STEVEN KOPITS, Douglas-Westwood

|

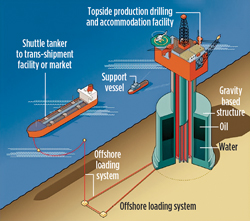

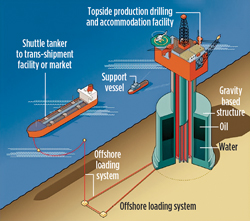

| Prirazlomnoye oil platform, in the Pechora Sea, south of Novaya Zemlya, Russia (left). The gravity-based platform is 60 km offshore at a water depth of 66 ft, with a field resource in excess of 500 MMbbl. The Polar Pioneer drilling rig at Skrugard (now Johan Castberg) field in the Barents Sea for Statoil. Photo credit: Harald Pettersen (center). Moncla jackup rig drilling for Hilcorp Energy in Alaska’s Cook Inlet. |

|

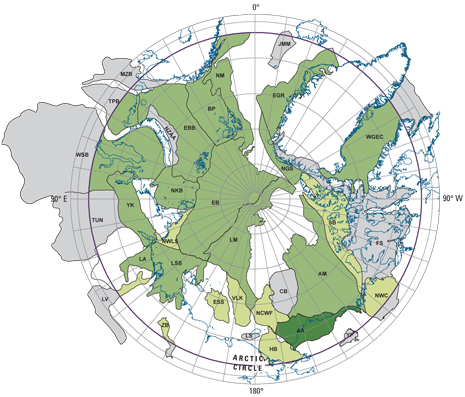

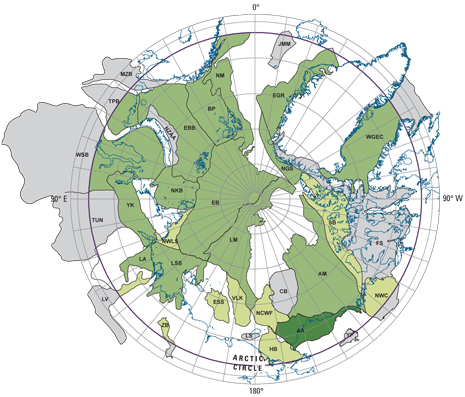

Articles about the Arctic inevitably extol its virtues, citing estimates from the U.S. Geological Survey of more than 400 Bbbl of technically recoverable resources in the ice-bound region, Fig. 1. Close to 85% of these resources are estimated to be offshore, and thought to be principally gas. The Arctic is the last frontier, and soon, very soon we are told, the oil and gas industry will benefit hugely from its development. Some of this is undoubtedly true. Exxon Mobil and Shell have huge investments on Russia’s Sakhalin Island, and a number of operators have achieved success investing in Canada’s Atlantic waters offshore Nova Scotia and Newfoundland. But, elsewhere, the challenges loom larger. In Canada’s Northwest Territories, the offshore region is ostensibly open for exploration, but the conditions are sufficiently onerous that operators are uninterested. In Greenland, the new government has restricted the issuance of new offshore leases, and no one has yet demonstrated that Greenland has commercial potential. In Norway, Statoil postponed the Johan Castberg (Skrugard) development following tax hikes there. But nowhere is the situation more acute than in Alaska, where a combination of changing industry economics, a conflicted voter base, and an unhelpful U.S. administration are conspiring to strand a resource with comparable potential to the Gulf of Mexico.

|

| Fig. 1. USGS map showing provinces in the circum-arctic resource appraisal (CARA) color-coded for mean estimated undiscovered oil in oil fields. The dark green areas are expected to have resource potential of greater than 10 Bbbl. Operators are drawn by the USGS 2008 resource potential estimate of 90 Bbbl of oil, 1,669 Tcf of natural gas, and 44 Bbbl of natural gas liquids. |

|

The Arctic holds great promise, but increasingly, the risk is that it remains just so. Doubts are gathering about whether governmental policy, combined with changing industry economics, will permit the development of the last frontier. We will turn to this question in due course, but first let’s take a look at the Arctic, country by country.

THE U.S.–ALASKA

Alaskan oil production peaked in 1988 at around 2 MMbpd and has been falling since, possibly down to 510 Mbpd in 2013. Virtually all of this production flows through the 800-mi Trans-Alaska Pipeline (TAPS), to Valdez, in southern Alaska. But TAPS is struggling, operating below a quarter of its capacity, with fears that it will lose its viability below 300 Mbpd.

In the wake of the run-up in crude oil prices before the recession, then-Gov. Sarah Palin (Rep.) implemented a 75% tax rate from 2007. This stalled investment, and production decline rates increased to nearly 7% from 4% a decade earlier. Alarmed by the decline, the current governor, Sean Parnell (Rep.), reduced the top tax rate to 35%. This action brought promises of investment by BP and ConocoPhillips, and clear signs of increased industry activity. However, expectations remain modest, at best, to reduce declines to 20 Mbpd/year from the current 40-Mbpd pace. If expectations are met, TAPS will reach the 300 Mbpd threshold in 2024, rather than 2020. Many Alaskans are unimpressed and are forcing a referendum to re-instate the higher tax rates—they see the end of the state’s golden age of oil and want to get all they can, while they can.

On the other hand, Shell has big plans, to produce as much as 1.8 Mbpd from Alaska’s Outer Continental Shelf, 40% more than the Gulf of Mexico production rate today. But the cost to first oil is in the $40–60 billion range, and one has to wonder whether Shell has the fortitude to hold out until initial production in 2025., Fig. 2.

|

| Fig. 2. Shell’s Arctic exploration projects offshore Alaska are on hold since the grounding of the Kulluk drilling platform on the southeastern shore of Sitkalidak Island. Shell plans to scrap the Kulluk and resurrect its Arctic plans in 2014. |

|

Indeed, Goldman Sachs spent much of a recent report berating Shell for “overspending in low-return assets and unproductive capital.” Shell’s incoming CEO, Ben van Beurden, comes from the chemicals division, where he managed to increase profitability and lower Capex. Will a downstream manager feel the exotic lure of Alaska as much as the upstream team has? Or will he decide that 2025 is just too long for investors, who are looking for cash quarter by quarter? Alaskans have good cause to feel nervous.

CANADA

Canada’s Arctic fields are considered to include its Atlantic fields offshore Newfoundland and Nova Scotia, as well as the McKenzie River Valley and the Canadian Beaufort Sea in the Northwest Territories. Technically speaking, Canada’s Atlantic fields are sub-Arctic, but they share many commonalities with Arctic plays, notably, remoteness, winter cold and darkness, and perhaps most importantly, chronic iceberg risk. Thus, the Atlantic fields tend to have Arctic characteristics, even if they are south of the Arctic Circle, geographically speaking.

These Atlantic fields are well-developed, with three key projects representing effectively all oil output. Hibernia was brought on-line in 1997 in an 80-m water depth, using the world’s largest gravity-based platform. Terra Nova initiated production in 2002, and White Rose saw first oil in 2005. Collectively, these three fields have reserves of 1.4 Bbbl. Terra Nova recently saw its reserves revised upwards, with future production estimated to last seven years beyond earlier expectations, to 2027. In addition, Exxon Mobil is on track to bring the Hebron facility online in 2017, with reserves estimated in the 400-700-MMbbl range, Fig. 3. The Atlantic fields produced about 200 Mbpd in 2012, down 26% from the previous year, primarily due to maintenance issues. Production from these fields, while steady, is increasingly modest in comparison to oil production from Canada’s western provinces: Canada’s oil sands will add about as much production per year as the Atlantic fields’ total output.

|

| Fig. 3. Exxon Mobil plans to develop Hebron field offshore Canada to produce 150,000 bpd of heavy oil by 2017, at a cost of $14 billion. |

|

The Atlantic fields also produce substantial quantities of gas. The Sable Offshore Energy Project off the coast of Nova Scotia produces 200 MMcfd, but it is anticipated to be depleted within the next five years, after which Exxon Mobil intends to decommission the unit. A new development, Deep Panuke, missed its most recent June 2013 deadline, but it is expected to start up within the next year. Decreasing production from Sable and Panuke’s delay caused Halifax province’s offshore royalties to decline to $28 million in 2013, down from a peak of $451 million in 2009.

In late September, Statoil and partner Husky Energy announced that their first Bay du Nord exploration well has discovered between 300 and 600 MMbbl of recoverable resources. The Bay du Nord discovery is Statoil’s third discovery in the Flemish Pass basin. The Mizzen discovery is estimated to hold a total of 100–200 MMbbl of resources. The Harpoon discovery, announced in June, is still under evaluation. According to Statoil, the Bay du Nord well encountered light oil of 34° API, and excellent Jurassic reservoirs with high porosity and high permeability. There are hopes for new projects in the future. BP and Shell have secured additional leases in the area, but exploratory drilling still appears to be a few years away.

In the northwest of the country, the McKenzie Valley pipeline project is most often discussed. This would bring natural gas from the Northwest Territories to Canadian and U.S. markets. However, the economics of the project are not feasible under the low gas prices prevailing in North America presently, and the project is on hold, with Shell looking to dispose of its interest in the project.

Canada’s Beaufort Sea represents an area the size of the Gulf of Mexico and is thought to contain substantial oil resources. Regulations regarding exploration and development drilling there came under review by Canada’s National Energy Board following the Macondo blowout. The resulting Arctic Offshore Drilling Review required 18 months and led to a considerable tightening of regulations, which appear to have been developed with light regard for the economics of development in Canada’s Beaufort. This showed in the leasing round following the issuance of revised regulations. Canada’s largest-ever oil lease in the Arctic —2.2 million acres—was awarded to Franklin Petroleum Limited (UK) for $7.5 million in 2012. Franklin had only two employees, a net worth of negative $32,000, with a CEO who had never worked in the Arctic. The oil majors stayed away. It is hard to describe lease results as anything but humiliating for the Canadian government, reflecting a complete misunderstanding of industry dynamics. On the other hand, not a few in the industry felt that the purpose of the Arctic Review was to provide the veneer that Canada’s Beaufort was open for business, when it was closed as a practical matter. If this is true, then the Canadian government can consider its Arctic policy a success; and indeed, when considered jointly with Alaska’s prospects, Canadians have good cause to think the Canadian Arctic will never be developed commercially.

GREENLAND

With the run up in oil prices after 2005, a number of countries were prompted to try to cash in the on the oil bonanza. Lightly populated Greenland was among them. Across the Labrador Sea, Canada’s eastern fields had proved a motor for the economies of Newfoundland and Nova Scotia for years. Perhaps this model could be imported to Greenland. With that, the government there began to lease tracts, primarily on the southwestern side of Greenland. To date, 20 licenses have been issued to companies, including Shell, Statoil and Moller-Maersk. But none was more enthusiastic for the region than Cairn Energy. The UK-based explorer drilled eight wells in 2010 and 2011, spending $1.2 billion in the process, but failing to strike oil. The company, backed by Norway’s Statoil, hopes to return to drill the Pitu prospect next year, which Cairn believes could contain 3 Bbbl of oil.

Greenland’s drilling politics have become more challenging, with the election earlier in the year of the social democratic Siumut party, which bested the ruling socialist Inuit Ataqatigiit party in elections in the spring. Jens-Erik Kirkegaard, Greenland’s new minister for natural resources, at first stated that the 20 licenses issued to date would be the maximum, but later clarified the matter by stating that more licenses will be issued, including licenses for new areas, once current licenses are turned in. This process is likely to begin in the next year.

Drilling in Greenland may yet have a future, but Cairn’s notable lack of exploration success and the government’s visible ambivalence must surely dampen industry enthusiasm for committing incremental resources to the country.

NORWAY

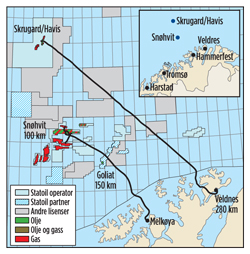

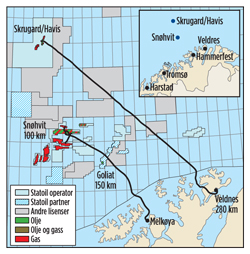

Norway is, to an extent, an exceptional case, in that it is a small, wealthy and environmentally aware country accustomed to cold, indeed Arctic, conditions. Thus, while drilling in the Alaskan Outer Continental Shelf constitutes something novel (although, in fact, not new at all), Statoil and other operators have been active in the Arctic portion of the Norway for many years. The principle development in the Norwegian Arctic is Snøhvit, the first offshore development in the Barents Sea. Unusually, the project operates without surface installations, producing natural gas using only a subsea production system. This gas is transported to land via a 143-km pipeline, liquefied onshore, and transported via LNG tankers to European markets. Eni’s Goliat field, also in the North Barents Sea and 85 km from Hammerfest, is scheduled to come on-line in 2014, employing a circular Sevan FPSO. The produced oil will be transported from the FPSO by shuttle tankers, Fig. 4.

|

| Fig. 4. Barents Sea oil and gas fields under development include Snøhvit, Goliat (offshore Norway) and Skrugard/Havis (now Johan Castberg). |

|

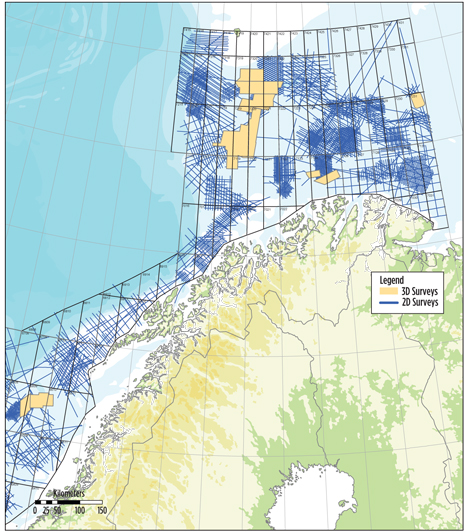

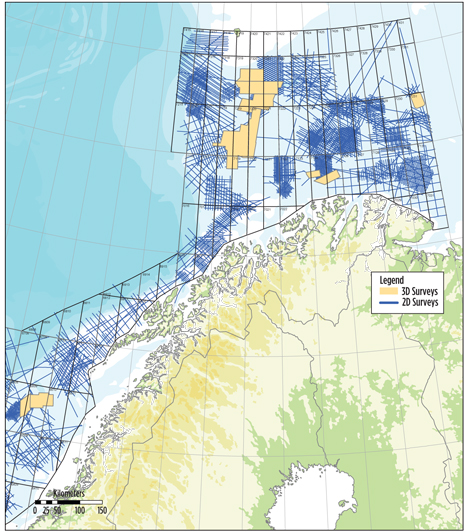

Norway’s other Arctic prospects are also clustered in this general region, Fig. 5. Statoil’s Johan Castberg project lies about 100 km north of Snøhvit field, and consists of the Skrugard and Havis discoveries, which are estimated to contain, together, 400 to 600 MMboe. The project was returned for reconsideration following the Norwegian government’s announcement of increased taxes on oil and gas activities. Statoil also cited uncertainties about resource estimates as a factor driving re-evaluation. Attention is now turning to the region north of Skrugard, known as the Hoop Area. The region abuts Norway’s Arctic borders, with the UK and Russia potentially contesting finds there. Expect the Norwegians, pragmatic and skilled diplomats, to resolve the issue.

|

| Fig. 5. Multi–client 2D and 3D seismic data acquired by WesternGeco in the Norwegian Arctic. |

|

Cost overruns have plagued Norway’s Arctic projects. Eni’s Goliat field development costs increased 8% just last year, and are now 25% above the original budget level. Nor have sub-Arctic projects been spared, with the Skarv project 31% over budget, and BP’s Valhall redevelopment nearly 100% over original estimates. Such cost overruns are by no means unique to Norwegian projects, but the complexity and technical demands of operating in ever-more-remote and harsh environments continues to increase the cost of drilling and production. Norway is especially exposed to these trends.

RUSSIA

Russia’s Arctic plays fall into three broad regions: the northern Barents Sea; north-central Russia, including the Kara and Pechora Seas; and Russia’s Far East, notably Sakhalin Island.

The recent hot topic in Russia is the newly inaugurated Prirazlomnoye oil platform, in the Pechora Sea, south of Novaya Zemlya, Russia. The gravity-based platform is 60 km offshore at a water depth of 66 ft, with a field resource in excess of 500 MMbbl. The platform is able to resist strong ice loads and offers year-round operability. Plans call for 40 slanted wells to be drilled from the platform. Initial production is scheduled for late 2013, with peak output slated for 130 Mbopd.

The project has been a long time coming. The field was discovered in 1989. In 1993, Rosshelf, a subsidiary of Gazprom, was awarded a development license with the intent that the field would be operational by 2001. The project changed hands a number of times, eventually being transferred to Sevmorneftegaz, now a subsidiary of Gazprom. From development award to first oil required 20 years, demonstrating the challenges of operating in the Arctic.

Prirazlomnoye is the first truly Arctic platform (those in Canada and at Sakhalin Island are technically in sub-Arctic waters). Gazprom intends to use the platform for tiebacks from later field developments, notably the nearby Dolginskoye oil field. The field is served by two, “double-acting” shuttle tankers, Mikhail Ulyanov and Kirill Lavrov, transporting oil to the Belokamenka, an FSO vessel located in Kola Bay near Murmansk. Double-acting tankers also function as light ice breakers, and can sail in either direction, allowing them to back out of ice-filled areas.

The Prirazlomnye project recently drew attention, when a team from Greenpeace attempted to board the platform to bring attention to their perceived lack of safety awareness and response capability by the platform. Greenpeace members were arrested.

Yamal and Gydan peninsulas. Some 1,500 mi northeast of Moscow, the Yamal and adjacent Gydan peninsulas extend into the Kara Sea and are endowed with vast gas reserves. A variety of producers are looking to monetize these resources via liquefaction. Perhaps most notable is the JSC Yamal LNG project. The partners include Russia’s Novatek, Total and, more recently, China’s CNPC. The consortium plans to build an LNG plant with three LNG trains and a capacity of 15 mtpa. The cost is projected at $15 billion, with phased train commissioning in 2016, 2017 and 2018. Technip has been chosen as EPC and GE is providing associated turbomachinery, with equipment delivery scheduled for second-half 2015. In theory, continued shrinkage of Arctic sea ice may enable use of the northern sea route to ship Yamal LNG 7,500 mi to China, or 2,000 mi to Western Europe. It is not entirely clear why a western European customer would prefer Arctic Russian LNG, which requires transport across a potentially frozen Arctic using ice-class LNG carriers, when cheap U.S. shale gas will be available, with less complex infrastructure and logistics. Nor is it clear that the Bering Strait will be ice-free when the Chinese start demanding LNG imports. Finally, Gazprom holds a monopoly of the export of gas from Russia, and the Yamal LNG project would require a waiver to be able to access foreign customers. Russian President Vladmir Putin appears to support such waivers, which may be granted early next year.

Another important development has been the agreement between Rosneft and Exxon Mobil for a joint exploration and production effort in the Kara and Black Seas. Under terms of the deal, Exxon Mobil and Rosneft would seek to develop three fields in the Arctic, with recoverable hydrocarbon reserves estimated at 85 Bboe. Rosneft is to have a two-thirds stake in the venture, while Exxon Mobil would own a third and shoulder the initial exploration costs. Exxon Mobil has outlined an initiative to jointly commit $3.2 billion to exploring the Kara Sea and Black Sea. A final investment decision on the projects in the Kara Sea has been slated for 2016–17. If the reserve base is confirmed, Rosneft sees total investments in excess of $500 billion in the coming decades. Given the historical realities of doing business in Russia, this may represent the triumph of hope over experience, but clearly, the upside potential is substantial.

Shtokman. The giant Shtokman gas field, in the north Barents Sea, used to be one of the mainstays of discussion of Russian Arctic projects. The field lies 370 mi north of Kola Peninsula, with reserves estimated at 3.8 Tcf of natural gas and more than 37 MMt of gas condensate. The field was discovered in 1998, with a revolving cast of characters emerging as potential partners in project development in the interim. The latest incarnation includes Statoil, Total and Russia’s Gazprom. Breakeven costs were estimated at $14/MMbtu, a shockingly high number considering that U.S. shale gas is priced at under $4/MMbtu. In late 2012, the project was put on hold. It is unlikely to be revived until U.S. domestic gas prices rise well above recent levels.

Sakhalin. Located in Russia’s Far East, Sakhalin Island is an important source of both oil and gas. Two major consortia produce oil and gas there. The Sakhalin-I consortium was created to produce oil and gas from Chayvo, Odoptu and Arkutun-Dagi fields in the Okhotsk Sea. The group is operated by Exxon Neftegas Limited (ENL), with partners Rosneft, Japan’s SODECO, and India’s ONGC. Chayvo field was identified as holding potential hydrocarbon reserves in 1979, and production began there in 2005. Odoptu field came on line in 2010, setting the record for the longest horizontal reach by a well in the process. In 2012, the consortium completed and installed Berkut, a gravity-based platform for Arkutun-Dagi field, offshore northeastern Sakhalin, in the process breaking its own record for the longest horizontal well in the world. Sakhalin I has produced oil at a 250-Mbpd pace.

The Arkutun-Dagi field development will help maintain production by offsetting natural declines at Chayvo field. First oil from Berkut is expected in 2014. The consortium is also planning to add an LNG facility for the project. Gazprom had wanted to buy up gas production from Sakhalin-1 to supply Russia’s Far East. Negotiations, however, appear to have foundered on price, and the Sakhalin-I consortium now plans its own $15-billion LNG facility to supply the Asia-Pacific region. Rosneft and Exxon Mobil have awarded separate front-end engineering and design study contracts for the facility to engineering firms CB&I and Foster Wheeler. The work will be split in two phases, with the contractors to produce conceptual designs for the proposed plant before the end of 2014. After the first phase is complete, Rosneft will score the results and then award a contract for the second phase.

Sakhalin II was originally a consortium of Shell, Mitsui and Mitsubishi, formed in 1994, to develop Piltun-Astokhskoye and Lunskoye fields on the northeastern shelf of the Sakhalin Island. Phase I of the project was launched in 1994, with first oil achieved in 1996 from Piltun-Astokhskoye oil field. Phase II was launched in 2003. In 2007, at the Russian government’s insistence, the consortium was expanded to include Gazprom, with that company eventually coming to own a majority stake. Sakhalin II recoverable hydrocarbon reserves are estimated at 600 Bcm of gas and 170 MMt of oil and condensate. An associated LNG facility, the only one in Russia, was commissioned in 2009 and exports LNG, primarily to Korea. The existing LNG plant has reached full capacity, and in fact, in 2012, exceeded its annual design output of 10 mtpa by 9%. Gazprom plans to expand existing Sakhalin II capacity by building a new LNG plant on the Russian Pacific coast near Vladivostok, although questions have arisen regarding the resource base to support such an expansion.

The Sakhalin III project is intended to augment the island’s gas supply. Gazprom holds licenses for three blocks within the project, including Kirinsky, Ayashsky and Vostochno-Odoptinsky fields, and the Kirinskoye gas and condensate field. Kirinskoye will be the first offshore field in Russia to utilize a subsea system for natural gas production, with FMC as the hardware vendor. The field is 28 km offshore of Sakhalin Island, in the Kirinsky Block of the Sea of Okhotsk, at a depth of 90 m. The field was discovered in 1992, and contains reserves of up to 137 Bcm of gas and 15.9 MMt of retrievable condensate. Six wells are expected to be drilled from the project site. Gas extracted from the wells will be transported through a 28-km pipeline for onshore processing, with the treated gas transferred through a 139-km pipeline to an LNG plant and eventual export. Gazprom expects production to begin toward the end of 2013.

ARCTIC DEVELOPMENT PROSPECTS

The oil majors see their economics increasingly challenged. In the spring of 2013, Elliott Management, an aggressive hedge fund, acquired shares in Hess Corporation, with the intent to improve financial performance.

This led to Hess’s commitment to divest its refineries and filling stations, and to materially restructure its upstream portfolio. It was not lost on the industry that a financial investor had brought a member of the oil fraternity to heel. With this, the notion that oil companies would grow forever was buried.

The oil majors were not unfamiliar with the thesis—ConocoPhillips had been divesting its assets for the last few years—but, it cemented the belief that growth would not save the oil majors. Oil prices would not rise quickly enough to cover rapidly escalating E&P costs and ballooning Capex budgets. Matters came to a head with the industry’s disastrous financials for second-quarter 2013. In response, Shell CEO Peter Voser stated that Shell would no longer provide forward production guidance and rather focus on increased cash flow generation.

For the industry, this is an enormous change in strategy. An industry which prided itself on the long view, on projects—like Alaska—which could require 20 years to bring to fruition, would now be looking for quarterly cash flow enhancement. The model of stewardship, in which managers made decisions for their companies which would outlive their own or colleagues’ careers, was over.

For the Arctic, this change in approach is potentially devastating. In a late September interview, Voser expressed uncertainty about whether Shell would return to Alaska in 2014 or 2015. Moreover, Shell’s incoming CEO made his name in the chemicals division by cutting Capex and increasing profitability. It is hard to see how Alaska escapes this new reality of cash over production growth.

Norway may remain a little better for a while longer. The Norwegian government has a major stake in Statoil, the country’s leading oil company. But even here, the stress is visible. When the Norwegian government announced tax increases on the oil industry, Statoil promptly deferred its Johan Castberg project in the northeast Barents Sea. Statoil continues to invest heavily—one of the few international oil companies with plans to ramp up Capex—but the company sees its future outside Norway.

Be that as it may, the economics weighing on the other oil majors are weighing on Statoil as well, and within a finite space of time, Statoil Capex trends will come to reflect its peer group. Norway is heavily exposed to the cost pressures descending on the industry: a declining oil resource, pressures to move to ever-more-remote and harsher environments, one of the world’s most expensive labor forces, and a high-cost industry leveraged to Capex-heavy projects. Even as record amounts are invested in Norway this year, as backlogs top record highs and the industry runs flat out, the clouds are gathering. The very forces that have conspired to lift activities to such levels will also be their undoing.

Arctic oil and subsea processing are in demand because the easy oil has been found. As long as consumers were willing to underwrite elaborate technologies in remote places with higher oil prices, the trend line favored Norway. But consumers have reached their limits for increasing gasoline and diesel prices, even as oil will

continue to become more expensive to extract. These two factors will force Statoil from its Arctic perch, with the Johan Castberg deferral just a taste what is to come. Norwegian complacency may last a year or two more, but in a short time will transform into concern that Norway will, in its own way, follow the path of Nokia and Finland, where events simply bypassed the country. Whereas the Norwegian government in the past felt empowered to raise taxes on the oil industry, government take will be in retreat for the balance of the decade. To stimulate investment, taxes will be reduced on marginal or remote fields. These policies will work for a time, to be followed by a need to reduce taxes again. The Norwegian government will find itself in retreat from here on, trying to defend the industry which has elevated the country to the tops of the ranks in income and standard of living.

It is hard to know whether Russia will prove better or worse than Norway or Alaska. Russia still has sizeable conventional reserves that could be brought into service, were the government suitably motivated. Nor is the Russian Arctic as well-explored as the Norwegian shelf or the Alaskan OCS. The new Prirazlomnye platform creates a basis for further expansion in the Pechora Sea. This is, to an extent, also true for Sakhalin, although expansion there has been muted in recent years. Still, infrastructure is in place, and the region has ready access to Japanese and Korean markets, in particular. Russia can still see an upside.

Taken as a whole, however, prospects for Arctic development look increasingly endangered. Economics are moving against the industry, something that governments will be slow to recognize or welcome outright. Alaska and Norway can revel in the bright light of the oil’s late afternoon, but time is running against them.

|

Integrated ice management system reduces risk in Arctic seismic and drilling operations

The Arctic contains an estimated 25% of the world’s undiscovered hydrocarbon resources, but harsh, icy conditions pose operational hazards to E&P operators and seismic contractors. The Narwhal system from ION Geophysical is designed for gathering, monitoring and analyzing data from various sources, including satellite imagery, ice charts, radar, manual observations, and wind and ocean currents, to forecast weather and predict ice movements.

With the Narwhal system’s ability to track and forecast potential ice threats, operators can make informed, proactive decisions to ensure the safety of people, assets and the environment, while minimizing operational downtime. The system is named after a toothed whale that lives year-round in the Arctic.

“One aspect of Narwhal ‘s functionality is the way it manages ‘trafficability’—the ability to use all of the ice information to define go/no-go areas, plan routes, optimize vessel operations, and identify escape routes in multi-vessel and platform operations,” explained Des Flynn, Vice President of ION’s Concept Systems group, responsible for the development of Narwhal. “The system’s enterprise capability allows multiple vessels, platforms, and onshore operations to share and visualize all available information in a common operational picture, thereby improving efficiencies and providing the entire operation with greater situational awareness.”

The Narwhal system is currently in commercial use in the Canadian Northwest Passage and offshore Baffin Island.

|

|

The author

STEVEN KOPITS is the managing director of Douglas–Westwood LLC (USA). Since joining the firm in 2008, he has led dozens of projects on various oilfield technology and service topics. He has a background in strategic management consulting and investment banking. Mr. Kopits has assisted more than 100 companies in market analysis, business planning and related financial modeling throughout a range of industries, including energy, manufacturing, power and maritime shipping. He writes frequently on issues related to energy and the economy, and his work has appeared in a wide range of industry publications. |

|