OPEC’s upstream investments: Cooperation between producers and consumers is key

JUDE CLEMENTE, JTC Energy Research Associates “All of us, consuming, producing and transiting countries, alike, are becoming more and more dependent on each other. Security of supply is important for us, but other countries seek security of demand. This is the age of energy interdependence,” –Jose Manuel Durao Barroso, In the International Energy Outlook 2011, the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s (EIA) National Energy Modeling System forecasts that domestic oil (liquid fuels) consumption will increase 5% to 20% in the next 20 years.2 With just 2% of the world’s proven endowment, and despite recent strides in domestic production, half of the 19.5 million bpd of liquids that the U.S. uses is imported from other countries. Canada’s massive oil sands resource in Alberta holds some 180 billion bbl of “free market” oil, but policy, such as the delay of the Keystone XL oil pipeline expansion project, could limit its availability to the U.S. market. Mexico, the next most important U.S. supplier, passed peak production in 2005, and its own growing economy will require greater amounts of fuel. Meanwhile, as demonstrated by the “NOPEC bill,” the national security mission to break the U.S. free from the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) has been a steady drumbeat:

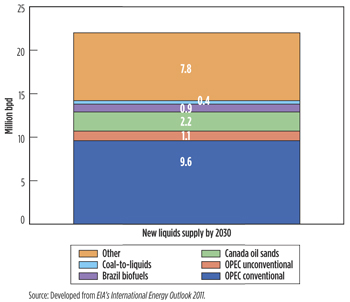

OPEC, however, has produced around 40% of the world’s oil since 1980 and met a quarter of total U.S. needs since the early 1970s. On the supply side, perhaps the most important faculty that OPEC can bring to bear is a surplus production capacity, which can quickly come online when a shortage in the market puts pressure on the price structure. Expected to rebound to 3.5 million bopd this year, low OPEC spare-capacity levels increase the demand for expensive inventories. Saudi Arabian policy is expected to maintain a spare capacity cushion that tracks a percentage of global demand, not a constant fixed number. Looking forward, quantity and quality ensure that OPEC’s oil will assume an even larger role in the global market. BP reports that member countries hold 77% of the world’s proven reserves and have the lowest average production costs.6 The total “finding and lifting” costs of Saudi crude, for instance, are often just $5/bbl; in the U.S. offshore, costs can average around $60/bbl. Historically, the benchmark crude types in the U.S. (West Texas Intermediate and Brent) sell at a $4 to $6 premium to OPEC’s basket and have insignificant production rates (i.e., less than 500,000 bpd). Saudi Arabia’s abundant Arab Light and Extra Light are of similar quality to the U.S. benchmark crudes, and Algeria’s Saharan Blend is among the highest quality crude oils in the world, averaging 45°API. In fact, European countries have relied upon Algerian oil to satisfy increasingly stringent regulations for the sulfur content of gasoline and diesel fuel. In 2010, Nobuo Tanaka, then-executive director of the International Energy Agency (IEA), confirmed the geological reality: “The dependency on the Middle East countries, especially OPEC countries, will increase from the medium-to-long term. It’s inevitable.”7 OPEC reports that member countries have produced only 20% of their 60% share of the world’s original oil endowment, compared to over a 50% extraction rate for non-OPEC countries.8 The EIA is more optimistic about outside production, but it still expects pricier unconventional oils to constitute the bulk of new non-OPEC supply until 2030. As indicated, policy (e.g., low-carbon fuel standards and tariffs) could restrict us from these resources, due to their higher life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions and a preference for protecting domestic industry. Thus, deprived of OPEC, the U.S. could effectively be blocked off from 65% of the projected incremental oil supply in the next 20 years, Fig. 1. In addition, the 2010 Deepwater Horizon accident hurled our offshore energy industry into regulatory limbo, and tighter, more expensive regulations are proceeding.

To meet global oil demand by 2030, the IEA’s required investment estimates have been consistently elevating. For example, in 2004, the IEA concluded that the world oil system needed $3 trillion by 2030; in 2007, it was $5.4 trillion; and in 2010, the number was $6.5 trillion.9 The IEA’s World Energy Outlook 2011 now reports that $10 trillion is needed to meet projected demand from 2010 to 2035, with the upstream sector accounting for 85%.10 Simply put, oil’s dominance in the U.S. energy mix is virtually guaranteed to continue. Even under the IEA’s best case policy projection for renewables, 450 Scenario, which unrealistically assumes that fossil fuel use will peak before 2020, oil constitutes a leading 27% of U.S. energy demand in 2030, as opposed to 37% today. We should therefore encourage more oil investment in all countries, since oil is sold on a global market, and competition for all fuels will be increasingly fierce. In this light, the present analysis examines the challenges and opportunities for OPEC’s upstream capacity investments. UPSTREAM CHALLENGES Despite overwhelming reserves, OPEC’s share of world oil production has been fairly constant at 40%. Many factors explain the lack of upstream investment in the past few decades, and why member countries remain hesitant to implement large-capacity expansion programs. The high spare capacity and oil price decline of the 1980s, and most of the 1990s, threw the industry into a recession and reduced the incentive to invest. Over time, geopolitical instability and war have prevented capacity expansion in many OPEC nations, and economic sanctions against certain member countries have limited the access to technology and foreign capital. The investment complications for OPEC and its powerful national oil companies (NOCs) have traditionally included:

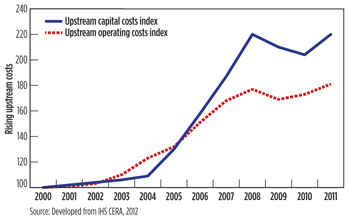

OPEC’s recent investment opportunities have been complicated even more by a global recession, historically volatile prices and mounting instability in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. Indeed, the distinction between transitory and permanent price movements continues to blur. The future uncertainties facing OPEC in the current context are even more complex. Emerging challenges go well beyond transient issues and revolve around the potential long-term impact of climate change policy on oil demand, especially among the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and its majority share of global consumption. The willingness of OPEC to invest in upstream capacity is under attack on three main fronts: 1. Policy’s impact on demand. For exporters, energy security is based on the predictability of demand, as more variables in demand pose investment risks along the entire supply chain. OPEC’s annual World Oil Outlook has been significantly influenced by two recent Western policy initiatives—the U.S. Energy Independence and Security Act (EISA) and the European Union (EU) climate and energy legislative package. EISA’s increased Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards, alone, decreased OPEC’s 2010 projection for the call on its oil in 2030 by around 2.3 million bpd—an entire Venezuela’s worth of production.11 With many low-carbon policies still squarely on OECD’s agenda, the risks for OPEC are heightening. Mohamed Hamel, OPEC’s Senior Advisor, has said that OECD policy initiatives that “discriminate against oil” mean that OPEC’s upstream investment requirements until 2020 “could lie within a huge range of $230 billion and $500 billion.”12 This uncertainty gap ripples across the entire supply chain, triggering concerns over unneeded capacity and wasted precious resources. The call on OPEC’s oil in 2020 is expected to lie between 29 million and 39 million bpd, compared to 35.2 million bpd in 2011. In addition, other policies, such as EISA’s mandate to produce at least 36 billion gallons of renewable and alternative fuels by 2022, can discourage OPEC’s upstream investments. Compared to the reference projection for 2030, the IEA’s latest low-carbon paths, New Policies and 450 Scenario, further lowered the OECD’s use of oil by 5% and 20% respectively. OPEC wants compensation, if UN climate deals cut oil sales. 2. Higher costs. While technological advancements in finding and extracting oil have led to greater yields from more remote reservoirs, rising exploration, development and production costs have hindered upstream projects. Areas of high activity, such as OPEC’s MENA region, have seen higher-than-average cost increases, compared to North America and Europe, where activity has been typically slower. The IHS CERA upstream capital and operating cost indices have been steadily increasing, Fig. 2. This trend is unlikely to be reversed: 1) higher demand could create shortages in labor, equipment and raw materials; 2) the Deepwater Horizon accident remains a disruptive factor; and 3) overall structural changes, most notably the transition toward deeper water and frontier regions, all suggest that the upward movement in cost is permanent.

3. High-quality and timely information issues. Reliable information and data are central to well-functioning energy markets. On the international level, the IEA has led the charge in improving the flow of information surrounding the world energy system. The International Energy Forum seeks “energy security through dialogue” and comprises over 90% of global oil and gas supply and demand.13 Recent years, however, have highlighted the need to extend the concept of energy security to the global level by more fully engaging China, India, Indonesia, Brazil and other large emerging non-OECD nations. The IEA reports that the non-OECD now consumes 57% of the world’s primary energy, compared to 46% in 2000, and will constitute all new oil demand through 2030. The rising non-OECD powers must be brought into coordination with the existing IEA energy security system to identify common interests and objectives. It is especially vital to incorporate China and India—together holding nearly 40% of humanity—into the global network of energy trade and investment. Staggering economic growth has quickly uprooted these nations from self-sufficiency to a growing reliance on international energy markets. The oil import dependency of China (30% to 60%) and India (60% to 70%) has been deepening over the past decade. Booming “ChIndia” will account for over half of the 20 million bpd of new global growth in oil demand by 2030. High-quality and timely information is the global counter to the supply shortfalls that this mass arrival could ignite. UPSTREAM OPPORTUNITIES Despite the unsustainably soft prices that can result from over-investing, OPEC recognizes that the “increased use of fossil fuels is consistent with protection of the environment, through the development and dissemination of advanced cleaner fossil fuel technologies.” OPEC concludes that OECD oil demand has peaked, and member countries are now banking on the opportunities that are emerging from the expanding non-OECD economies. Over the next 30 years, Exxon Mobil projects that the world’s fleet of personal vehicles will double to 1.6 billion, the “vast majority” of which will be petroleum-only outside the OECD.14 Looking forward, although the recent political turmoil in MENA could be sustained and further disrupt investment spending, OPEC seeks an even more critical role for itself. After all, the upstream oil industry is the single most important sector in the fast-growing OPEC economies, where, now, more wary governments must bolster the rising expectations of young populations. Notwithstanding the challenges outlined above, large investments to expand upstream capacity are underway in member countries. Upstream projects reflect the policies laid out in OPEC’s Statute and Long-Term Strategy. More specifically, they support “security of supply to consumers by expanding production capacity” and offer “an adequate level of space capacity.”15 According to the Secretariat’s latest upstream database, at least 135 projects are expected onstream between 2009 and 2017, adding a hefty 13.3 million bpd of capacity, Table 1.16 OPEC’s investment outlook, however, is now quite muddled. There is no official word yet, but the claim made in 2010—that rebounding prices had all 35 upstream projects that were delayed or considered for cancellation back on track—may no longer hold true.17

The unrest sweeping across MENA has raised prices, and the Iran-West nuclear standoff could cause the once improving Saudi-Iranian oil policy relationship to relapse. In February, Iran halted supplies to France and the UK, after the EU decided to boycott Iran’s oil, starting July 1. The EU debt crisis has cut OPEC’s estimate of global demand growth for 2012 by 11%, but a more stable U.S. economy, and the shutdown of nuclear plants in Japan, should boost demand.18 On the bright side, production schedules and output in war-torn Iraq and Libya have exceeded expectations. Politics, not geology, has made price-hawk Iran the only OPEC nation facing a net reduction in production capacity by 2020. OPEC says that its upstream investment requirements until 2015 lie in the wide range of $100 billion to $220 billion. By 2020, global oil demand is projected to increase 13%, and OPEC figures that its E&P requirements by that time range from $180 billion to $410 billion. Over the long-term, where investment factors are most variable, OPEC expects global oil demand to increase almost 25% by 2030. OPEC puts the world oil industry’s cumulative upstream investment needs over the next 20 years at $2.3 trillion, but estimates that only $620 billion of this amount is required by the organization, itself. From 2009 to 2030, OPEC anticipates that its share of global supply will extend from 39% to 45%. In other words, OPEC anticipates a 6% market share gain by 2030 while investing less than 30% of what non-OPEC nations will need to spend. OPEC realizes that growing global demand will inevitably collide with its dominance of reserves, because “long-term supply paths are linked to the resource base.” OPEC has called on consumers to adopt transparent and predictable economic, energy and environmental policies to promote free access to markets and financial resources. Member countries have generally indicated that they want “reasonable” oil prices, now in the $85/bbl range, to help establish the market stability required for the expansion of upstream and downstream capacity. Price volatility leads to uncertainty over future demand, lowers investor confidence and stymies global economic development. In contrast, greater transparency and predictability would serve common interests and help balance international markets. OPEC is concerned that futures prices are based on a narrowing volume of physical trading in major benchmark crudes. Non-OPEC nations should also bear in mind that member countries view runaway oil prices as unsustainable, since they erode global economic growth, consumption and revenue inflows. OPEC is typically not served by price maximizing behaviors, because they routinely lead to public uproar and refocus the spotlight on alternatives. Thus, to OPEC, high oil prices are ultimately a threat to the very hallmark of its existence—the ongoing demand for more oil. CONCLUSION On basically every level, we live in an increasingly interdependent world, where dialogue and cooperation are the best path forward. Oil will remain the centerpiece of the world energy economy, and OPEC is clearly the supreme resource. Although not blameless in recent oil price surges (social spending programs are increasing break-even prices), OPEC’s general position is that energy security is a two-way street, where security of supply is matched by security of demand. For the world oil system to attain the $10-trillion investment level required by 2035, the U.S. should lead by promoting flexibility and market adjustments, engaging those countries who are decisive for the global response to a supply disruption. Additional joint ventures and technological transfer are needed on the basis of fair commercial terms, consistency and reliability. The IOCs and OPEC countries should build new relationships by identifying common ground for a mutually acceptable fiscal and legal framework. There are huge volumes of conventional and unconventional oils still to be developed, with no “peak oil” in sight. The key constraint is the surface infrastructure to produce, process and deliver the oil. The U.S. has not imported less than 6 million bpd since 1985, and in the 39 years after President Richard Nixon launched “Project Independence,” our import dependency has doubled to 60%. The push for more wind and solar power will not alleviate our fundamental need for more oil, because oil generates less than 2% of U.S. electricity. President Obama’s fading goal of a million plug-in hybrid automobiles by 2015, meanwhile, is the proverbial “drop in the bucket,” since we have 255 million petroleum-only vehicles. Policies to achieve sustainability should appreciate that new technologies continually offer us the ability to utilize fossil fuels differently tomorrow than we do today. The U.S. National Energy Technology Laboratory, for instance, reports that next-generation technologies will make crude yielded from CO2 enhanced oil recovery 100+% “carbon free,” up from 65% today.19 With pre-recession growth trends re-emerging, this reality of oil, oil imports and technological advancement should drive any national energy strategy put forth. LITERATURE CITED

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

- Oil and gas in the Capitals (February 2024)

- What's new in production (February 2024)

- U.S. operators reduce activity as crude prices plunge (February 2024)

- U.S. producing gas wells increase despite low prices (February 2024)

- U.S. oil and natural gas production hits record highs (February 2024)

- Dallas Fed: E&P activity essentially unchanged; optimism wanes as uncertainty jumps (January 2024)

- Applying ultra-deep LWD resistivity technology successfully in a SAGD operation (May 2019)

- Adoption of wireless intelligent completions advances (May 2019)

- Majors double down as takeaway crunch eases (April 2019)

- What’s new in well logging and formation evaluation (April 2019)

- Qualification of a 20,000-psi subsea BOP: A collaborative approach (February 2019)

- ConocoPhillips’ Greg Leveille sees rapid trajectory of technical advancement continuing (February 2019)