|

JERRY GREENBERG, Contributing Editor

|

| The Noble Discoverer drillship (left) is drilling top hole sections in the Chukchi Sea for Shell. Gazprom’s Prirazlomnoye field development in the Pechora Sea (center) was scheduled to be onstream during fourth-quarter 2012, but this was pushed back another year to September or October 2013. The drilling, production, oil storage and offloading platform has been idle in the Pechora Sea since 2011. The Geo Explorer (right) acquires seismic data offshore northeast Greenland for ION Geophysical. Since 2009, the company has conducted a number of under-ice Arctic projects in the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas, and the high Arctic offshore Russia. |

|

The Arctic is one of the hot spots, so to speak, in the global drilling effort. In 2008, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) estimated that 90 billion bbl of undiscovered, technically recoverable oil, 1,670 Tcf of technically recoverable natural gas and 44 billion bbl of technically recoverable natural gas liquids (NGLs) were contained in the area north of the Arctic Circle. The assessment noted that about 84% of estimated resources were offshore. These resources, according to the USGS, account for 22% of the undiscovered, technically recoverable global resources, including about 13% of undiscovered oil, 30% of undiscovered natural gas and 20% of undiscovered NGL.

The USGS’ assessment also said that more than 70% of the mean undiscovered oil resources is estimated to occur in five provinces worldwide: Arctic Alaska, Amerasia basin, East Greenland Rift basins, East Barents basins and West Greenland/East Canada. Additionally, the USGS continued, more than 70% of undiscovered natural gas is estimated to occur in only three provinces: the West Siberian basin, the East Barents basins and Arctic Alaska.

It’s no wonder, then, why independent operators and national oil companies around the world are spending billions of dollars, and many years planning and exploring, in the world’s harshest environments to gain a share of these resources.

The USGS also noted that by 2008 a number of onshore areas in Canada, Russia and Alaska were explored and developed, resulting in the discovery of more than 400 oil and natural gas fields north of the Arctic Circle. Those fields accounted for about 240 billion bbl of oil and oil-equivalent natural gas, nearly 10% of the world’s known conventional petroleum resources.

IS ARCTIC DRILLING SAFE?

That depends upon who is asked. If you’re Total, the UK Parliament or the European Commission’s Environment Committee, it probably is unsafe. If you’re a Norwegian government official, you are likely going to continue drilling the Arctic. In fact, you are going to be offering new leases in the Barents Sea next year. So is the government of Greenland, which will be offering new licenses along its east coast.

Several organizations, oil companies and governments are opposed to continued Arctic drilling activity until it can be proven to be safe. Total CEO Christophe de Margerie said, for example, that oil exploration in the Arctic could be a costly disaster in terms of damage to the environment as well as for the company conducting the exploration. Interestingly, Total is Gazprom’s partner in the Shtokman project in the Barents Sea, which is not an issue, apparently, because the Shtokman project is a natural gas development.

Additionally, several members of the UK Parliament have proposed to stop all Arctic drilling until more stringent safety standards can be implemented. Parliament’s Environmental Audit Committee noted that more rigorous standards also include increased financial guarantees, as well as a standard concerning spill response efforts.

The European Parliament’s Environment Committee attempted to introduce a moratorium on offshore drilling in the Arctic, an effort that the Industry Committee rejected. However, the Industry Committee did say that, like the UK Parliament, oil and gas companies should have the financial security to handle any liability resulting from accidents and oil spills.

Norwegian governmental officials, in the meantime, said that the EU has no jurisdiction in the Arctic. Norwegian Petroleum Minster Ola Borten Moe was reported to have said that Norway’s boundaries end almost at the North Pole. The government is in the midst of its 22nd licensing round, which illustrates the industry’s heightened interest in the Arctic. In 2011, the government awarded 34 North Sea licenses and four in the Barents Sea. The present licensing round includes 86 blocks in the frontier areas, including 72 in the Barents Sea and 14 in the Norwegian Sea. A licensing round for mature areas includes 48 blocks, with 33 in the Barents Sea, 12 in the Norwegian Sea and two in the North Sea.

EXPLORATION, DEVELOPMENT ALL AROUND THE ARCTIC CIRCLE

Much of the news recently has been about Shell’s more than six-year effort to begin drilling in the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas off Alaska. It’s almost a story of “one step forward and two steps back,” but the operator finally began drilling top hole sections of several wells in the Beaufort. ConocoPhillips, Chevron and others are planning exploration in the Alaskan Arctic region during the next couple of years; however, Statoil, which partnered with ConocoPhillips, is postponing its drilling plans there until it sees how Shell’s efforts pan out. It’s not known whether this decision will significantly impact ConocoPhillips’ drilling plans.

Drilling also continues along Greenland’s west coast in Baffin Bay with relatively little success, while the government is offering 19 new offshore licenses off the east coast to be awarded in 2013. Cairn Energy, with partner Statoil, is one of the most active operators along the west coast, but the firm has little to show for its efforts.

Russian companies Rosneft and Gazprom are very active in their country’s Arctic regions. Rosneft, particularly, seems to announce a new joint venture E&P program with western operators almost weekly. Gazprom also was busy with its Shtokman field in the Barents Sea, but the company will have more time on its hands, now that it postponed the project indefinitely. Gazprom also has its Prirazlomnoye field in the Pechaora Sea and continuing successes at the Sakhalin projects in the Sea of Okhotsk, among other prospects, to take up its time. Rosneft also is active in the Okhotsk Sea, as well as the Kara Sea and Black Sea.

There is some activity in the Canadian Beaufort Sea and Arctic Islands. The Norwegian Arctic region could see increased drilling activity. The government is planning a licensing round that offers more than 70 blocks in the Barents Sea, stretching to the Arctic Circle and beyond. Future license rounds also could include Barents Sea blocks to the extreme north of the country.

Despite news of apparent increases in Arctic drilling and production activity, not all of it is good news. Some major oil and gas companies say the industry should put a hold on its Arctic drilling plans. The European Union recently disagreed, voting contrary to one of its committees, which recommended putting Arctic drilling activity on hold for a while. The UK government also joined in calling for a drilling moratorium in the Arctic.

U.S. ARCTIC DRILLING TO BEGIN ANEW

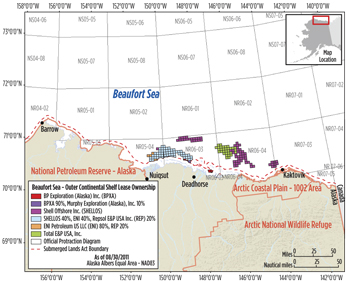

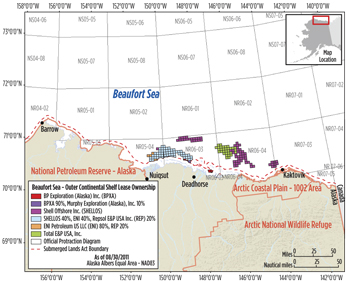

After about half-a-dozen years and billions of dollars, Shell was prepared to finally begin exploratory drilling in the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas this year, but events continued to work against the operator. Now, rather than drilling to its geologic objectives, Shell is approved only to drill the top hole sections in preparation for exploratory drilling in 2013, Fig. 1.

|

| Fig. 1. Beaufort Sea lease ownership map. Source: BOEM. |

|

Shell is no stranger to high-risk drilling programs. The company, along with numerous other operators, such as Exxon, Arco, Amoco, Tenneco, BP and Encana, drilled a total of 30 wells in the Beaufort Sea from late 1981 until early 2003. The industry began drilling from man-made gravel islands in about 20 ft of water, and later moved into water depths between 50 and 60 ft before turning to larger mobile units such as Global Marine’s Glomar Beaufort Sea concrete island drilling system (CIDS) in the mid-1980s.

Canadian Marine (Canmar) operated several drillships (Canmar Explorer II in the Beaufort and Canmar Explorer III in the Chukchi Sea) while Beaudrill operated its Kulluk mobile Arctic drilling rig, the same unit that Shell is using today in its Beaufort Sea drilling program. Beaudrill sold the Kulluk to Canmar, which sold it to Amoco in 1993, which sold it to Seatankers in 1997, which sold it to Shell in 2005.

Despite the very large mobile drilling units, the industry rarely drilled in water depths greater than about 100 ft. The Kulluk drilled one well in 167 ft of water, and the Canmar Explorer II drilled in 166 ft of water. Shell is drilling in about the same water depths today.

Even fewer wells have been drilled in the Chukchi Sea, with Shell drilling five of the six wells drilled between 1989 and 1991. Chevron was the operator of the remaining well drilled in the Chukchi Sea. Interestingly, one of Shell’s wells drilled from September 1989 to August 1990 was its Burger well with the Canmar Explorer III drillship in about 150 ft of water, the same prospect that the Noble Discoverer drillship has been drilling since September this year.

The Kulluk is drilling Shell’s Sivulliq prospect at the same time, the first time in more than two decades that two rigs are drilling simultaneously offshore Alaska.

It’s been a long path to that end, working through more than six years of obtaining necessary permits and approvals, only to encounter several issues just before finally beginning scheduled drilling. As Shell began moving closer to spud day for both projects, several setbacks occurred, preventing the rigs from drilling into hydrocarbon-bearing zones during 2012. Shell was not authorized by the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) to drill into oil-bearing zones until it tested and certified a spill-containment system. BSEE did authorize the company to commence preparatory activities that include creating a mudline cellar to protect the blowout preventer (BOP) from the ice that may scour the seafloor.

In late August/early September, the Noble Discoverer was connected to a pre-set anchor system and began drilling its first Chukchi Sea well in the Burger prospect on Sept. 9. The next day, the decision was made to move the rig off location, due to potentially encroaching sea ice. The rig was moved back to the wellsite around Sept. 20.

Meantime, during September, Shell completed a series of tests of the industry’s first Arctic containment system. During a final test, however, the containment dome aboard the Arctic Challenger barge was damaged, and the operator was assessing the damage and the dome’s readiness for deployment.

ConocoPhillips, in a plan of exploration filed in August 2011, said it proposed to drill as many as two exploration wells in the Devils Paw prospect in Colbert Area NR03-03 of the Chukchi Sea during open-water conditions. Operations would include drilling rig mobilization, air support supply operations, drilling operations, and end-of-season operations. Monitoring activities are ongoing.

ConocoPhillips holds 98 lease blocks in the Chukchi Sea, distributed throughout the general area where Shell and Chevron drilled a total of five exploration wells between 1989 and 1991. Fifty of the 98 lease blocks surround the Klondike well that Shell drilled in 1989. ConocoPhillips refers to these 50 lease blocks as the Devils Paw prospect. The proposed drill sites are approximately 120 mi west of Wainwright. The prospect is in about 140 ft of water. It is anticipated that the drilling program would span 120 days during the summer and fall of the drilling season in the first year of exploration, planned to begin in 2014.

Earlier this year, ConocoPhillips and Keppel Offshore & Marine Technology jointly designed a first-of-its-kind ice-worthy jackup rig to drill in the Arctic, presumably in the operator’s Chukchi Sea drilling program. The rig would have dual cantilevers to optimize drilling within a limited time frame. It would be capable of operating in a self-sustained manner for 14 days and be equipped with a hull designed for towing in ice. It would also be able to resist the impacts from multi-year ice floes and ridges, as well as withstand certain levels of ice thickness. This joint design project is expected to be completed by the end of 2013.

Statoil holds 16 operated leases in the Chukchi Sea, a result of the 2008 Chukchi Sea lease sale, the latest sale held for federal Alaskan acreage. 3D seismic was acquired over its prospects in 2010 and 2011. The company also farmed into ConocoPhillips’ leases in the Devil’s Paw prospect. Statoil planned to drill its first well in 2014. However, Statoil threw a wrench into the works, when it said it would wait and see how Shell’s efforts pan out before finally committing to its own Arctic Alaska programs. Statoil is moving back its Chukchi Sea exploration at least a year to 2015, as it watches Shell’s path through a regulatory and technical maze. Statoil’s decision to push back its exploration program was made before Shell neared the end of that journey and began drilling top hole well sections.

Statoil will move ahead with several of its other Arctic drilling programs, including the Canadian Beaufort Sea, Greenland, Barents Sea, and several Norwegian projects and prospects. In the Canadian Beaufort Sea, Statoil and Chevron agreed to a farmout of Chevron’s acreage and began a 3D seismic program this summer over a 2,060-sq-km area of Block EL 460 in water depths ranging from 800 to 1,800 m (2,600–5,900 ft). Chevron is operator with 60%, while Statoil will hold the remaining interest.

RUSSIAN ARCTIC ACTIVITY

Gazprom and Rosneft, along with the companies’ various partners, are among the most active operators in the Russian Arctic along the country’s continental shelf, as well as other Arctic regions. Gazprom’s largest Arctic projects include Shtokman field in the Barents Sea and Prirazlomnoye field in the Pechora Sea. The company also is active in the Sakhalin II and III projects in the Sea of Okhotsk.

Prirazlomnoye field, discovered in 1989, is about 60 km offshore, in water about 65 ft deep. Reserves are reported at about 530 million bbl. The field will be developed with an ice-resistant drilling/production unit from which the company plans to drill 40 directional wells. However, like many other Arctic drilling and production projects, the Prirazlomnoye project has experienced numerous delays and cost overruns, reportedly bringing total cost, to date, to as much as $5 billion. The company was granted tax breaks last July. It was scheduled to be onstream during the fourth quarter of this year, but it has been pushed back another year to September or October 2013.

Gazprom’s Shtokman field development also has encountered setbacks. The Barents Sea gas field, discovered in 1988, lies in water depths of about 1,080 ft. Reserves have been estimated at 3.8 Tcm of natural gas and more than 37 million tons of gas condensate. Partner Statoil decided to pull out of the development last summer, relinquishing its 24% interest back to Gazprom, and take a $338-million write-off of the project as a result of the development scheme being considered commercially unviable. Statoil could rejoin the partnership in the future. Total is Gazprom’s remaining partner, and also Shell may be interested in partnering in the project.

All of this could become moot, as Gazprom indefinitely postponed the development project, due to high costs and huge challenges in the harsh environment. Unlike the Prirazlomnoye project, Shtokman has not received economic incentives in the form of tax breaks.

Rosneft began geological exploration in its Prinovozemelsky 1 and 2 license blocks in the Kara Sea this summer, shooting 3,000 sq km of 3D seismic at the East Prinovozemelsky 1 Block with three seismic vessels. Also, 2D seismic will be conducted over 5,300 sq km of the East Prinovozemelsky 2 Block. ExxonMobil signed a strategic cooperation agreement with Rosneft for exploration in the Kara and Russian Black Seas, including the Prinovozemelsky 1, 2 and 3 license blocks. Initial cost of preliminary exploration is estimated at more than $3.2 billion. A well is planned to be drilled in 2014. The license area covers 31 million acres in water depths ranging from 120 to 1,000 ft. Sea ice covers the area 270–300 days a year, Rosneft said.

As part of the agreement, Neftegaz Holding America, an indirect Rosneft subsidiary, will have the rights to acquire a 30% interest in 20 of ExxonMobil’s Gulf of Mexico blocks. Additionally RN Cardium Oil, another Rosneft subsidiary, acquired a 30% stake in ExxonMobil’s Harmattan acreage in the Canadian Cardium formation in Alberta, Canada, an unconventional oil play.

Rosneft and ExxonMobil in September announced the selection of Vostochniy Offshore Structures Construction Yard to conduct a concept evaluation and feasibility study for a platform capable of exploring East Prinovozemelsky License Blocks 1, 2 and 3. The study will evaluate the feasibility of utilizing a gravity base structure that could extend the drilling season by several months. The structure would be designed to operate in up to 60 m (200 ft) of water.

In other agreements, Eni reached an agreement with Rosneft for joint exploration of Barents and Black Sea blocks, and for Rosneft to participate in certain of Eni’s international projects. The agreement calls for a joint venture to explore Fedynsky and Central Barents Sea fields and Western Chernomorsky field in the Black Sea. Eni holds a one-third stake in the joint venture projects.

Rosneft estimates the blocks to hold recoverable resources of 36 billion bbl of oil equivalent (boe). The operator said the Barnets Sea fields are “very” promising, due to their proximity to an area offshore Norway in which three fields have been discovered. The company also noted that seismic data and recent discoveries in the Romanian sector of the Black Sea could portend that oil and gas would be found in Western Chernomorsky field.

The government instituted tax incentives for offshore production, including a cancelling of export duties and introducing a reduced Mineral Extraction Tax rate of 5–15%, depending upon project complexity. The government also guaranteed that the favorable tax regime would remain in place for a prolonged period.

The Fedynsky Block is in the ice-free southern Barents Sea in water depths of 650–1,050 ft. Rosneft said 2D seismic located nine promising formations holding total recoverable hydrocarbon resources of 18.7 billion boe. Exploration of the field is long-range. License conditions include 6,500 km of 2D seismic before 2017, and 1,000 sq km of 3D seismic by 2018.

The Central Barents Block adjoins Fedynsky to the north in water depths ranging from 525 ft to about 1,000 ft. Seismic work at the block identified three promising formations holding total recoverable hydrocarbon resources of more than 7 billion boe. License requirements call for 3,200 km of 2D seismic to be performed by 2016 and 1,000 sq km of 3D seismic by 2018. The first exploration well is to be drilled by 2021, and if successful, a second exploration well is to be drilled by 2026.

The Western Chernomorsky block covers an area of 8,600 sq km in water depths ranging from about 2,000 ft to nearly 7,400 ft. Rosneft has carried out seismic and identified six promising formations holding total recoverable resources of approximately 10 billion boe. Two exploration wells are to be drilled in 2015–2016, in line with license conditions.

In other Rosneft partnership agreements this year, Statoil will finance geological exploration in the Perseevsky license in the Barents Sea.

NORWEGIAN ARCTIC EXPLORATION MOVES AHEAD

Statoil said on its website that it would drill nine wells during 2013 in the Norwegian Barents Sea and plans to increase its Arctic technology research budget from NOK 80 million in 2012 to NOK 250 million in 2013. The company noted that of the 94 exploration wells drilled in the Barents, it had drilled 89 of them.

Statoil will begin its 2013 drilling program in the Skrugard area in December 2012, and drill and complete four wells over a six-month period in the Nunatak, Savl and Iskrystall prospects, and a prospect to be named. The operator made two oil discoveries there, the Skrugard in 2011 and Havis in 2012, proving 400–600 million bbl of recoverable oil. Statoil is operator with 50% in each license, with partners Eni Norge (30%) and Petoro AS (20%).

Three wells also will be drilled in the Hoop frontier exploration area, the northernmost wells ever drilled in Norway. The program will continue in the Hammerfest basin close to the Snohvit and Goliat discoveries. Snohvit is the first LNG plant in Europe. Subsea development and production is tied back to an onshore plant through a 143-km pipeline.

In the Goliat area, Eni Norge (65%) and Statoil (35%) are developing the prospect with Sevan Marine’s floating production, storage, offloading (FPSO) Goliat, Fig. 2. It will be the first oil field to begin production in the Barents Sea, according to Eni. Subsea templates are connected to the FPSO, and Statoil plans to drill a total of 22 wells from eight templates. Production start-up has been pushed back to third quarter 2014, due to delays in delivery of the FPSO. The investment cost for the development has balooned 20% to $6.5 billion.

|

| Fig. 2. Eni Norge and Statoil are developing the Goliat prospect with Sevan Marine’s FPSO Goliat. It will be the first oil field to begin production in the Barents Sea. |

|

The Sevan 1000 concept is designed for Barents Sea conditions and introduces new winterization systems, Fig. 3. It is also equipped to meet the strict environmental requirements stipulated for operations in the Barents Sea. A new concept for off-loading from the Goliat FPSO and loading onto shuttle tankers has been developed, making it possible to carry out operations around the entire circumference of the platform.

|

| Fig. 3. The startup of Goliat field in the Barents Sea off Norway was scheduled for the end of 2013, but this was pushed back a year due to delays in construction of the FPSO. The vessel is designed for loading oil onto shuttle tankers from around the entire circumference of the platform. Source: Eni Norge. |

|

Lundin Petroleum has made several discoveries in the Barents Sea, its most recent with exploration well 7220/10-1 in license area PL533, with the discovery of gas condensate in the Salina structure on the west flank of the Loppa High. Well 7220/10-1 proved two gas columns in sandstone of Cretaceous and Jurassic age. Data acquisition has proven good reservoir quality in the sandstone.

In early October, Lundin spudded well 7120/6-3 S in PL490 on the Snurrevad-Juksa prospect in the Barents Sea. The well is 10 km to the northwest of Snøhvit field. The well’s main objective is to prove the presence of hydrocarbons in lower Cretaceous/upper Jurassic reservoirs. Lundin Norway AS is operator of PL490 with 60% interest. Partners are Noreco Norway AS and Spring Energy Norway AS with 20% interest, each.

GREENLAND HAS OIL, BUT HOW MUCH?

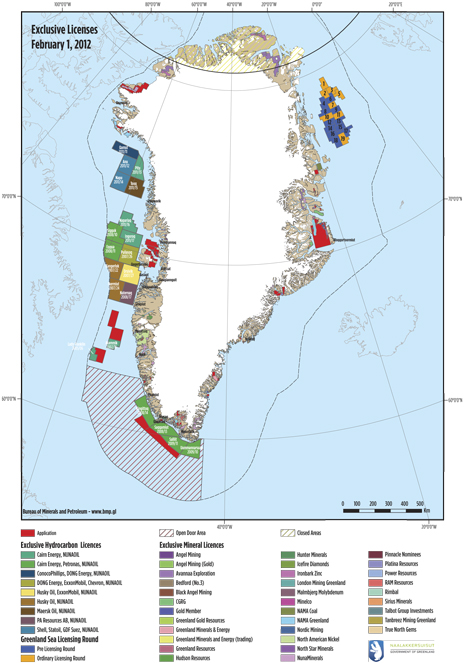

Exploratory drilling has taken place off the west coast of Greenland for many years. Cairn Energy is one of the more active companies, which also include Chevron, ConocoPhillips ExxonMobil, Husky Oil, Maersk, Petronas, Shell and Statoil, among others, whether as primary leaseholders or partners. The Greenland government will be offering new licenses off the east coast during 2013.

ConocoPhillips was awarded a license for Block 2 in Baffin Bay in 2010 along with two partners, DONG and Nunaoil. The block is the northernmost concession in Baffin Bay. Planned activities during 2012 included field work, environmental assessments and seismic acquisition. The company anticipates having 3,000 km of 2D seismic this year. ConocoPhillips also is part of a consortium to drill a series of stratigraphic wells using the scientific drillship Joides Explorer. The company said it would decide by the end of 2014 to either move ahead with drilling an exploration well or halt its operations there.

The company, meantime, said there is little doubt that Greenland contains oil, but the question is whether it would be found in commercial quantities and in good reservoirs.

Cairn completed an eight-well exploration program during 2010 and 2011, which failed to locate commercial quantities of oil. The company said in late 2011 that only 14 exploration wells had been drilled offshore Greenland at that time, including five during the 1970s, one in 2000, three in 2010 by Cairn, and five in 2011 by Cairn.

|