Oil and gas in the capitals

A carbon tax of any kind would clobber the poor

|

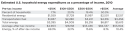

The carbon tax keeps reappearing as a policy option, no matter how often it is defeated. While its popularity with the Obama administration is hardly surprising, what is more troubling is its recent advocacy by some prominent Republicans, including Gregory Mankiw, George W. Bush’s chief economist, and Douglas Holtz-Eakin, senior advisor to John McCain’s 2008 presidential campaign. More ominously, in an April editorial in the Wall Street Journal, George Shultz and Gary Becker endorsed a carbon tax—the 82-year-old Becker is a Nobel laureate in economics, and the 92-year-old Shultz is a pillar of the Republican establishment, serving in top positions in Republican administrations from 1969 to 1989, including Secretary of State under President Reagan. So, what is going on here? Public opinion surveys indicate that U.S. voters overwhelmingly oppose such a tax; voters will penalize those attempting to implement any such tax. For example, in 1993, President Clinton proposed a “BTU tax” that was defeated. The following year, the Democrats lost control of the House of Representatives. In 2009, President Obama and the Democrat-controlled House attempted to enact cap-and-trade legislation—an ersatz carbon tax. The following year, the Republicans regained control of the House by a large margin. Thus, if insanity is defined as “doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results,” are both major U.S. political parties insane? No one disputes that a carbon tax will increase energy prices. While much can be said about carbon tax effects, there is a major deficiency that is too little-noted or discussed—it is one of the most highly regressive taxes. It is almost inconceivable that politicians and policymakers, who purport to be concerned with the economic plight of the impoverished and working poor, and with middle class struggles, would seriously advocate such a tax. A carbon tax would harm the less-affluent disproportionately—the less wealthy, the more harm. Energy cost increases are regressive, because expenditures for essentials, such as energy, consume larger shares of low-income budgets than they do for higher-income families. Whereas affluent families may trade off luxury goods to afford higher energy costs, low-income families do not have this option. Thus, when less-affluent families face rising energy costs, they must choose between paying for energy and other necessities, such as food, housing and health care. These are hard choices. The table on this page shows that less-wealthy households spend the largest shares of their income to pay for energy. The portion of U.S. household income spent on energy is increasing, especially for lower-income groups. Energy costs as a percentage of income increased 75% between 2001 and 2010, from a national average of 6% to 10.4%. However, for households earning under $10,000/year, the portion consumed by energy costs increased from 36% to 69%. In households earning $10,000 to $30,000/year, the income consumed increased from 14% to 22%. For households earning $30,000 to $50,000/year, the income required for energy increased from 10% to 16%. Finally, in households earning more than $50,000/year, the portion devoted to energy increased from 5% to 8%.

Thus, the poorest households pay, proportionately, nine times as much for energy as the most affluent households, and would be the most affected by a carbon tax. Even households earning $10,000 to $30,000/year pay, proportionately, three times as much as affluent households. Studies show that households, earning $50,000 or less, spend: more on energy than on food; twice as much on energy as on health care; more than twice as much on energy as on clothing; more on energy than on anything else, except housing; more than 1/4 of their income on housing; and have little discretionary income. High energy prices harm those with limited incomes, such that families unable to pay their bills face utility shut-offs that deprive them of heating, cooling, lights, refrigeration, and the ability to cook food. A recent survey found that numerous low-income respondents experienced a utility shut-off during the past year, due to rising costs. Being unable to afford energy bills is unhealthy, and people purchase less medicine when utility bills are high. High energy prices also compromise low-income household safety, and the inability to pay utility bills often leads to the use of risky alternatives. Households frequently try to save money by turning to electric space heaters, which are a major fire hazard. Families also incur housing risks. Shut-offs make homes uninhabitable, forcing residents into homelessness or alternative forms of shelter. Thus, a carbon tax would disproportionately harm the least affluent, most vulnerable members of society by directly and indirectly increasing energy costs. These impacts, alone, strongly argue against its implementation. |

||||||||||||||