Offshore in Depth

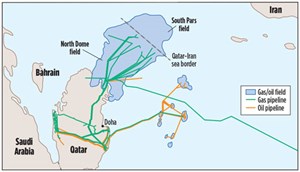

As U.S. unconventional gas producers gear up to export LNG, one of their biggest competitors is a huge offshore natural gas field that straddles the international boundary in the Persian (Arabian) Gulf between Qatar and Iran, Fig. 1. The North Dome/South Pars field contains as much as 1,260 Tcf of recoverable reserves, compared to the U.S. Energy Information Agency’s estimate of 338 Tcf for the entire U.S. Qatar has been the world’s largest LNG exporter since 2006, and has 14 LNG trains capable of processing 77 million tonnes of LNG per year. This compares to existing and planned LNG trains to export U.S. shale gas, which are slated to have a capacity of 57.6 tonnes of LNG per year.

Market forces put an end to moratorium. Qatar’s gleaming capital of Doha, and its outsized prominence on the international stage, were built on gas exports to Europe and Asia, under contracts that have natural gas prices indexed to the price of crude. In 2005, Qatar Petroleum (QP) placed a moratorium on further development in the North Dome, to conserve resources and evaluate the next phase of E&P investment. Since the oil price crash in 2014 (which eroded the profitability of Qatar’s LNG contracts), growing competition from Australia and the U.S., and the creation of an LNG spot market, QP has decided to take action to reduce costs and maintain market share. (At one point, Qatar supplied 32% of the world’s LNG. The International Gas Union estimates that its share has dropped to 29.9%.)

Qatar’s expansion plans. QP’s first step was to merge its Rasgas and Qatargas entities into a single natural gas company called Qatargas. In July 2017, Al Jazeera reported that QP plans to increase LNG production capacity 30%, to 100 million tonnes per year by 2024. The production increase will be made possible by new wells in the southern section of the North Dome field, with expected production of 2 Bcfd.

QP’s announced expansion comes as the Australians are on the verge of surpassing Qatar’s capacity with new LNG trains that will bring its total potential output to 85 million tonnes per year by 2018, and amid an LNG plant construction boom in the U.S. In addition, there is a surplus of LNG capacity. Qatar’s strategy is to leverage its advantage as a low-cost supplier (with delivery costs of $5.20/MMbtu, compared to $7.00–$8.00 for U.S. LNG) to maintain share and potentially discourage competitors’ future investments.

South Pars gains international investment. On the Iranian side of the international boundary, South Pars field has about one-third the reserve base of North Dome field. The development of its planned 30 phases has been hampered by international sanctions and limited access to financing. Relaxation of sanctions could accelerate development of South Pars. In July 2017, Total and CNPC announced that they will invest $2 billion to drill 30 wells and construct two wellhead platforms and two subsea pipelines, to deliver 2 Bcfd to an existing onshore treatment facility. Aside from a few exports to Iraq and Turkey, Iranian natural gas production is consumed in its domestic market. However, there is the potential for South Pars gas to eventually reach international markets. Four LNG projects were delayed or canceled in 2010, due to sanctions. These could be revived, but it would take a decade for them to be fully operational.

Boycott challenges Qatar’s ambitions. Long in the shadow of its larger neighbor, Saudi Arabia, Qatar has used the wealth generated by North Dome field to assert its separate identity, and an eclectic foreign policy that maintains relations with Iran while hosting a major U.S. military installation. In June, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt and Bahrain decided to punish Qatar for its support of opposition groups and imposed a land, air and sea blockade, to be lifted only if Qatar conceded to a list of 13 demands. Kuwait, the United Kingdom and the U.S. are all working to defuse the crisis.

On a visit to Doha on July 11, U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson met with Sheikh Mohammed bin Abdulrahman Al Thani, the Qatari foreign minister, who signed a memorandum of understanding to combat the financing of terrorism. Tillerson met with the foreign ministers of the four boycotting nations on July 12, but as of this writing, no progress has been made to resolve the impasse.

On July 17, an adviser to President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan said that Turkey is continuing to build-up its military presence in Qatar, in defiance of the Saudi-lead demand that the Turkish military withdraw from the emirate. The Hurriyet newspaper reported that Turkey has deployed dozens of commandos and artillery units in Qatar to protect the border and the security of the Qatari government. As tensions build, the potential for closing the Suez canal to Qatari shipments increases, and could disrupt the global LNG trade. ![]()