June 2021, 11 banks agreed to provide $1.05 billion to SBM for construction of the Prosperity FPSO, which is scheduled to begin operating in ExxonMobil’s Payara field offshore Guyana in 2024.

In addition to commercial debt, some FPSOs are funded by government loans through an Export Credit Agency (ECA). Japan’s JBIC is the most active ECA in this market, currently participating in funding for 11 FPSOs completed by MODEC. In each project, JBIC’s portion is approximately 33% of the total loan amount.

As the cost of FPSOs has increased, the number of financial institutions required for each loan has also grown. In addition, financing multiple units for the same owner or field operator increases the banks’ risk profile and may limit their capacity. In this case, alternatives are available, particularly bonds. In August 2019, MODEC issued a $1.1-billion bond to refinance the FPSO Cidade de Mangaratiba MV24, which began a 20-year lease in 2014. There was tremendous interest in the bond, which had an annual yield of 6.75% through the end of the charter contract. The following year, SBM issued a similar bond for one of its Brazilian assets, the FPSO Cidade de Ilhabela, which also began a 20-year lease in 2014. The $850 million non-recourse bond allowed SBM to repay its existing bank debt and return $280 million to shareholders.

There has been a slight increase in the number of operators arranging finance for the entire field development, including the FPSO. Major oil companies and large NOCs, like Equinor, usually own the production unit, while most smaller operators choose to lease the FPSO, to preserve cash. However, independent oil companies have decided to own three FPSOs currently on order: Leopold Sedar Senghor (Woodside Senegal), Energean Power (Energean Israel), and the MJ FPSO (Reliance India). This may be due to more attractive financing terms, as well as expectations for a long field life.

Financing offshore hydrocarbon projects will continue to be a challenge and will require the same creativity needed to overcome the technical challenges. There are various methods available to fund FPSO projects, and the financing process is becoming longer and more complicated. With the hydrocarbon space becoming less attractive to investors and projects becoming larger and increasingly complex, the cost to finance these assets is expected to rise. This will increase the cost of FPSOs slightly, but not to the level that would jeopardize the project economics for FID.

FPSO construction trends will evolve as financing and projects change over the coming years. In the past, one-third of FPSOs were new-builds. Today, nearly half of FPSOs are new-builds. Traditionally, new-builds were in harsh or remote environments like the North Sea and Australia. The topsides of modern FPSOs are too heavy–nearly 40,000 tons–for VLCCs to handle. Building new FPSOs from scratch allows the use of standardized designs. Repeatable designs reduce costs and improve efficiency for both contractors and manufacturers. Many companies, including BWO, MODEC and SBM, have designs for generic FPSO hulls. SBM has placed orders for six of its Fast4Ward hulls and MODEC has one M350 design under construction.

FPSOs are built in the same yards as other types of vessels. Shipbuilding is a cyclical industry, and the current backlog is growing rapidly, due to large orders for LNG carriers and large containerships. This will impact availability of shipyard slots for FPSO construction. In turn, this squeeze on shipyard capacity will impact price and scheduling in the short term.

In the 1990s, many FPSOs were built in European shipyards, particularly in Spain and the UK. Since then, activity has shifted to Asia. Initially, yards in Singapore specialized in converting tankers to FPSOs, while yards in Korea focused on purpose-built units. After construction of its new Tuas facility, Sembcorp has begun construction of new-built units in Singapore, as well.

The major shift in the past five years has been the rapid growth of activity in China, for both converted and new-built units. In addition, major oil companies now have FPSOs being built in China. Currently, shipyards in China and Singapore are very busy with floating production projects. CSSC (China), Keppel and Sembcorp (Singapore) have 6+ projects, each, while COSCO (China) and Daewoo (Korea) have 5+ projects, each.

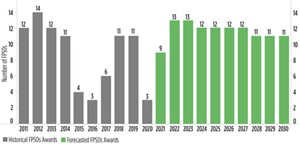

Although the number of new-builds is increasing, redeployment and conversions will still play an important role, Fig. 3. One-third of FPSOs will be converted oil tankers, typically younger hulls that are less than 15 years old. Additionally, more FPSOs will be upgraded and redeployed to new projects after finishing their current projects. Currently, there are 30 FPSOs available, with more coming off contracts as fields are depleted. Historically, 15% of FPSOs have operated on more than one field. Going forward, we expect this number to increase to 25%, given the number of idle units and their ability to provide a fast-track and economic solution.

As previously discussed, major operators are shifting their focus to mega-fields with large reserves, like those in Brazil and Guyana. NOCs, independents and local companies will take over the smaller fields divested by others, particularly in Southeast Asia and Africa. Production capacity of new FPSOs will follow this trend. More mega units (>200,000 boed capacity) and small units (<100,000 boed capacity) will be produced, with fewer large units (100,000-to-200,000-boed capacity). In addition, these units will be designed to maximize value with long plateau production, rather than volume with a sharp peak and fast decline.

Summary. In general, analysts are bullish on the price of oil. Crude prices should stay above $60/bbl and will increase as ESG pressure grows. In contrast to the past 10 years, there likely will not be a large growth in shale production, due to cost and environmental pressures.

As operators focus on monetizing their assets and bringing fields into production, there will be more opportunities for offshore development globally. FPSOs will continue to play a key role in offshore hydrocarbon development. Moving forward, the environmental movement and ESG issues will have a greater influence on how companies operate. Both will affect which projects are sanctioned, how they are developed, and how long they continue to produce. As changing dynamics in the energy sector drive up project prices, operators will narrow their focus to the most profitable projects. Despite these new challenges, companies will find a way to get offshore projects done.

- Advancing offshore decarbonization through electrification of FPSOs (March 2024)

- What's new in production (February 2024)

- Subsea technology- Corrosion monitoring: From failure to success (February 2024)

- U.S. operators reduce activity as crude prices plunge (February 2024)

- U.S. producing gas wells increase despite low prices (February 2024)

- U.S. oil and natural gas production hits record highs (February 2024)

- Applying ultra-deep LWD resistivity technology successfully in a SAGD operation (May 2019)

- Adoption of wireless intelligent completions advances (May 2019)

- Majors double down as takeaway crunch eases (April 2019)

- What’s new in well logging and formation evaluation (April 2019)

- Qualification of a 20,000-psi subsea BOP: A collaborative approach (February 2019)

- ConocoPhillips’ Greg Leveille sees rapid trajectory of technical advancement continuing (February 2019)