DAYSE ABRANTES, Contributing Editor, Latin America, and KURT ABRAHAM, Executive Editor

On Aug. 8, a contingent of officials from Brazil’s oil and gas activity regulator, the National Petroleum, Gas and Biofuels Agency (ANP), descended on Houston to convince producers that the country’s latest licensing rounds are a good deal for them. Yet, while the geology is certainly attractive, one has to wonder whether the licensing opportunities on offer make good financial sense for all but the largest of companies. These concerns are reinforced by requirements for the pre-salt round, one of which being that Petrobras act as operator, with at least a 30% interest, and that there is significant “local content,” with regard to provision of equipment and services.

ANP is offering its first Pre-Salt Licensing Round, featuring a production-sharing contract, and 12th (regular) Licensing Round, featuring concession contracts. The agency is full of enthusiasm, said its general director, Magda Chambriard (Fig. 1), after the very successful results of ANP’s 11th Licensing Round, held in May. In that round, 64 companies qualified to bid on 289 tracts distributed across 11 sedimentary basins, both onshore and offshore. Bids totaling $1.32 billion in signature bonuses were offered on 142 tracts (87 onshore, 55 offshore) awarded in the round.

|

| Fig. 1. Magda Chambriard, general director of Brazil’s ANP, said that during the agency’s 11th Licensing Round in May, 64 companies qualified to bid on 289 tracts distributed across 11 sedimentary basins, both onshore and offshore (photo courtesy of ANP). |

|

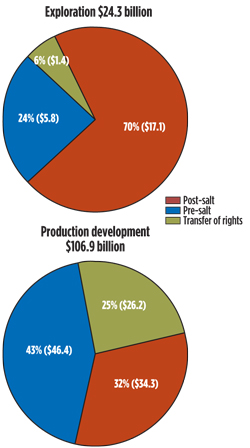

For the pre-salt round, slated for Oct. 21, the ANP is effectively offering the country’s largest offshore oil discovery in history, off the southeastern Brazilian coast. The entire round consists of the agency selling E&P rights for this single prospect, Libra, estimated to hold between 8 Bbbl and 12 Bbbl of recoverable crude oil. Libra is larger than Lula field, which lies to the southwest. It was Lula that triggered Brazil’s pre-salt frenzy in 2007.

“Today, the field produces 95,000 bopd from just four wells,” said Chambriard. “The estimated recoverable reserves at Lula are between 5 Bbbl and 8 Bbbl. But Libra is bigger—I’ve never seen anything similar to it.” Overall, she added, pre-salt production offshore Brazil is now 273,000 bopd and 8.9 MMm3/day. This compares to Brazil’s total oil output, which is now averaging 1.85 MMbopd. Chambriard said she believes that Libra’s incredible potential, based on 3D seismic data, justifies relatively stringent production sharing terms.

“The net pay of Libra is a 326.4-m column of 27°API oil,” she noted. “We are talking about wells that can produce 20,000 to 25,000 bpd—very high productivity.” Yet, potential participants will have to live with a governmental “take” of money from Libra’s production, which effectively equates to a rate of 75%. This rate is arrived at by adding the signature bonus, plus the government’s prescribed percentage of profits from production, along with the income tax paid on the remaining production by the participating firms.

Companies must also commit to a significant level of “local content,” even if those local equipment and service firms are not necessarily the most efficient or cheapest providers. Last, but not least, winning bids will be determined by the amount of oil from Libra that companies agree to hand over to the Brazilian regime. Previously, operators and partners developing Brazilian fields had paid royalties on production. All in all, the PSC terms appear likely to attract only the largest oil companies, with deep pockets and long timelines, including Chinese firms.

Meanwhile, ANP also will offer the 12th Bidding Round, consisting of 240 onshore blocks that focus on potential gas exploration in seven sedimentary basins. These blocks are strung across the states of Alagoas, Amazonas, Acre, Bahia, Goiás, Maranhão, Mato Grosso, Paraná, Piauí, São Paulo, Sergipe and Tocantins. They cover 168,348.42 sq km. Authorized by an executive resolution, the new round was just given final approval on Aug. 7, said Chambriard. In one section of the round, 110 blocks offered new frontier areas in the Acre, Paraná, Parecis and São Francisco basins. The idea is to attract investment into these relatively unknown areas, and to produce gas from both conventional and unconventional sources.

An additional 130 blocks are in the mature basins of Recôncavo and Sergipe-Alagoas, for which ANP is promoting natural gas E&P from conventional and unconventional sources. The 12th Round will feature the concession contract structure that was used for the 11th Round. “We believe that the possibilities for unconventional gas are analogous to the Barnett shale,” said Chambriard. “There are potential reserves of 30 Tcf of gas in 1,196 cu km of rock, at an average depth of 1,500 to 2,400 m.”

|

| Fig. 2. Regulatory obligations have given some investors cause for concern, when they consider the potential of Brazil’s Libra field. The discovery contains a 326.4-m column of 27°API oil, and reportedly could host wells that can produce 20,000 to 25,000 bpd (map courtesy of ANP). |

|

According to analysts at IHS Global Insight, who were quoted by The Wall Street Journal, Brazil’s Libra oil field (Fig. 2) may be the world’s most expensive to develop: “The total cost of developing the giant Libra field over the next 35 years could be at least $174 billion, making it the most expensive, single oil field project ever developed—more than Kashagan field in the Caspian Sea, which is expected to cost at least $150 billion.”

Despite the expenses and risks, some simple math suggests that the cost of extracting each barrel from Libra would be about $15, making it cheaper to develop than other recent discoveries off Africa’s west coast or in the Gulf of Mexico, where the range is between $22 and $30/bbl. With oil prices hovering above $100/bbl, the potential profits may be worth the risks. As Ruaraidh Montgomery of consulting group, Wood Mackenzie, told The Wall Street Journal, “That’s perfectly reasonable on a per-bbl basis, and certainly comparable with existing pre-salt developments in Brazil.

The industrial sector that supplies goods and services to upstream operators has mixed feelings (cautiousness and optimism) regarding regulations for the first production-sharing, pre-salt auction. The shipyards are optimistic about the possibility that Libra will bring jobs to naval construction in a horizon beyond 2020, Fig. 3. But other sectors, such as machinery and electrical/electronics, believe that it will be necessary to wait for the definition of the financing projects for platforms and rigs that will be used in this mega-field, to know whether domestic industry will have larger participation in Libra’s development.

|

| Fig. 3. Brazilian shipyards are hopeful that further exploitation of pre-salt resources will result in a greater number of construction projects and jobs at home. This contrasts with the recent farming out of projects to China and elsewhere, like the conversion of a tanker into the P 63 FPSO (photo courtesy of Petrobras). |

|

“We hope to increase the participation of electro-electronic industry in the projects of the concession, but also in production sharing,” said Paulo Sergio Galvão, coordinator of the oil and gas area of the powerful Brazilian Association of Electric-Electronic Industries (ABINEE). He said that the sector supplies five system types used for the oil and gas: automation, instrumentation and control, fiscal measurement, electric systems, and telecommunications. “However, up to now, we have supplied little in relation to the total value of the projects, because the local content estimates have been made on top of the total value of the projects. For example, in the case of a platform, the participation of the sector is 2% to 3% of the total value.”

Some lawyers specializing in oil and gas see obstacles affecting the attractiveness of the Libra auction for a large number of international oil companies. Some of the most criticized points are the lack of possibility to recover investments in the short term, and the mandating of local content rates. Thirty-seven percent of a project's needs must be procured locally during a project’s exploration phase. During the development phase, the amount of local content that must go into such work rises to 55%. ANP admits to a deficit in the availability of locally-produced drilling rigs and equipment, but says that Brazil's subsea technology has advanced to the point that the nation is seriously considering moving toward exporting some equipment.

According to estimates by the Brazilian Center for Infrastructure (CBIE), if one considers inflation at 6% per year, a little below the government’s forecast, during the next four years, 30% of initial investment made to begin producing petroleum will not be readjusted. This is because the government will only allow recovery of 50% in the first two years, and 30% of the costs in the following years. These numbers worry foreign oil companies.

Tight deadlines and long timeframes for investment returns, in addition to the risks that the oil will not be totally recoverable and that contracts cannot be extended, are other factors that industry experts have criticized. João Carlos França de Luca, chairman of Barra Energia, and also president of the Brazilian Petroleum, Gas and Biofuels Institute (IBP), is also not pleased with the minimum exploratory requirement of 40 years, which is part of Libra’s regulatory structure. His criticisms carry great weight, given his solid reputation within the industry, dating back to his 24 years as a manger/director within Petrobras, as well as his tenure as president of Repsol/YPF’s Brazilian unit from 1998 to 2009. According to the contract, the winning bidder must present a financial guarantee of some $300 million to undertake the minimal exploration program, which includes acquiring 3D seismic, drilling two wells and conducting long-duration production tests.

In response to his and other people’s criticisms, Chambriard said that much of the preparatory and exploration work has been completed, lowering the risks for prospective bidders. One of Libra’s additional attractions, she said, is its proximity to other fields/plays, including Lula, and the potential synergies that this could generate for project participants. The first productive pre-salt field, Lula, was discovered in 2006 and began producing oil in 2010, holding an estimated 8 billion bbl.

“This is something that is very unusual in the whole world, because we don’t have any notes about any other country offering such an opportunity [that is] already drilled, already discovered, already tested,” said Chambriard. “We tested the well that discovered the Libra area. From this well, we got a net pay of 326 m (1,070 ft).” The well flowed 3,667 bpd of 27°API oil during a first test, and 1,057 bpd in a second test, said Chambriard, later adding that the well could be a good producer, yielding 25,000 bpd to 30,000 bpd, easily.

|

| Fig. 4. Contributing to Lula field’s pre-salt output is the Cidade de Paraty FPSO, which officially went on production on June 10, 2013, and can process up to 120,000 bopd (photo courtesy of Petrobras). |

|

As of April 2013, pre-salt production averaged 295,000 bopd and 350 MMcfgd, with the greatest amount coming from four wells in Lula field, Fig. 4. Ramping up production at Libra is a crucial part of a broader plan to double Brazilian production by 2020, through the development of its pre-salt region.

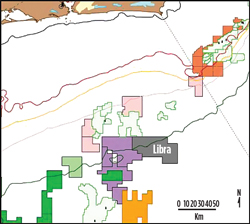

In fact, Petrobras, in its 2013-2017 Business and Management Plan, put projected investment in exploration activity at $24.3 billion, while expecting production and development investment to near $106.9 billion. The company accounted for post-salt, pre-salt and transfer of rights holdings in its plan for the next four years, Fig. 5. It also placed E&P infrastructure investments, outside of E&P development, at roughly $16.3 billion.

|

| Fig. 5. Petrobras estimates that nearly $24.3 billion will be spent on exploration activity from 2013-2017, while investments in production and development are projected to reach $106.9 billion. |

|

Petrobras, which is responsible for some 95% of Brazil’s oil output, expects to increase its production 110% and produce 4.2 MMbopd by 2020, while world petroleum production is expected to grow 10% by that year. The comparison, based on data from Wood Mackenzie, is backed up by statements from Petrobras President Maria das Graças Foster. Proven reserves of oil and natural gas held by Petrobras in Brazil are also expected to double during the same period. In 2012, the firm’s Brazilian reserves amounted to 15.7 Bboe.

In just 14 months (from January 2012 through February 2013), Petrobras reported 53 new oil and gas discoveries, including 15 in the pre-salt, said ANP. According to Petrobras’ Foster, the company during this period achieved an 82% exploratory success rate in the pre-salt. The global average is 35%.

Although Petrobras dominates Brazil’s oil and gas industry, private companies that operate in the sector, most of which are foreign, exported $5.7 billion in crude last year, equal to 20% of all oil exported. While Petrobras reduced its foreign sales by 3.5%, these foreign companies increased their sales 38%, on average. Nevertheless, of the $27.8 billion generated by exports last year, $22.1 billion were exports by Petrobras.

The participation of foreign companies continues to grow. At the end of 2012, BG Brasil’s average production was 28,000 bopd. This year, that figure hovers around 39,000 bopd. In total, foreign companies are producing around 200,000 bopd in the pre-salt.

|

| Fig. 6. Production activity from the Espirito Santo FPSO, at the offshore Parque das Conchas field, contributed to Shell becoming the largest exporter among foreign companies in Brazil in 2012 (photo courtesy of Shell). |

|

According to data from Brazil’s Ministry of Development, Industry and Foreign Trade, Shell was the largest exporter among foreign companies during 2012, totaling $1.4 billion, an increase of 34% compared to 2011, Fig. 6. However, four companies tripled foreign sales—Statoil ($1.2 billion), Sinochem ($808 million), BG Brasil ($667 million) and GE Oil & Gas ($292 million). So, how does one explain the advance in private participation? Analysts attribute it to the increase in domestic demand for oil products, which has caused Petrobras to refine more crude, thereby lowering exports. At the same time, Petrobras’ petroleum output went through a period of stagnation, while foreign companies, which also began to buy into pre-salt blocks during 2008, were beginning to produce, said Adriano Pires, director of the Brazilian Center for Infrastructure, CBI. Private companies are, therefore, exporting a growing share of petroleum produced in the country, encouraged by the difference in prices between the domestic and international markets.

|

| Fig. 7. At the Port of Santos, Petrobras will have a new logistical base ready next year. The firm will also construct a technological research center, as well as a technical school (photo courtesy of Porto de Santos). |

|

In 2014, at the Port of Santos (Fig. 7), Petrobras will have a logistical base to supply exploration of the offshore Santos basin, home to the largest pre-salt frontier. According to Santos City Hall, Petrobras will also invest, initially, around $38 million to construct a technological research center for petroleum and gas in the Santos area. By the end of the year, a tender will be published for the construction of two docks at the port, to serve the basin. To be operated by the winning bidder, the structure is forecast to be operational in first-half 2014.

Work will begin in the first quarter, in a 30,000-sq-m area, ceded by Santos City Hall. The complex also will have a technical school for the oil and gas sector. At present, offshore platforms are served by installations in Rio de Janeiro, and from the airport at Itanhaem, in São Paulo state. But, as nationwide output continues to increase, Petrobras needs new installations. Petrobras officials said that their business model of contracting services from third parties, at Santos and elsewhere, yields the best results for the company.

PRE-SALT’S BRILLIANT FUTURE

A study produced by BP, and entitled, “Outlook 2030,” predicts that Brazil will be one of three countries registering the largest increases in petroleum and biofuels (ethanol) production worldwide, behind only the U.S. and Canada. The increase in Brazil’s production is expected to be 2.7 MMbopd, of which 2 MMbopd will come from ultra-deep waters in the pre-salt. This would double the present production, which is nearly 2 million bopd. The country would, thus, produce 5.3 MMbpd by 2030. Of that latter figure, 4.1 MMbpd will be petroleum, and 1.2 MMbpd will be biofuels. According to the same study, Brazil will become an important exporter of liquids (petroleum and ethanol), averaging 1.2 MMbpd. BP’s projections may be considered conservative, as Petrobras, itself, forecasts production of 4.2 MMbpd of petroleum by 2020.

Meanwhile, Petrobras President Foster compared Brazil’s energy matrix to that of the world, using numbers and projections from the International Energy Agency (IEA), utilizing consolidated data from 2010. She argued that 81% of the global energy mix comes from fossil fuels, such as petroleum, coal and natural gas. However, in Brazil, these fuels represent just 53% of the mix. Projections for 2030 indicate that, globally, the demand for energy met by fossil fuels will represent 77% of the total, whereas it will only be 52% in Brazil.

In the transportation sector, petroleum represents an even greater share of the world mix, totaling 93% in 2010. That figure will decrease, only slightly, to 88% by 2030. In that period, the share held by natural gas is expected to go from 4% to 5%, and biofuels will go from 2% to 5.5%.

Considering this scenario, Foster explained that it is necessary to invest significantly in the search for additional petroleum supplies, since the timeline to reach production is long. “For example, when a deepwater basin begins to be explored, 10 years are needed to recover first oil,” she said. “The development of production takes even more time,” affirmed Foster, reminding her audience that, to begin production today, the company anticipates what demand will be for first oil, at least 10 years ahead, and then what it will be for another 10 to 20 years during the entire concession period. Finally, Foster noted that the break-even production price point needed to recover investment in the pre-salt, considering all the costs and investments (excluding infrastructure), is between $40 and $45/bbl. That figure, she said, is below the cost of several fields under development elsewhere in the world.

|