|

IAN LEWIS, Contributing Editor

fSouth Africa is opening up as a new frontier for energy firms seeking fresh acreage in a region that has yielded substantial hydrocarbon finds in recent years. Promising geology, low political risk and a relatively benign investment climate add to the attractions, but it remains unseen whether this largely unexplored country can yield major finds matching those made elsewhere in southern Africa.

|

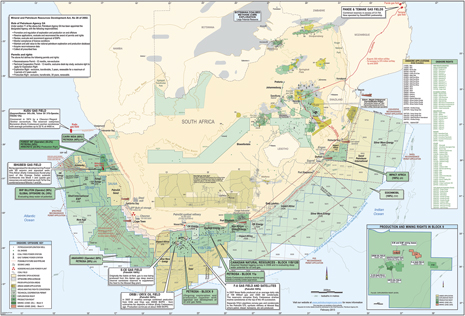

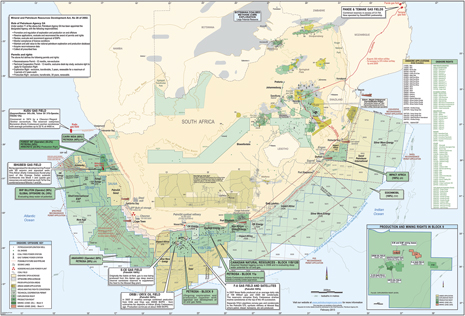

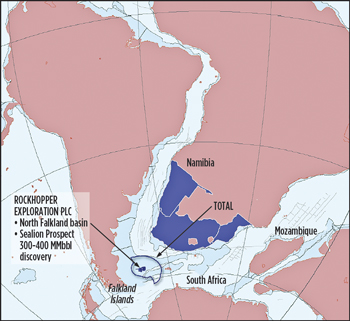

| Fig. 1. As this map shows, numerous IOCs have acquired acreage offshore South Africa recently. Map courtesy of Petroleum Agency SA. |

|

Growing interest in the country was underlined by ExxonMobil’s entry to the offshore sector in December, when the supermajor announced that it agreed to take a swath of acreage near Durban on the east coast. The move follows recent acquisitions of offshore exploration acreage by other international oil companies (IOCs), including Royal Dutch Shell, Anadarko, BHP Billiton and Cairn India. France’s Total also holds acreage off the southern tip of the country, Fig. 1.

Exxon agreed to take a 75% stake in the Tugela South Exploration Right, covering 2.8 million acres, which is held by Impact Oil & Gas Limited, a small UK-based explorer. The supermajor also took a 75% stake in future exploration rights held by Impact in three other offshore areas under technical cooperation permits (TCPs), which remain subject to governmental approval. A TCP is an exclusive right to study an area for one year.

Separately, the company was also granted a TCP by the government, to study the hydrocarbon potential of the Deepwater Durban basin, which covers some 12.4 million acres. The prospectivity of Exxon’s acreage extends to an almost 3,000 m in the deepest part of the area.

In February 2012, Shell won exploration rights for some 37,000 sq km of the Orange basin deepwater area off northwestern South Africa, and has since been carrying out seismic surveys. In August, Anadarko acquired exploration rights for blocks southwest of Cape Town, and Cairn India farmed into a block in the Orange basin. BHP Billiton acquired majority interests in two blocks northwest of Cape Town in 2010, and has said it is keen to carry out an exploration program.

Companies also plan to exploit South Africa’s potentially huge shale gas reserves, if they meet environmental regulations and are granted exploration permits (see sidebar article, “Future of shale gas uncertain”).

This surge in interest in South Africa comes against a backdrop, where eastern and southern African countries, such as Mozambique, Tanzania and Uganda, have been yielding sizeable hydrocarbon finds over recent years. However, the reasons for it are more complex than that.

“It would be incorrect to say that international investors are coming to South Africa because of the finds in Mozambique or the Rift Valley. What is true is that those successes have led industry to re-visit areas that were passed over 20, 30 or 40 years ago, when we had a very different market,” said Will Barker, managing director of Sunbird Energy. Sunbird is an Australian-registered, South Africa-focused explorer, which owns a majority stake in Ibhubesi, one of the country’s few viable gas fields, set in the Orange basin.

Offshore exploration of South Africa has had a checkered history. Foreign firms were deterred from exploring in the 1970s and 1980s, due to international political sanctions on the country, leaving state-owned firms to carry out limited exploration. The creation of Petroleum Agency SA, the oil and gas sector regulator, in 1999, and PetroSA, the state energy firm, in 2001, provided a more streamlined investment framework for post-Apartheid South Africa.

FAVORABLE ENVIRONMENT

Barker says the country’s fiscal regime for energy investment is favorable, recognizing its status as an immature oil and gas province. It is also carries low political risk, in a region where risk perceptions are improving all the time as IOCs become more experienced in operating there.

“There is pressure on oil companies to secure more resources in politically stable areas, away from such places as the Middle East. That interest is not isolated to South Africa, but it can also be seen in places like Kenya and previously ignored areas like the Arctic,” said Marné Beukes, an Africa analyst at IHS Energy.

South Africa should be able to capitalize on such assets as its developed infrastructure, access to advanced technology; and skilled workers. To become a regional hub for oil and gas as the largest economy in the region, it should also provide a ready market for of oil and gas, especially if efforts, to make the domestic gas market more attractive to producers, come to fruition.

However, regional factors are adding momentum to the sector. Most of the IOCs with South African blocks are also drilling in the rest of eastern and southern Africa, which means they have both technology and skilled manpower not close by, and are gaining confidence while working in new African territory.

SOUTH AMERICAN CONNECTION

At this early stage, there is little hard evidence of significant oil and gas reserves off most of South Africa. So far, the limited exploration that has taken place has largely been at relatively shallow depths and mainly yielded small amounts of gas. South Africa has proven oil reserves of only around 15 million bbl.

|

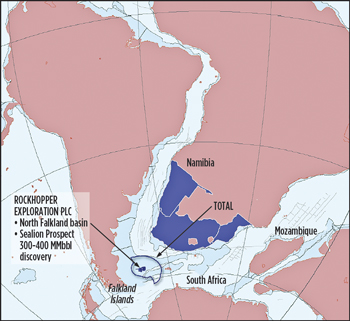

| Fig. 2. Geological similarities between the once-adjacent offshore areas of Western Africa and South America raise hopes that South Africa could yield finds similar to those across the Atlantic. Map courtesy South Africa Oil and Gas Alliance. |

|

Explorers have, instead, played up the relationship between southern Africa and the areas of South America, including Brazil and the Falkland Islands, where large oil and gas reserves are already being exploited or believed to lie, Fig. 2.

While South America’s oil fields may be over 3,000 mi (5,000 km) away today, they are near neighbors of South Africa, Namibia and Angola geologically. The two continents are believed to have been joined, before plate movements pulled them apart. As the continents split, the organic matter that would later become hydrocarbons was laid down in a shallow sea that formed between them. If there is oil and gas on one side, then there may more on the other side—that is the argument.

Angola has produced substantial oil and gas reserves, but there is no guarantee that multi-billion-barrel oil reserves such as Brazil’s Santos and Campos basins, or the recently discovered Sea Lion prospect off the Falklands (which could hold up to 400 million bbl) exist in southern Africa.

GAS PROSPECTS

More solid evidence of prospectivity comes from finds made closer to home, notably in the Orange basin, a sedimentary feature that straddles the maritime border between South Africa and Namibia. Shell and others with exploration rights in the South African Orange basin Deepwater License Area, hope that modest finds, such as the Ibhubesi gas field in South African waters and Namibia’s Kudo gasfield, are indicative of greater reserves elsewhere.

“Gas and oil, albeit in very small quantities, as found offshore South Africa and in the Kudu gas find off Namibia, boosts interest, as it is clear there is a working hydrocarbon system,” said Beukes.

The Kudu gas field was discovered in the early 1970s by Chevron, but it has yet to be commercialized. This is due to the failure to develop a power project in Namibia that would take the gas. Kudu has relatively small-scale proven reserves, estimated at 1.3 Tcf, although possible reserves could be as high as 9 Tcf. UK firm Tullow Oil, Kudu’s operator since 2004, has struggled to make headway. The company remains in talks with state firm NamPower over project development and a possible gas sales agreement.

Several blocks around the Kudu concession are licensed to Brazil’s HRT Participações em Petróleo, which recently sold a minority interest in them to Portugal’s Galp Energia. HRT is about to begin exploratory drilling in Namibia using the Transocean Marinas semisubmersible rig, which has been shipped to the country from Ghana. The campaign is scheduled to kick off in March in the Walvis basin, further north, before moving to the Orange basin.

SEISMIC UNDERWAY

Shell acreage on the South African side of the border is located between 150 km and 350 km offshore, in water depths ranging from around 500 meters to 3,500 meters. However, the company is unlikely to drill just yet.

“It is too early to comment on the exploration program in detail, beyond our intention to acquire and analyze the seismic data,” said Jan Willem Eggink, upstream manager at Shell South Africa. “Our intention is to acquire and analyze the seismic data within the first three years. Further exploration activities will be determined by results from these activities.”

A seismic survey of an 8,000-sq-km section of Shell’s license area, carried out by Dolphin Geophysical on the Polar Duchess vessel, was completed in February.

ExxonMobil’s acreage lies down the east coast of Africa from Tanzania, where the company, in partnership with operator Statoil, last year discovered up to 9 Tcf of gas offshore. It is even closer to bigger offshore discoveries made by firms, including Anadarko and Italy’s Eni in Mozambique. In February, the Italian firm announced a new 4-Tcf gas discovery in the country, bringing the company’s estimate of reserves to 75 Tcf of gas in place.

Anadarko and Eni are expected to make an investment decision on the construction of a two-train LNG plant in Mozambique later this year. ExxonMobil has yet to outline its exploration plans.

DOMESTIC DEMAND

Explorers in South Africa may not need to resort immediately to expensive LNG projects, when they do find gas, if plans to enhance the role of gas in South African power provision are followed through. The government is seeking to diversify supply away from coal—on which it is dependent for over 85% of its power output of around 40 gigawatts (GW)—and meet spiraling energy demand.

The energy ministry’s Integrated Resource Plan, released in 2011, calls for a minimum 711 MW of new combined-cycle gas turbine (CCGT) capacity to be developed in 2019-21, and a further 1.7 GW in 2028-30. Further gas demand will come from Sasol’s gas-to-liquids (GTL) plant at Mossel Bay and industries, like petrochemicals and fertilizer production.

Boosting gas sales domestically will also require an overhaul of pricing, which has thus far proved unattractive to project developers. However, some investors are more optimistic about getting long-stalled projects off the ground. Sunbird Energy’s purchase of a 76% stake in the Ibhubesi field, from operators that had held the asset since 1998 without being able to develop it, could pave the way for that project to push ahead. The stake was purchased for $1.5 million from Forest Oil Corp and Anschutz Corp. PetroSA continues to hold the other 24%.

If it does go ahead, the Ibhubesi development would be the first production infrastructure in the Orange basin and signal to other investors that the South African offshore sector is open for business. “We believe the market conditions are now right for the development of this strategic gas resource,” says Sunbird’s Barker. “South Africa is an energy-hungry market, and the government has recognized the need for gas as a vital part of the energy mix.” Barker suggests that the success of South Africa’s energy ministry in mobilizing more than $5 billion of finance for clean energy projects last year, with more planned to be given the go-ahead later this year, indicates a wider appetite for South African energy projects from international investors.

Ibhubesi has a discovered 2C resource of 870 Bcf, with the potential for considerably more across parts of its production license area that have yet to be fully explored, according to Barker. Reservoir depths in the field range from 3,000 to 3,500 m at average water depths up to 250 meters.

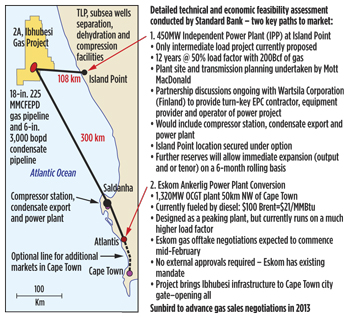

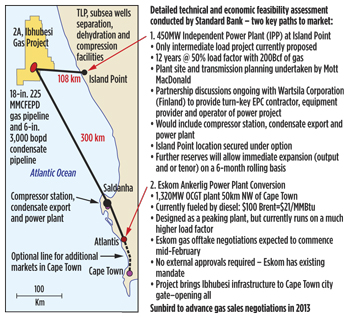

However, Sunbird, while it is in talks with state power utility Eskom, has yet to negotiate a gas sales agreement, and progress is still dependent on the development of necessary infrastructure. That would either take the form of a new 450-MW independent power project on the coast adjacent to the field, served by a 108-km pipeline, or a 300-km pipeline taking gas to Eskom’s existing 1.32-GW Ankerling plant 50 km north of Cape Town. Ankerling intends to provide peaking power, using gas, but has been running mainly on expensive diesel at much higher capacity than originally envisaged, Fig. 3.

|

| Fig. 3. As South Africa’s government looks to coal alternatives, it is in talks with companies like Sunbird, which is hoping to supply gas to domestic consumers. Map courtesy of Sunbird Energy. |

|

Gas from Ibhubesi was originally slated for use at Sasol’s Mossel Bay GTL plant, east of Cape Town, which is running low on supply from a small gas field close to the plant. It remains unclear from where future gas for that project will be sourced.

Beukes says the industry would like more clarification over the way that gas and pipeline transit fees are to be determined and that it is pushing for Eskom to give IPPs improved access to the national grid. “These obstacles need to be cleared first before one can conclude that there are positive changes in gas power development,” she said.

|