DAVID WOOD, DWA Energy Limited, Lincoln, UK.

|

| Qatargas is using Q-Max carriers with LNG capacity of 9.4 MMcf to deliver cargoes to Europe and China. |

|

Since 2011, the future global supply of LNG looks increasingly more robust, with new supplies in planning in North America, East Africa (in particular, Mozambique and Tanzania), from the Eastern Mediterranean (Cyprus and Israel), Russia (i.e. planned Vladivostok, Shtockman and Yamal projects), and on a smaller scale from South America (i.e. Colombia), Table 1. These new supplies, as and when they appear in the market over the course of the next decade, will provide significant competition to some of the large LNG-producing nations (e.g., Australia and Qatar). Already, some of the operators of Australia’s numerous planned liquefaction projects with some of the most expensive projects on a unit cost-of-supply basis worldwide, and faced with further increases in project costs, are beginning to recognize that they need to become more cost-competitive, if they are to find long-term buyers and prosper. On the other hand, Asian LNG buyers are keen to see these potential sources of supply help to dilute the oil-indexed pricing mechanisms that are forcing Asian buyers to pay much higher prices for their gas imports than North America and Europe. Herewith is a country-by-country report of the LNG supply trends throughout the world.

|

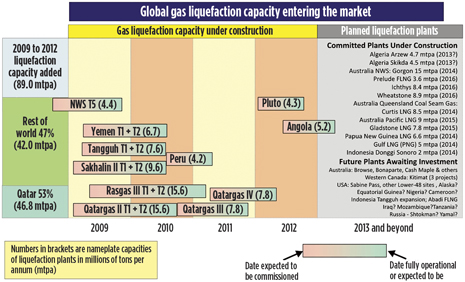

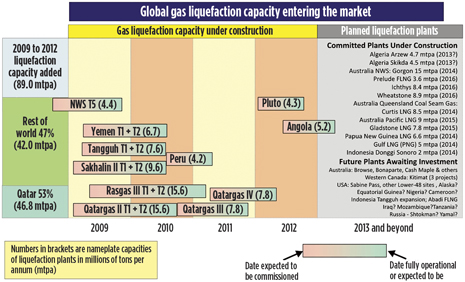

| Table 1. Gas liquefaction projects onstream in the 2009 to 2012 period and some of the projects under planning and development for 2013 and beyond. |

|

MIDDLE EAST

Qatar is now the world’s largest LNG exporter, following massive investments in infrastructure and shipping over the past 20 years. In 2011, Qatar exported 76 mt of LNG to some 20 countries, making it also the most diversified supplier. The 2011 supply from Qatar increased dramatically from the 56 mt supplied in 2010 and the 37 mt supplied in 2011, due to several new large liquefaction trains coming onstream during that period. The UK was Qatar’s single largest gas customer in 2011 with Japan, India and North Korea being its other major buyers. Qatar provided some 37% of the LNG imported into North America in 2011 (more than from Trinidad), despite diverting to Asia many cargoes due to be delivered there under long-term contracts. Demand for imported gas in the U.K. and other European destinations is, however, much lower in 2012, providing Qatar with the challenge to divert even more LNG from North America and Europe to Asia. The ability to move LNG to where the gas market is strong highlights LNG’s major strength over pipeline alternatives.

Oman operates a three-train LNG facility, which exported 8 mt in 2011, mainly to Asian buyers (50% to Japan; 46% to Korea). Oman needs to tie in additional gas resources to the Qalhat liquefaction plant to sustain or expand it s capacity. The BP-operated Block 61, large, tight gas Khazzan-Makarem field is expected to be declared commercial in 2012. The field would be developed in phases to offset decline of existing gas fields, and is anticipated to reach production of 1.2 Bcfd in 2017, and some development phase could be dedicated to expansion of the Qalhat liquefaction plant.

Yemen’s two-train 6.7-mtpa liquefaction plant has been fully operational since 2010. In 2011, Yemen exported 6.6 mt of LNG, with some 61% landed in Asia (including 42% to South Korea, which is an equity shareholder in the liquefaction plant), 21% in North America (mainly U.S.), 13% in Europe (mainly in the U.K.) and 5% to Chile. Exports in 2010 were only 4 mt, due to the second train becoming operational during the year, but landed in a similar range of locations. Yemen LNG has long-term off-take agreements landing cargoes in North America, which means it currently has to redirect many of its cargoes under short-term agreements to higher-priced Asian markets. In the first half of 2012, the feed gas pipeline supplying the Balhaf facility was sabotaged three times, as ongoing political unrest delayed the LNG export project.

Iran has been building its first liquefaction plant for several years without the involvement of international oil and gas companies. It is located between the southern port towns of Assaluyeh and Kangan, using mainly European technology and cash from Iranian banks and investors. The project is progressing slowly, and the start date has consistently been delayed. According to the project website, the plant will consist of two, parallel LNG trains, each with a capacity of more than 5.4 mtpa of LNG. The current U.S. and European sanctions on Iran’s oil exports will likely impact this project.

NORTH AFRICA

Algeria has exported LNG for decades from two liquefaction plants, both of which have new liquefaction trains under construction to replace some of the aging trains. Sonatrach is installing a 4.5-mpta unit at the Skikda export facility, with a planned start-up date in 2012 or 2013. This will be followed by a new 4.7-mtpa unit, expected to be completed at Arzew in 2013. Algeria has a policy of avoiding deals with intermediate LNG traders and aggregators where possible, which to some extent, limits its ability to divert cargoes to high-priced markets.

Egypt exported 6.3 mt of LNG in 2011, compared to 7.1 mt in 2010 and 10.4 mt in 2008. This significant decline is linked partly to declining LNG demand and prices in North America, partly to domestic Egyptian gas price indexation and the country’s revolution of 2011. Egypt maintains a diversified LNG customer base, trading with 14 countries in 2011. However, multiple attacks on its gas export pipeline to Israel and Jordan closed that export outlet in 2012, probably forever, and this has raised doubts concerning how gas exports from Egypt will now evolve.

Libya’s revolution in 2011 interrupted the re-development of its small, aging LNG export infrastructure at Marsa El Brega, which was underway. Shell subsequently announced in May 2012 that it was suspending its operations in Libya, due to rising security concerns and it is believed, difficulties in reaching commercial agreements with the new ruling authorities.

WEST AFRICA

Angola’s 5.2-mtpa first liquefaction train was commissioned in mid-2012 following construction on behalf of Angola LNG (which includes equity holdings by Sonangol, Chevron, BP, Total and Eni) by Bechtel from (2008 to 2012) of the ConocoPhillips optimized cascade technology, similar to that commissioned in Equatorial Guinea in 2007. Despite originally being sold under long-term contracts to supply the now essentially defunct U.S. LNG import market, much of the LNG produced by Angola LNG is now expected to be delivered to Asian markets.

Equatorial Guinea produces LNG from the single-train 4-mtpa Bioko Island LNG operated by Marathon Oil and its partners. That plant was built with its initial investment underpinned by long-term supply contracts including one through BG Group to the U.S. In 2007, 35% of the LNG that was exported, was landed in the U.S., with the remainder going to Asia. By 2010, no LNG was landed in the U.S., with some 61% landed in Asia and 30% in South America (particularly Chile), and the remainder going mainly to Kuwait; in 2011, 76% of the LNG exported was landed in Asia (mainly in Japan and Korea) and 24% in Chile. Substantial, additional gas discoveries in deepwater in recent years have led to a second LNG train proposal approaching its final investment decision at the end of 2012 with a different group of equity partners, i.e. Noble Energy, Ophir and Sonagas.

Nigeria has the capability to produce some 22 mtpa of LNG from the six trains of the Nigeria LNG (NLNG) plant on Bonny Island, with the sixth train onstream in 2007. In 2008, that represented some 10% of the global LNG market, and the future looked bright with potential to more than double production capacity with new projects that had progressed through their FEED studies. However, dithering and political infighting over the Petroleum Industry Bill proposed originally in July 2009 have delayed further progress in the NLNG Train 7 project, as well as the greenfield Brass LNG and OKLNG projects. Despite its expansion limitations, NLNG sustains one of the world’s most diversified LNG supply operations. It delivered almost 20 mt of LNG to 20 different countries in 2011.

EAST AFRICA

East Africa is likely to provide at least one LNG export terminal by the end of decade. Mozambique and Tanzania have reported several giant gas discoveries in the past two years in a deepwater gas trend that is lean in NGLs and likely to extend north into Kenya, Fig. 1. This new gas province is well-positioned to supply gas to Asia, and along with potential North American LNG exports, seems set to compete with high-cost LNG projects being sanctioned in Australia to supply Asian markets. Limited existing gas infrastructure, high levels of corruption and questionable fiscal stability are negative factors and hurdles for these projects to overcome.

|

| Fig. 1. Anadarko drillship conducts a natural gas flow test offshore Mozambique. |

|

RUSSIA

Russia's only LNG export facility is Sakhalin 2, located north of Japan. The combined capacity of its two trains is 9.6 mtpa. In June 2012, Gazprom and Shell announced a FEED study to possibly expand that plant to 15 mtpa by adding an additional train. East Coast Russia is a key part of Gazprom’s LNG strategy, and in July 2012, it announced a feasibility study for the construction of a 10 mtpa LNG plant near Vladivostok, to be completed by the end of 2012, with production scheduled to begin in about 2020. This followed a memorandum of understanding reached by the Russian and Japanese governments. Japan is keen for Gazprom to construct a gas pipeline to Japan, but this is unlikely to happen before a Vladivostok LNG plant is built, and it is technically uncertain, due to high seismic activity along possible pipeline routes.

Proposed Arctic coast Russian LNG export projects continue in planning, but they are hampered by technical complexity, harsh climatic conditions and uncertain long-term fiscal terms and stability. Gazprom (51%), along with Total (25%) and Statoil (24%), had planned to make the final investment decision on its long-planned Shtokman field (Barents Sea) development before the end of 2011, but this was delayed, pending tax incentive decisions. This project, involving one of the world’s largest undeveloped gas fields at 7.5 mtpa of LNG, is provisionally scheduled for 2017. Total and Statoil have expressed their desire for Russia to approve a substantial tax break for the project before they give their go-ahead and commit to the sizeable signature bonuses that are believed to be payable once the final investment decision is made. Shell announced in June 2012 that it was considering taking a stake in the Shtokman LNG project.

The Yamal LNG project, controlled by Novatek and with Total as a 20% partner, has also gained momentum in 2012, with work commencing on constructing the port at Sabetta. It is based around the development of the large South-Tambeyskoye gas-condensate field. It has the ambitious objective of seeking to export LNG to Asia via the northeastern Arctic Ocean sea route, using an ice-breaking LNG vessel. The project is expected to cost in excess of $30 billion. Novatek has reportedly been negotiating with Qatar and India for the sale of a 29% interest in the project, while it retains a 51% share (Total holds a 20% share). LNG supply is unlikely to commence before 2017, even if the final investment decision is made in 2012.

Gazprom began enthusiastically trading LNG in 2005, long before the first exports from the Sakhalin 2 liquefaction plant. By 2012, it had built a substantial LNG trading portfolio. It now buys short-term cargoes of LNG from Australia, Egypt, Qatar, Nigeria and the U.S., and has entered into long-term charter agreements for newly built LNG carriers to facilitate short-term LNG trading. In 2012, it has also entered into long-term LNG supply contracts with India.

ASIA

Malaysia exported 24.6 mt of LNG in 2011 (compared with 22.6 mt in 2010 and 21.9 mt in 2009), with 61% sold to Japan, 17% sold to Korea and 14% sold to Taiwan. Only 1.5% of Malaysia’s exported LNG was delivered outside Asia to Middle East destinations (i.e. Kuwait and/or Dubai). Petronas sanctioned in June 2012 a 1.2-mtpa floating liquefaction plant (FLNG), to be located some 112 miles off Bintulu, Sarawak, and scheduled to be the world’s first operational FLNG facility when it comes onstream in 2015. That FLNG is designed to access production from several remote, scattered gas fields.

Indonesia exported 21.6 mt of LNG in 2011 (compared with 23.2 mt in 2010 and 19.2 mt in 2009). Indonesia delivered LNG cargoes to Chile and Mexico in 2011, but 99% of its exported LNG was landed in Asia, of which 43% was sold to Japan and 37% to South Korea. Its planned new train at the Tangguh liquefaction plant will help to replace supply now terminated from the Arun facility and, supply its developing internal market for LNG.

AUSTRALASIA

Australia has $200 billion of LNG export projects in planning and under construction, and is targeting production of about 60 mtpa by 2020 (Leather & Wood, 2012). That quantity is almost triple the 2012 LNG production capacity of 24 mtpa, which includes its latest liquefaction plant to be commissioned in 2012—Woodside’s 4.8-mtpa Pluto project. In 2011, Australia exported 19.2 mt of LNG, all delivered in Asia. Australia, was in 2011, together with Nigeria, the fourth‐largest LNG exporter globally behind Indonesia and Malaysia, but well behind Qatar. By 2020, with all the projects under construction, Australia will become by far the second-largest LNG exporter worldwide.

Australia’s rapid development of its LNG industry is not without its problems, which include: significant cost inflation, impacting equipment , services and labor costs; labor disputes; disgruntled communities and land owners (particularly in the coal seam gas producing areas); indigenous people’s claims on project sites; and environmental objections concerned with above-ground and below-ground water contamination and atmospheric emissions. All of these issues are leading to an increased cost of LNG supply at a time when lower-priced LNG from new sources of gas supply in North America (and potentially from East Africa) is being offered to its key Asian LNG buyers.

Papua New Guinea continues to progress the PNG LNG project, expected to cost close to $16 billion. ExxonMobil and its partners are on track to deliver 6.6 mtpa of LNG from 2014 to long-term customers in Japan, China and Taiwan. Recent drilling is aimed at establishing gas reserves for a phase 2 expansion of the project. However, the project is not without its challenges, which include local community discontent concerning compensation and local employment issues. A devastating landslide in Hela province in January 2012, close to a quarry used for the LNG project, was reported to have killed as many as 60 people. The 407-km offshore export pipeline component of the project, taking gas to the liquefaction plant located close to Port Moresby, was completed in 2012.

A second planned liquefaction project in PNG, led by InterOil, has struggled over the past year or so to raise sufficient finance, or to persuade the PNG government that it’s phased-development approach, focused mainly on condensate recovery in combination with small-scale modular liquefaction facilities and a floating liquefaction vessel, is in the best interest of the country. In June 2012 the government put InterOil on notice that approvals for the project would be cancelled, unless it complied with original project objectives, viz. the building of a 7.6-to-10.2 mtpa liquefaction plant, based on InterOil's Elk and Antelope gas reserves, using internationally recognized technology and operators with experience at similar-sized assets. Nevertheless, it seems likely that PNG is to become a major Asian LNG exporter over the next few years with sufficient resources to grow its gas export capacity significantly in the medium term.

LATIN AMERICA

Peru LNG has the capacity to produce some 4.4 mtpa. Repsol has the exclusive marketing rights to the production from Peru LNG, with some two-thirds of that plant’s production originally allocated to Mexico’s Manzanillo terminal, commissioned in 2012. Low gas prices in Mexico, indexed to the Henry Hub benchmark, have resulted in Repsol redirecting many of the cargoes to Asian markets in 2011 and 2012.

Trinidad and Tobago believed that it had a secure LNG market in the U.S. until a couple of years ago. In 2007, it exported 13.6 mt, with 70% of that landed in the U.S. The Trinidad government and its LNG operators began to divert LNG exports to other markets to make up for lost revenue and U.S. market share as gas prices there collapsed. In 2011, it exported 14.2 mt, with only 25% of that landed in North America (i.e. U.S. and Canada), with the remainder landed at some 17 different destinations around the globe, including 32% to Latin America and the Caribbean (particularly Argentina and Chile); 20% to Europe (particularly Spain); and, some 20% to Asia (particularly South Korea).

Colombia has become the first country to sanction the building of a Floating Liquefaction Regasification & Storage Unit (FLRSU), to be located on its Caribbean coast. Pacific Rubiales Energy announced in 2012 an agreement with Exmar to build, operate and maintain the small-scale FLSRU, with a design capacity of 695 MMscfd (approximately 0.5 mtpa per annum) over a 15-year period, under a tolling structure, possibly starting in late 2014. The gas will be supplied from La Creciente gas field, and the LNG produced will be marketed initially in the Central America/Caribbean region.

NORTH AMERICA

The growing disparity between North American natural gas prices and rates in European and Asian markets has already fuelled the trade in re-exported LNG from the United States. However, the U.S. remains a net importer of gas (mostly via pipeline from Canada and Mexico), with net imports amounting to 98 Bcm in 2011. This has led many gas consumers in the U.S. to express concerns about the long-term wisdom of exporting large quantities of gas as LNG from a long-term security-of-supply and price perspectives. The potential of substantial exports of shale gas LNG from North America is likely to place downward pressure on Asian LNG prices from 2015. That prospect is causing high-cost LNG suppliers, such as Australia, some concern. However, there is much enthusiasm from the main Asian LNG buyers.

Canada has lost about one-third of its gas export market to the U.S. in the past four years, and its gas producers are struggling to overcome low prices and much-reduced demand for their gas. Consequently, several projects are in the advanced stage of planning to export gas in the form of LNG from liquefaction plants on the coast of British Columbia. This requires the construction of gas pipelines across the Rocky Mountains to link the shale gas and conventional gas resource basins in Alberta and British Colombia to the Pacific Coast.

Shell, with the aid of buyers and equity partners Mitsubishi, CNPC and Kogas, is planning to build a 12-mtpa liquefaction plant (as phase 1 of the project) near Kitimat, at a cost of $12 billion plus $4 billion for the pipeline.

Canada's NEB has already awarded LNG export licenses to two planned liquefaction projects near Kitimat: Kitimat LNG, backed by Apache, Encana and EOG Resources (the final investment decision on that project was delayed in 2012, pending agreements with gas buyers).

The United States has exported LNG from the Kenai plant in Alaska for more than 40 years. That small, aging liquefaction plant is imminently due to close, due to lack of available gas in the Cook Inlet, but it continues to supply intermittent cargoes during 2012. The demise of the gas export pipeline projects, pursued by the North Slope gas operators and the State of Alaska for many years, to take gas from Alaska to the Lower-48 states occurred in 2011, as gas prices fell way below the transit tariffs such a facility would require. Subsequently, the main gas resource holders of the North Slope (i.e. ExxonMobil, BP and ConocoPhillips) have proposed a trans-Alaskan pipeline project to supply a gas liquefaction plant, to be located at Valdez. Studies for the feasibility of this project are ongoing. It faces significant issues, particularly regarding cost and an agreement on an appropriate fiscal design. Under the current Alaska state fiscal design, the state would likely earn less total fiscal revenue when gas sales begin, as its high costs would dilute taxes paid for oil revenues (Dickinson & Wood, 2009). On the other hand, the major investors in an Alaska LNG supply chain are likely to demand some fiscal clarity and incentives before making their final investment decision based upon Alaska’s track record of fiscal instability.

The expansion of the Panama Canal is underway, and it will double its capacity by 2014, making it able to take standard-sized LNG carriers. This development will make the LNG supply chain from the U.S. Gulf of Mexico to Asia more cost-effective by reducing the distance significantly, as most re-exported cargoes are currently sailing from the Gulf of Mexico around South Africa to reach Asia. Hawaii, located en route, is also looking to become an LNG importer and may provide an additional market for mainland U.S. gas.

As of second-quarter 2012, at least nine separate potential LNG export projects (including the Cameron, Freeport and Lake Charles facilities in the Gulf of Mexico) had applied to the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) to export collectively more than 105 mtpa of domestically produced LNG (i.e. excluding re-exports of imported LNG). However, the only project to have obtained approval to export to both free-trade agreement (FTA) and non-FTA countries (i.e. outside of North America) is Cheniere Energy’s Sabine Pass terminal. While the DOE approved Cheniere Energy's plans, the Obama administration has delayed the final say of the other applications from at least eight other companies until the results of a study that analyzes how allowing companies to export might impact natural gas prices in the U.S. The results of that study are due in mid-2012, but decisions may be delayed until after the U.S. presidential elections.

Cheniere Energy has been approved to build a liquefaction facility with a capacity of up to 18 mtpa and a 20-year license to export LNG, Fig. 2. Plans for the plant include four modular LNG trains, each of 4.5-mtpa capacity to be built in succession nine months apart, with the first train due onstream in 2015/2016. The final investment decision for the project depends partly on finalizing a financing arrangement, and Cheniere managed to secure a $3.4-billion financing facility for the project in July 2012.

|

| Fig. 2. Cheniere Energy’s Sabine Pass LNG terminal is awaiting a final investment decision. |

|

Some 89% of the LNG from the Sabine Pass export project has been sold under long-term contracts to four buyers: BG Gulf Coast LNG (5.5 mtpa) and Gas Natural Fenosa (3.5 mtpa) have secured rights to production from the first two trains; and, Kogas (South Korea) (3.5 mtpa) and India’s GAIL (3.5 mtpa) have secured rights to production from trains three and four, due to start production in 2017/2018.

LNG exporters from the U.S. are typically not part of vertically integrated supply chains, as they are in many parts of the world.

Typically, the U.S.-based liquefaction companies are following a model of purchasing gas from domestic producers at a price closely indexed to the Henry Hub price. To reduce downside price risk, some companies are negotiating LNG sales contracts linked to the Henry Hub price plus a fixed cost associated with life cycle liquefaction plant costs and shipping costs. Based on Cheniere Energy’s contract terms as reported, at a Henry Hub price of US$3/MMBtu (the Henry Hub price in late July 2012), LNG from the U.S. could be delivered into East Asia at a price of around $9/MMBtu or Europe at $7/MMBtu. This is highly competitive, particularly in Asia, and is causing concern for other conventional gas/LNG suppliers to the region.

CONCLUSIONS

The LNG industry in 2012 is mature, in the sense that it is diversified on the supply and demand side. LNG is also flexible and capable of responding to short-term changes in market conditions, exploiting arbitrage opportunities, and competing effectively with pipeline in terms of price and cost of supply in several markets. New, innovative floating technologies are opening up new market opportunities and supply chains for the LNG sector.

The natural gas resource base, because of unconventional gas resources and multi-stage fracing technologies, is growing, which make gas supply chains more sustainable and the long-term viability of the LNG sector more secure. However, the LNG sector does need to do more to resolve disputes with certain communities and to convince the wider energy consumers of the benefits of its product compared to alternative energy sources such as coal and renewable energies, to secure larger shares of primary energy supply. It is within reach for natural gas to become the primary energy over the next decade, where the LNG sector can play a big part.

REFERENCES

1. Australian Government, 2012. Gas market report. Bureau of Resources and Energy Economics (BREE) (July), pp.74.

2. BP, Statistical Review of World Energy, June 2012, 45 pages.

3. Dickinson, D.E. and D. A. Wood, “Alaska tax reform: Intent met with oil (Part 1 of 2), Oil & Gas Journal, May 29, 2009, pp 20-26.

4. Leather, D.T.B. and D. A. Wood, “Maintaining momentum in Northern Australia's LNG projects faces formidable CSR challenges,” Oil, Gas & Energy Law Intelligence, Vol. 10 (3), 2012

5. U.S. Government, Energy Information Administration, Natural Gas Monthly, June 2012.

6. Wood, D.A., A Review and Outlook for the Global LNG Trade, Journal of Natural Gas Science & Engineering, Volume 9, November 2012, pp 16 -27.

The authors

DAVID A. WOOD is the principal consultant of DWA Energy Limited, UK, specializing in the integration of technical, economic, fiscal, risk and strategic information to aid portfolio evaluation and project management decisions. Dr. Wood has more than 30 years of international oil and gas experience spanning technical and commercial operations, contract evaluation and senior corporate management. /dw@dwasolutions.com. |

|