Regulatory roundup: Fractivists take to the ballot box, BLM drags feet on permitting

The world of oil and gas development in the U.S. is filled with public policy-related challenges, and this article will explore two of the more prominent issues that have come to the fore in recent weeks. The first part of this article will examine the results of the November 2013 elections, specifically a series of ballot initiatives brought by communities in Colorado and Ohio, which were designed to implement moratoria, or other restrictions, on the conduct of hydraulic fracturing operations within the communities’ respective boundaries. The second part of this article will examine the ongoing slowdown of oil and gas permitting activities for federal lands, and assess how this process was, or was not, impacted by the recent 16-day, partial shutdown of the federal government. LOCAL BALLOT INITIATIVES PRODUCE A MIXED BAGOne of the increasingly popular tactics deployed by opponents of oil and natural gas development, in the U.S., in recent years, has been to engage in efforts to convince small- to mid-sized cities and townships, in states with growing levels of development activity, to enact bans, moratoria or other significant restrictions on hydraulic fracturing operations. Having had almost no success in mounting similar efforts at the state and federal levels, anti-development activist groups, like Food and Water Watch (FWW) and the Oil & Gas Accountability Project (OGAP), have looked for better luck in smaller venues. And, over the past couple of years, they have experienced some measure of success in New Mexico and the Marcellus shale region. In 2010, Pittsburgh, Pa. (Fig. 1), became the first city to pass a ban on hydraulic fracturing. Since that time, more than a dozen cities and towns in New York state have passed similar bans or moratoria. In May 2013, Mora County, N. Mex., became the first county to ban ‘fracing,’ and anti-fracing activists are mounting similar efforts in several other counties, in that state. Additional bans, and/or moratoria, are being sought actively by crusading groups in several communities in California.

This is a very real, heavily-funded movement, which enjoys the support of wealthy entities like the Park and Heinz foundations. It presents a growing threat, and it should be taken very seriously by the industry. The Nov. 5 elections included ballot initiatives in four Colorado cities, as well as in three Ohio communities. The outcomes were decidedly mixed, for everyone involved. COLORADOIn September, Colorado was hit by devastating floods, along its Rocky Mountain front between Denver and the Wyoming border. Groups like FWW poured thousands of dollars, and extensive human resources, into the state, in an effort to feed false, misleading information to the media, both local and statewide, about both the flooding and pollution events that affected, or resulted from, physical assets of the oil and gas industry. Ultimately, most media outlets got the story right, citing official information from the state that showed that only very minor spillage, from oilfield sites, took place during the floods, and that the vast majority of pollution came from municipal waste treatment facilities in the region. However, the corrections came after many days of incorrect reporting, and the main goal of the anti-development activists had been achieved—concerns had been elevated among citizens, who only saw one side of the reporting. Unfortunately, there is little doubt that this series of events had a negative impact on the voting that took place in the cities of Boulder, Fort Collins, Lafayette and Broomfield. In Colorado, as in other states, the right to regulate the industry’s activities is, by law, reserved to the state. In recent years, few agencies have been as active as the Colorado Oil & Gas Conservation Commission in ensuring that their regulatory structure, and enforcement actions, have been modernized, to be relevant to current industry technologies and practices. State officials, including Democratic Gov. John Hickenlooper, worked hard to inform officials and residents in these cities that this was the case, prior to the vote. In addition, operators in the state also mounted a focused public-relations campaign in advance of Election Day. However, in the end, despite all of these efforts to educate the general public, the ballot measures up for consideration in Boulder (Fig. 2), Fort Collins and Lafayette passed by wide margins; the ballot initiative in Broomfield failed by a margin of just 13 votes, in the initial count, Table 1. A mandatory recount confirmed that the voters approved a five-year moratorium by 20 votes.

The Boulder initiative extends that city’s already-existing moratorium for five years, through June 3, 2018. It passed by an overwhelming 78%–22% margin (Editor’s note: This is not a surprise given that Boulder is known as “the Berkley of the Rockies,” a hotbed of ultra-liberal opposition to the industry). The Fort Collins measure places a five-year moratorium on “hydraulic fracturing and the storage of its waste products within the City of Fort Collins, or on lands under its jurisdiction, for a period of five years.” It was approved by a closer, but still significant, margin of 56%–44%. The Lafayette measure is very lengthy, and it bans not just ‘fracing,’ but any oil and gas development activity, in general. Notably, the measure contains no time limitation, and, therefore, would be the most difficult to reverse, outside of the state courts. It passed by a margin of 59%–41%. Industry representatives said that the outcomes, in the three cities that approved their measures, would have little practical impact, since there is no ongoing development activity there. While this is true, the outcomes do have an impact on public perception, which is one of the main goals of the anti-development movement. Unfortunately in Broomfield, city’s leadership had already entered into a memorandum of understanding with an operator that will allow it to drill, within the city limits, as many as 21 wells. The operator will be required to conform to a stringent drilling ordinance that the city put into effect last year; the ordinance requirements exceed state regulatory standards in several respects. Ultimately, Colorado’s courts will, most likely, decide whether the results in Boulder, Fort Collins and Lafayette will stand the test of law. The Hickenlooper administration is concerned about protecting the state’s authority to regulate oil and gas activities, and recently joined a lawsuit, filed by the Colorado Oil & Gas Association, challenging a similar ban, which was passed last year by Longmont, a city north of Boulder. Regardless, any development efforts that might have taken place within these communities will, ultimately, be delayed, and delay is always a goal of anti-development activists. OHIOElection Day was a little more kind to the oil and gas industry in the Buckeye State. There, two larger cities—Bowling Green and Youngstown—strongly rejected complex, and far-reaching, efforts to ban not just ‘fracing,’ but a variety of other activities, as well. However, Oberlin, a college town with just 8,300 residents, predictably passed a simple measure to ban hydraulic fracturing, Table 2.

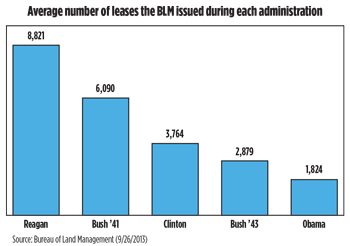

The Youngstown measure, which failed with only 44% of the vote, was a clear example of overreach by the anti-development activists. In addition to banning ‘fracing,’ the proposed measure went far further. It read: “It shall be unlawful for any person or corporation, or any director, officer, owner, or manager of a corporation to use a corporation, to deposit, store or transport waste water, ‘produced’ water, ‘frack’ water, brine or other materials, chemicals or by-products used in the extraction of gas or oil, within, upon or through the land, air or waters of the City of Youngstown. It shall be unlawful for any person or corporation or any director, officer, owner, or manager of a corporation to use a corporation to engage in the siting, within the City of Youngstown, of infrastructure supporting the extraction, processing, or transportation of shale gas or oil, including, but not limited to, compressor stations, pipelines, processing facilities, storage facilities and transportation facilities.” In other words, supporters of this short-sighted initiative were not content with banning exploration or implementing a ban on ‘fracing.’ They wanted to ban the construction of any new pipelines, storage facilities or other installations necessary to move oil or natural gas within the city limits. One can only wonder if such people would envision how their local distribution company would be able to deal with upgrading, or even replacing, the natural gas distribution facilities that already exist within the city. But it’s important to remember that such efforts are not about practicality—the goal is to create negative public perception about the oil and gas industry. The mere presence of such language, on an official ballot, no doubt made an impact, large or small, on a certain number of voters. Voters in Bowling Green (Table 2) were treated to an opportunity to approve an initiative that was obviously drafted by the same activist(s) who drafted the Youngstown measure—given the identical language used in several passages—but which went even further, in its banning efforts. The measure, which styles itself as a “City Charter Amendment Bill of Rights,” begins by calling for “a) Right to Clean Water; b) Right to Clean Air; c) Right to Peaceful Enjoyment of Home; d) Rights of Natural Communities; e) Right to a Sustainable Energy Future (Editor’s note: This sounds like a page out of the Obama administration’s playbook); f) Right to Self-Government; g) People as Sovereign; h) Rights as Self-Executing.” So far, so good. The language in the proposal then proceeds to ban everything that the Youngstown measure would have banned, but goes on to make it illegal to “engage in the creation of fossil fuel, nuclear or other non-sustainable energy production and delivery infrastructures,” and adds that “Corporations engaging in gas or oil extraction in a neighboring municipality, county or state, and persons using corporations to engage in gas or oil extraction in a neighboring municipality, county or state, shall be strictly liable for all harms caused to natural water sources, ecosystems, human and natural communities within the City of Bowling Green.” Thankfully, the voters of Bowling Green possessed the presence of mind to resoundingly reject the proposal, by a 75%–25% margin. SUMMARYIn the 2012 elections, the Barack Obama campaign famously declared Colorado to be “Ground Zero” in their effort to win the Electoral College. The 2013 election shows that the anti-development activist community has made the state a similar, strategic target, for its efforts to impede oil and gas development in the U.S. The state’s shifting voter trends, along with the fact that the industry is now active in areas that have not, traditionally, seen heavy oil and gas development, combine to create an atmosphere that is relatively conducive to influence by outside pressure groups like OGAP, FWW and their myriad of wealthy donors. While the Hickenlooper administration in Colorado recognizes the significant economic benefits that come with oil and natural gas development, and wants to preserve and promote them, the state’s existing trends could make maintaining this position more difficult, and, thereby, more politically risky over time. An editorial in the Washington Examiner on the election results stated, “Among the winners of Tuesday's elections were fear and paranoia. In four cities in Ohio and Colorado, voters were persuaded by Big Green scare tactics to ban a safe and environmentally friendly technology that is making America energy-independent.” While the Examiner is essentially correct—fear and paranoia, promoted by the industry’s opponents, were no doubt factors in the elections—the reality that the industry faces is that the creation of fear and paranoia have become an effective strategy, under certain circumstances. Until the industry finds an effective way to counter, we can only expect these activist groups to double down. The strategy was less effective in Ohio, obviously, as it has been in other, more traditional, oil and gas states, where such activist groups have struggled to gain significant footholds. But the development of shale plays in Ohio is in a very early stage, and so are the efforts of activist groups there. Things can change over time, as activists become more ingrained in specific communities. This happened even in the oil and gas king of states, Texas, where anti-oil and gas activists recently convinced the city council of Dallas to adopt an ordinance that, effectively, renders exploration impractical, although it is not an outright ban. It is a real challenge, and the industry in Colorado, and in other parts of the country, needs to find a more effective strategy, in the long run, to retain its social license to operate. BLM PERMITTING AND FEDERAL SHUTDOWNAn ongoing debate broke out during the recent, partial shutdown of the federal government about what effect it would have on the oil and gas industry. One aspect, which became something of a focal point, was about what the effects of a temporary halt in permitting activity, at the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), would be on the industry and on the states where the federal lands reside. And, indeed, given that all BLM permitting personnel are deemed “non-essential” employees, no permitting activity took place during those 16 days. The situation resulted in some interesting news reporting, and headlines, on the subject. For example, the Prairie Business Journal carried a story with this headline on Oct. 16, the day the shutdown ended: “Shutdown causes logjam of 500 drilling permits in ND.” This sounds like a dire situation, which would have a major impact on oil- and gas-related activities on federal lands in the state, until one reads the body of the story. There you find that, “About a month ago, BLM’s permit backlog was 450, North Dakota Petroleum Council Vice President Kari Cutting said in an email.” So, two weeks prior to the shutdown’s commencement, the backlog of permits at the North Dakota BLM office was 450; it grew by just 50 more a month later. Obviously, this is a fraction of the impact implied by the article’s headline. A few weeks later, in an article that attempted to make the case that the shutdown had actually cost taxpayers $2 billion overall, the Christian Science Monitor reported that the BLM had estimated that, nationwide, about 200 permits to drill had been delayed by the shutdown. So, a 50-permit build in a 500-permit backlog in North Dakota—which trails well behind states like Wyoming and New Mexico in terms of activity on federal lands—contributed to a delay in the issuance of 200 permits overall. So far, not exactly earth-shattering impacts. All of which leads us to this story, published on Nov. 7 by Utah’s Standard Examiner, whose headline reads, “Officials: Shutdown had big impact on Southern Utah.” Reading into the body of the story, one finds the following passage: “Michael McKee estimated his county lost approximately $370 million in revenue during the federal shutdown, as a result of federal lands not being accessible for gas or oil extraction. On Wednesday, he told a legislative committee, charged with considering the potential loss of federal funds, that the Bureau of Land Management has granted 1,400 applications for permits to drill this year for the county, with an existing backlog of 1,500. He estimates there was a loss in gas and oil revenue of $33.6 million a day, when the federal lands were closed down, because of the government shutdown in Washington, D.C.” Mr. McKee hails from Unitah County, where significant oil and gas production does exist. However, a brief examination of the numbers he presented to the Standard Examiner’s reporter are well outside the range of possibility. First, there is the reality that federal lands were not closed down, to oil and gas production, during the shutdown. Mr. McKee appears to confuse a temporary halt in permitting activities with a complete shutdown, of all oil and gas-related activities. Second, in 2012, per the federal government’s own data, the entire state of Utah collected around $164 million in revenues, from oil and gas activities on federal lands, within its borders. This is less than half the number that Mr. McKee claims his county lost in just 16 days. This is not meant as an attack on Mr. McKee, or the Standard Examiner’s reporter. Anyone who doesn’t deal with the complexities of federal leasing, and permitting processes, on a daily basis can easily become confused with the details involved. However, it is meant to help illustrate, what was a general overestimation, in the news media, of the impact that the shutdown would, and did, have on the oil and gas industry. What none of the referenced reports mentioned is the fact that the relatively minor hold-ups in permitting, created by the partial shutdown, were merely delays in a process that is already glacially slow, and is becoming steadily slower with each passing year. For proof, here is an excerpt from an Oct. 22 report by the American Enterprise Institute: “But oil and gas leasing under President Obama has been decreasing, even before the shutdown. The following chart shows the average number of new leases that the Bureau of Land Management issued during each administration. While the trend is down under all administrations covered, the Obama Administration had the lowest—half that of the Clinton Administration and a third less than the George W. Bush Administration.[vii]” So, the reality here is that a delay of 16 days, in the issuance of 200 permits, is basically a rounding error, in the general slowdown in permitting, that the BLM has been engaged in throughout the current administration, Fig. 3.

At the same time, any impacts on oil and gas during the shutdown were not even visible to the general public. The average guy driving his car to and from work every day had no problem stopping in at the local gasoline station to fill his tank; had uninterrupted natural gas flow to heat his water and cook his food; and saw no upward or downward impact to his monthly electricity bill as a result of the shutdown. The other side of this reality, of course, has been that the BLM, and other federal agencies with purview over the oil and gas industry, weren’t issuing new regulations during the shutdown, since the personnel who develop and issue such regulations are also deemed “non-essential” employees. Thus, a Federal Register that ran to more than 400 pages in early September ran only 10 pages in early October. After the regulatory frenzy that the industry has seen in the last four-plus years, this was a welcome relief to everyone. At the end of the day, the impacts to the industry from the stoppage of BLM permitting activity during the shutdown were minor, and will ultimately be subsumed within the general inertia of the agency’s overall activities. That doesn’t make for a very good news story, but it is the reality of the situation.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||