IAN LEWIS, Contributing Editor

|

| Nearly half of the gas produced from Apache’s operations in Neuquen basin contributes to Argentina’s Gas Plus program, which targets development of “new gas” from undeveloped formations. |

|

Despite the abundance of unconventional oil and gas potential in all corners of the globe, North America remains the only region with a booming shale industry. However, a host of other countries are eager to emulate the region’s success and exploit their own, domestic shale resources.

GLOBAL OVERVIEW

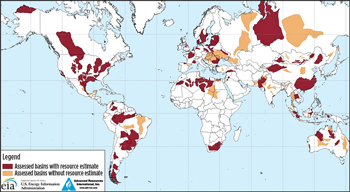

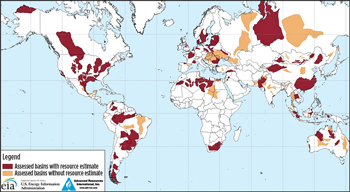

There is no doubt that the companies that have fared well in the maturing North American shale sector are eager to seek opportunities to repeat their success elsewhere; and there is no shortage of countries eager to emulate this same success at home. More than 90% of the world’s technically recoverable resources (TRRs) of shale gas—amounting to some 6,634 Tcf—lie outside the U.S. (Fig. 1), according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).

|

| Fig. 1. Basins with assessed shale oil and shale gas formations (source: U.S. basins from U.S. EIA and USGS; other basins from Advanced Resources International, based on data from various published studies). |

|

However, despite the fact that an abundance of resources is available, the global shale revolution is not to be hurried. While significant investments are being made in shale gas and oil exploration—in countries such as Argentina, Australia, China, the Ukraine and the UK—commercial-scale production has yet to occur, on a sustained basis, outside North America.

Many observers believe that it is only a matter of time before the shale sector takes off globally. Proponents argue that as technology and know-how spreads, service firms build up their global infrastructure, and conventional reserves mature, investment will start to flow into the global shale sector.

Others believe that the absence of a low-cost environment, of the type that triggered the U.S. boom, will stymie shale development. There is also an argument that if U.S. LNG exports, based on shale gas, come onstream soon, projects that would produce relatively expensive shale gas in other parts of the world will be deferred—in which case, the industry may come to be seen as a victim of its own success.

However, as usual, the reality is likely to lie somewhere in between, with shale projects taking off in some places and failing in others. Either way, the number of countries hoping to hit the jackpot is growing steadily.

LATIN AMERICA

The largest of Latin America’s shale gas reserves lie in Mexico, Argentina and Brazil; Argentina and Venezuela hold the bulk of the region’s shale oil deposits. Until recently, investment in shale development has been limited, due largely to uncertain investment conditions, bureaucratic hurdles, limited infrastructure and restricted markets. While Argentina is now making efforts to draw in investment, to exploit its vast shale reserves, for others it is less of a priority. In countries such as Brazil and Mexico, the governments prefer to target conventional reserves.

Argentina. The attraction of the world’s second-largest shale gas reserves (TRR of 802 Tcf, according to the EIA) and fourth-largest shale oil resources (27 Bbbl) has pulled foreign investment into the sector. This is despite the uncertainties caused by the government’s expropriation of Repsol’s 51% stake in Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales (YPF—a company which was state-controlled prior to 1993 and is so again, now).

In July, YPF finalized its first agreement since renationalization, when Chevron signed up to develop the shale oil and gas reserves of the Vaca Muerta—the country’s largest shale formation—in the western province of Nequén. Chevron is to make an initial investment worth $1.24 billion, with the possibility of raising that to $15 billion, if exploration merits such expenditure. Initial activity will involve drilling more than 100 wells on a 5,000-acre tract, which is part of a 96,000-acre concession.

This agreement was followed up by a deal with Dow Chemical in September, under which Dow’s Argentine unit will invest $120 million a year, and YPF will invest $68 million a year in drilling 16 shale gas wells, in the Vaca Muerta.

China National Offshore Oil Corp. (CNOOC) is also believed to be nearing an agreement to explore and develop Vaca Muerta acreage, possibly through Bridas Group, its existing joint venture with two brothers, Carlos and Alejandro Bulgheroni.

Several international firms have been operating in the Nequén basin, and elsewhere in the country, for several years. These include Apache Corp., EOG, Exxon Mobil, Total and Chevron. However, developments have progressed at a snail’s pace, due to a lack of investment, poor prospective returns, red tape and political uncertainties. Now, however, there is evidence of a change. Wellhead prices have increased, as consumer subsidies have been reduced, while returns for investors have improved.

While Repsol’s experience highlights Argentina’s political risk—the government said that the Spanish multinational was not investing enough—analysts say the country’s desire to bolster domestic energy reserves should ensure that state interference is minimized. The Argentinian government says it is hopeful of reaching a settlement with Repsol by the end of the year.

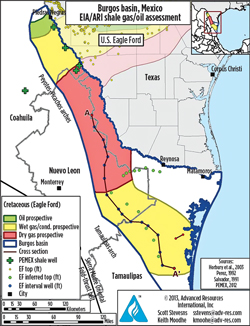

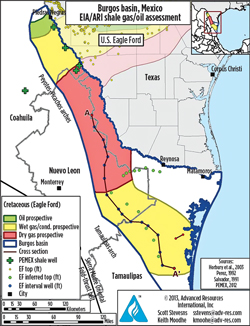

Mexico. The Mexican portion of the highly-productive Eagle Ford shale formation, which extends from Texas into Mexico’s Burgos basin, is an obvious focus for drillers, active in the U.S., who are seeking to expand out of a now-saturated market, Fig. 2.

|

| Fig. 2. Burgos basin outline, and shale gas and shale oil prospective areas (image courtesy of EIA, ARI). |

|

The Eagle Ford stretches across the western margin of the Burgos basin, where the formation interval ranges from 100 m to 300 m thick, with total organic content (TOC) averaging around 5%. The basin is estimated to hold around 345 Tcf of Mexico’s TRRs, which at 545 Tcf are the world’s sixth-largest. The Mexican section of the Eagle Ford also holds 6.3 Bbbl of the country’s estimated 13.1 Bbbl of technically recoverable shale oil reserves.

While Mexican President Enrique Pena Nieto has proposed reforms that could allow foreign investment in oil and gas, for the first time in decades, it is unclear if, or when, these will be implemented. It is also likely that the government and Pemex, the state oil firm, would seek to develop the more lucrative, conventional oil reserves.

Shale oil would be more expensive to exploit than conventional oil reserves. And shale gas developments would necessitate costly infrastructure to move the supply to domestic or foreign markets; it may even require the construction of LNG plants. Sending the gas to the already well-supplied U.S. market, where prices are low, would not be an economically attractive option.

Pemex has been conducting exploratory shale gas drilling since 2010, and so far, it has sunk just five wells. However, the company plans to drill around 175 wells by 2015.

Brazil. Latin America’s third-largest shale gas reserves—after Argentina and Mexico—lie in Brazil, which has TRRs of 245 Tcf. These reserves are in three basins—namely Paraná, Solimões and Amazonas—which have been assessed as potential shale plays. These basins already produce conventional oil and gas. Once assessed, other basins may be shown to be shale plays.

The Paraná basin, which covers some 747,000 sq mi, stretches across parts of Paraguay, Uruguay and Argentina, as well as Brazil. The Brazilian section is covered by flood basalts, which increase drilling costs and make seismic surveying difficult.

As is the case in Mexico, Brazil’s heavy investment in its conventional hydrocarbon reserves—notably its offshore pre-salt discoveries—means that more costly-to-extract, less-profitable shale gas is unlikely to receive much attention, in the near term. So far, no shale drilling has been undertaken.

EUROPE

Europe is home to substantial shale reserves (TRRs of 470 Tcf of shale gas in the European Union); however, commercial quantities of such gas have yet to be produced anywhere on the continent. While the shale geology is more complex than much of that in North America, the lack of success may be due more to the very limited extent of exploration and investment undertaken, so far. Poland has taken the lead in shale gas exploration; however, results there have been largely disappointing, to date. Now the UK and Ukraine are beefing up their efforts to create a shale industry, by offering more attractive terms to drillers.

Environmental concerns have sparked grassroots opposition in several European countries, sometimes leading to fracing bans. Such concerns have also spurred the European Commission (Editor’s note: the European Commission is the EU’s executive body, which seeks to represent the interests of Europe as a whole—as opposed to the interests of individual countries) to prepare legislation that could introduce tougher requirements for environmental impact assessments, for the EU shale sector. “Project managers will need to bear in mind the cost and time implications of this, if the legislation comes into force,” said Darren Spalding, a London-based attorney at law firm Bracewell & Giuliani.

Poland has Europe’s largest shale gas reserves, with estimated TRRs of 148 Tcf, across four basins, and TRRs of shale oil estimated at 3.3 Tcf. The country is a forerunner in shale gas exploration, outside of North America, and in recent years, it has attracted investment from major energy firms. Chevron, ConocoPhillips and Eni are among companies operating in the sector.

Despite strong governmental support, and limited public opposition, a string of drilling failures has contributed to an exodus of players, such as Exxon Mobil, Marathon and Talisman. Some 50 wells have been drilled, without locating commercial shale gas reserves. Difficult geology, and excessive red tape, have also been cited as problems in the country. Proposed legislation, which is designed to improve investment conditions for drillers, has been criticized by some operators, for not going far enough.

The government, which is keen to reduce Russian gas imports, and its heavy reliance on coal for power generation, hopes that recent successful drilling by Lane Energy (70%-owned by ConocoPhillips and 30% by London-listed 3Legs Resources) in mid-2013 will turn the tide. In August, the company said it was producing around 8 Mcmd of shale gas, from its LE-2H horizontal well, in the Baltic basin of northern Poland, Fig. 3. While still not at commercial levels, this is still one of the highest flows achieved in Europe, to date.

|

| Fig. 3. Łebień LE-2H operations (image courtesy of 3Legs Resources). |

|

The Baltic basin is considered to contain the most potential. The Podlasie basin, in the east, and the Lubin basin (which extends into Ukraine), to its south, are other targets for explorers. The Fore Sudetic Monocline, in the southwest, may also hold substantial reserves.

Ukraine has led the field in Europe, in terms of attracting fresh investment to the global shale sector this year, as the country strives to reduce its dependence on imports from Russia. Two major deals have paved the way for a rapid acceleration in exploration, but the extent of commercial potential remains uncertain.

The country has estimated TRRs of 128 Tcf of shale gas and 1.1 Bbbl of shale oil, according to the EIA. The two main shale plays are Olesska field, in the west, a continuation of Poland’s Lublin basin, and Yuzivska field, in the east, which is in the Dniepr-Donets basin. The latter is a mid-to-late Devonian structure containing a thick sequence of Lower Carboniferous black shale.

So far, little drilling has been done, but this is now set to change. In June, the government signed a 50-year production-sharing agreement (PSA) with Shell, which could be worth $10–$50 billion, depending on exploration results, to explore and develop shale gas resources in Yuzivska field. The deal permits 70% investor recovery and a 16.5% governmental revenue take. Earlier this year, the government said that the field could be producing 7–20 Bcm of gas, annually, by 2018. In October, Shell said that it planned to drill its first 15 wells during 2014.

A PSA, worth up to $10 billion, with Chevron to develop shale gas in Olesska field is also set to be signed, once the draft has made its way through Ukraine’s political process. Under the deal, Chevron would invest $350 million to assess reserves on 5,260 sq km of the field. The company also has interests in the Polish section of this formation.

UK shale gas exploration has been limited, to date. However, a promise of governmental support, and attractive incentives, could turn the UK into one of the EU’s major players, if commercial quantities of gas can be found. The presence of a conventional oil and gas industry, in the country, should aid investor confidence. However, public opposition to shale drilling, on environmental grounds, is evident, and has resulted in disruption to some work; most recently, a well being drilled as part of shale oil exploration in southern England by Cuadrilla Resources, Fig. 4.

|

| Fig. 4. Aerial photograph of a Cuadrilla Resources rig site in England. |

|

TRRs of shale gas are estimated at 26 Tcf and those of shale oil are 700 MMbbl. The EIA’s estimate of shale gas-in-place is much higher, at 632 Tcf. In June, the British Geological Survey doubled its estimate of gas-in-place in a swathe of northern England (including the Bowland shale and surrounding areas) to a range centered on 1,300 Tcf.

Shale gas drilling has, so far, been focused on the Bowland shale of northwestern England; however, other Carboniferous formations across northern England and central Scotland, and Jurassic shales in southern England, are also regarded as prospective. The geology of much of these formations is more complex than those in the U.S., meaning that drilling costs are likely to be much higher.

One sign of growing interest in exploration is the arrival of investment from larger firms. The sector has, until this year, been occupied by pioneering innovators. In June, Centrica bought a 25% stake in licenses in the Bowland shale, operated by Cuadrilla Resources. In October, France’s GDF Suez took a 25% stake in 13 Bowland shale licenses held by Dart Energy. GDF is paying Dart $12 million in cash, and funding $27 million in exploration and appraisal costs. If these operations yield results, and the government delivers on its promised incentives, other major players may also enter the UK market, Fig. 5.

|

| Fig. 5. View of a rig site in the UK (image courtesy of Cuadrilla Resources). |

|

Other European countries. Several prospective shale plays exist elsewhere in Europe, but development has been stymied, in several countries, by bans on hydraulic fracturing, introduced by governments in response to public opposition.

France is thought to have the continent’s second-largest shale gas reserves after Poland (TRRs of 137 Tcf); however, a fracing ban has been in place since 2011, when exploration licenses, held by Total and others, were cancelled. In October, the constitutional court upheld the ban in response to a challenge by Dallas-based Schuepbach Energy, one of the licensees affected.

Other countries with bans in place—at least while environmental reviews are carried out—include Germany, the Netherlands and Bulgaria. The government in Romania, where Chevron is a license-holder, is keen to push on with shale gas exploration, but is, nevertheless, meeting stiff opposition from the general public. Romania’s TRRs are estimated at 51 Tcf.

Russia. While Russia has the world’s largest estimated shale oil reserves (TRRs of 75 Bbbl) and ninth-largest shale gas reserves (TRRs of 285 Tcf), the country is in no hurry to exploit them. Instead, Russia is likely to prioritize its lucrative conventional reserves for the time being.

However, some resources are being directed to shale drilling. Exxon Mobil has agreed to collaborate with Rosneft in shale oil and gas exploration, and technology development. In 2012, the companies said they would drill pilot wells, in a tight oil formation, in the Bazhenov formation, in western Siberia, which has similar geology to the U.S. Bakken shale. Statoil has also signed an agreement with Rosneft to launch a pilot shale oil program in the Samara region, in the southeastern part of European Russia. The deal covers 12 blocks in the Domanik formation. Rosneft holds a 51% stake in the project, while Statoil holds the other 49% and will inject $60 million of investment. The Norwegian firm said, in August, that it also hoped to sign a deal, soon, to explore in western Siberia, and that it could start drilling there in 2014.

ASIA-PACIFIC

Most of the region’s known shale resources lie in China and Australia, the countries on which most investor attention has been focused. China has the lion’s share, but may lose out to Australia, in the short term, in attracting experienced shale drillers, who are looking to expand out of North America. Australia’s fast-growing conventional hydrocarbons sector has already proved a magnet for major foreign players, whereas China’s regulatory environment—while under reform—still remains complex and favors domestic companies over their foreign counterparts. Indonesia, India, Pakistan, Mongolia and other countries in the region are all keen to attract investment for shale development, but have made only limited progress so far.

China holds the world’s largest shale gas reserves (estimated TRRs of 1,115 Tcf) and third-largest shale oil reserves (TRRs of 32 Bbbl). To date, most exploration efforts have been focused on the Sichuan basin, in the southwest, and the more remote Tarim basin, in the northwest. A lack of expertise and equipment, and the challenges of complex geology, have limited drilling. With less than 200 wells drilled so far, China’s hopes of producing 2.8 Tcf of shale gas annually by 2020 look unlikely to be realized (see China Regional Report, p. 88).

The government has held two shale-licensing rounds, with results announced in 2011 and 2013. All blocks are held by domestic firms, ranging from the big state-run firms, such as China Petroleum & Chemical Corp. (Sinopec), to smaller players, including coal and power firms. While homegrown know-how is limited, it is growing, due, in part, to the involvement of Chinese firms in the North American shale market.

Foreign expertise has been called upon. In 2012, ConocoPhillips and PetroChina agreed to jointly explore 500,000 acres in the Sichuan basin. However, Shell is the biggest foreign investor in Chinese shale, investing up to $1 billion per year in exploration. In March, Shell signed a PSC with Sinopec to explore around 4,000 sq km of the Fushin shale gas blocks, in the Sichuan basin, where foreign firms are already active in the conventional oil and gas sector. Shell is also exploring with Sinopec in central China, where little drilling has been carried out, so far.

The extent to which foreign firms become further involved may depend on the extent to which regulations, governing foreign participation and sales into the Chinese market, are reformed.

Other Asian countries. Indonesia is actively seeking foreign investment in its shale sector. The country is seeking to exploit TRRs estimated, by the EIA, at 46 Tcf of shale gas and 7.9 Bbbl of shale oil. The government suggests that there could be around 575 Tcf of gas in the main shale formations of Sumatra, Kalimantan, Papua and Java. In May 2013, state firm Pertamina was awarded the country’s first shale gas license, for the Sumbagut block in North Sumatra, and said it would spend almost $8 billion on the project, as part of Indonesia’s efforts to make up for flagging, conventional oil and gas production. However, a complicated regulatory environment, limited financial incentives and poor infrastructure could deter foreign investment in shale resources, as they have done in the nation’s conventional sector.

Both India and Pakistan also hold potential for shale gas and oil, which their respective governments would like to exploit. However, their ability to exploit the reserves is limited by their infrastructure and funding. Many of India’s reserves—mainly in the Cambay, Krishna-Godavari, Cauvery and Damodar Valley basins—are far from the pipeline network and feature difficult geology. A new shale gas policy, which was approved by the government in September 2013, is designed to speed up exploration. It also promises the licensing of new blocks in the near future.

In Pakistan, the largest reserves lie in the southern Indus and Baluchistan basins. India’s TRRs are estimated at 96 Tcf of shale gas and 3.8 Bbbl of shale oil, according to the EIA. Comparatively, Pakistan’s TRRs are 105 Tcf of shale gas and 9.1 Bbbl of shale oil.

Australia could be the next major shale gas and oil province to undergo development. The country has substantial reserves of both shale gas and oil; a large, existing conventional oil and gas sector; and a fast-developing LNG export sector to provide ready buyers. It is already basing some of those exports on unconventional resources, in the form of coal seam gas. However, rising costs in the oil and gas sector, in general, coupled with the need to direct much funding toward major conventional projects, could create a drag on shale developments.

Australia has TRRs of shale gas estimated at 437 Tcf, and of shale oil estimated at 17.5 Bbbl. The country’s main focus of shale exploration, which is still in its infancy, is the Cooper basin. This basin is also Australia’s main source of onshore gas. Estimated, risked recoverable shale gas reserves in the basin total 85 Tcf. Other prospective shale basins in Australia include the Georgina, Galilee, Bowen, Sydney, Canning, onshore Perth, Beetaloo and McArthur basins.

Significant investments are already being made in the nation’s shale sector. In February, Chevron agreed to pay up to $349 million to farm into two shale prospects being developed by Beach Energy in the Cooper basin. Santos has already embarked on a drilling program in shale and tight gas formations in the same basin. ConocoPhillips, Total, Mitsubishi Corp., Statoil and India’s Bharat Petroleum are among firms that have also made investments in prospective shale projects.

In November 2013, Armour Energy said that it had carried out what it described as the first successful use of multi-stage, hydraulically stimulated, horizontal drilling, in the Australian shale gas industry, at its Egilabria-2 well in the Lawn shale of northern Queensland. Initial gas flows to surface, and a flare of at least 2 ft, were observed. The company provided no flowrate data.

AFRICA

Northern Africa. Algeria has the world’s third-largest shale gas reserves (TRRs estimated at 707 Tcf), while Libya has the world’s fifth-largest shale oil reserves (26 Bbbl), as well as an estimated 122 Tcf of shale gas. Morocco and Tunisia also have plans to develop their shale gas reserves, but they have yet to make any significant strides.

Algeria’s shale gas is located across the Mouydir, Ahnet, Berkine-Ghadames, Timimoun, Reggane and Tindouf basins. While Shell, Exxon Mobil and Eni have all held talks with the government over the development of these resources, no serious drilling has occurred, so far. Sonatrach, the state energy company, has said that it plans to drill pilot wells, in the most promising shale formations, at less than a 3,000-m depth.

Libya’s efforts to develop its shale reserves have been hampered by continued unrest, since the overthrow of Muammar Gadhafi in 2011, which also has brought conventional hydrocarbon production to periodic halts. The Ministry of Oil and Gas has said it may assess its shale gas strategy in mid-2014, to see if progress would be possible.

South Africa is the country with the world’s eighth-largest shale gas reserves (TRRs of 390 Tcf). These reserves are located mainly in the Karoo basin, which covers much of the center and southeast of the country. Lacking in conventional gas, and over-reliant on coal for power, the government is keen to exploit its shale reserves—if environmental, and practical, obstacles can be overcome. Plans to develop shale resources have met with environmental protests over potential damage to the Karoo, a semi-arid wilderness area (with little water to spare for hydraulic fracturing) that has a growing tourist industry.

In September 2012, the government lifted a moratorium that had been in place, since 2011, on shale gas exploration. In October 2013, it took another step toward permitting exploration, by proposing new regulations to govern shale gas drilling. However, the need to ensure careful water management, and satisfy environmental concerns, could delay drilling for a while longer.

Royal Dutch Shell, Falcon Oil & Gas, Anglo American, and a group including Sasol, Statoil and Chesapeake applied for permits prior to the moratorium and could be well-placed to lead drilling efforts, if they arise. Shell, the largest acreage-holder, said in 2012 that it could invest at least $200 million in shale gas exploration.

MIDDLE EAST

While most Middle Eastern countries are focused mainly on developing conventional oil and gas resources, some have reason to invest in shale oil and gas, too. Jordan, which has few conventional hydrocarbons, is eager to develop its unconventional resources, to reduce costly imports. Saudi Arabia would also like to develop shale gas, to reduce its use of oil in the power sector. Oman, which is already producing from tight gas reserves, has also expressed interest in shale gas exploration.

In October, Saudi Arabia said that it plans to be among the first countries, outside North America, to use shale gas for power generation. The government says that it believes the Kingdom’s shale gas reserves could total 600 Tcf, more than double its proven conventional gas reserves. However, while the country has drilled a few test wells, water scarcity and subsidized domestic gas prices are likely to prevent the sector from taking off for several years.

The most promising formation in Jordan is the Batra shale in the Hamad and Wadi Sirhan basins, of eastern Jordan, and in sections of the Southern Desert region. These potential reserves also extend into Saudi Arabia and Iraq.

|