What's new in production

|

One of the biggest hurdles to explaining oil and gas production to the average person of adequate intelligence is the concept of scale. For example, in trying to illustrate how a well is drilled, fractured and produced, an educator usually employs some sort of a cartoon. We’ve all seen these: On top is a horizontal line representing the surface, usually festooned with little trees and birds and sun shining, along with some sort of drawing of a drilling rig. From this, a wellbore is shown descending through colorful layers of substrata until it reaches some sort of reservoir, where it takes a tight turn and continues on its lateral course. Often, there is a helpful disclaimer at the bottom: “NOT TO SCALE.”

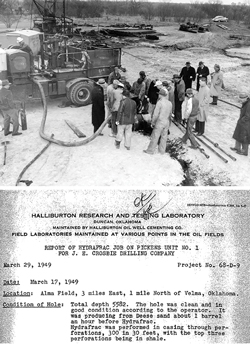

I should say not. But then, if you tried to illustrate your average Oklahoma petroleum well and keep things to scale, the rig would be a couple of blurry pixels and the wellbore would be a hairline on a slide 9 feet tall—which wouldn’t enlighten anyone. So, to convey how wells are drilled, the educator ends up with a lot of educatees who imagine oil and gas activity being conducted a couple of hundred feet down, instead of miles down. The same problem of scale exists with Deep Time. It’s easy to grasp thousands of years, but millions and billions are much more elusive. John McPhee, who has produced some of the clearest writing on geology, as well as many other subjects, illustrated the history of life on earth as something that extends from your shoulder to the tip of a finger. At this scale, he points out, all of human history could be wiped out with the swipe of a nail file. Swish. Mud through the ages. One of my favorite times in pre-history is that middle part of the Paleozoic called the Devonian. This period, which occurred between 419.2 million and 358.9 million years ago, is important for several reasons. It is often called “The Age of Fishes,” because of the proliferation of ocean species, not least of which were the tetrapods, or four-legged amphibians, some of whom crawled up on the land to become the ancestors of frogs, birds and men. During that same age, the first true forests formed on land, and the first insects populated them. It was a busy, muddy time. It’s when we got a lot of our oil shale. The landmasses that today include North America, Greenland and Europe were united into a single supercontinent called Laurussia. This vast area straddled the equator, and contained warm, shallow seas where populations of marine life multiplied. Late in the Devonian, seas covered a particularly stable part of the continental middle over what is now Oklahoma, and formed the Woodford shale, among others (see ShaleTech report). The conditions required to create this so-called “black,” highly organic shale were present: unchanging environment; silt from slow erosion of rocks, brought down by meandering rivers; a huge abundance of tiny marine organisms and plant matter; a lack of oxygen at the sea bottom; and almost unimaginable stretches of time. Then, over an even longer period during which the organic-rich mud was repeatedly buried, squeezed and heated, the Woodford shale became the gassy, oily resource it is today. When writing about geology, I have to consciously stop myself from saying “this happened, then that happened, and now we have this.” Because that fails to appreciate Deep Time, and time is what made this hydrocarbon age possible. We’re talking about 24,000,000,000 long, lazy Oklahoma days, give or take a few million. Napalm frac—a correction. Reader Carl Montgomery sent us some interesting comments about the first experimental fracturing job in Hugoton field, Kansas, in 1947. As we reported last fall (See “What’s New in Production,” November 2013), this was accomplished by injecting gelled gasoline, essentially napalm soap, into the formation. Carl writes: “I make my living hydraulically fracturing wells and have for a long time. I just wanted to correct one thing in the article. You say that ‘Halliburton engineers injected gelled gasoline’ in the first experimental frac in the Hugoton. Everything you say is correct in that it was done in 1947 and used Napalm, but it was done by Stanolind Oil, which was later know as AMOCO, which merged with BP. You reported that the results were “mixed,” but that well, which was an oil well, was still in production as of 2011. I don’t know what the gross production on that well is, but I am certain the frac job has paid for itself many times over.” Stanolind began life as Standard Oil of Indiana in 1911 with the court-mandated breakup of the Standard Oil Trust. Stanolind patented the HydraFrac technology in 1948, then licensed it to Halliburton, which did the first commercial frac jobs in the spring of 1949 in Alma field near Velma, Okla. Carl also sent along a lab report with detail and photo for one of these treatments (see figure). Note the almost complete absence of hardhats, Nomex coveralls and safety glasses. It was a very different world. |

- Applying ultra-deep LWD resistivity technology successfully in a SAGD operation (May 2019)

- Adoption of wireless intelligent completions advances (May 2019)

- Majors double down as takeaway crunch eases (April 2019)

- What’s new in well logging and formation evaluation (April 2019)

- Qualification of a 20,000-psi subsea BOP: A collaborative approach (February 2019)

- ConocoPhillips’ Greg Leveille sees rapid trajectory of technical advancement continuing (February 2019)