MARK C. THURBER and DAVID R. HULTS, Stanford University Program on Energy and Sustainable Development

|

| Symbolized by its CENPES Research Center, which was doubled in size by an expansion in late 2010, Petrobras is an example of an NOC that has taken risks in the pursuit of technology development. |

|

National oil companies (NOCs) often behave in strikingly different ways from one another and from private, international oil companies (IOCs). Given that NOCs control about three-quarters of world oil reserves (Table 1) by equity share, their variation in corporate strategy has important implications for the world oil market. The recently released book, Oil and Governance: State-owned Enterprises and the World Energy Supply,1 which we co-edited (along with our colleague, David Victor) and contributed to, explores the variations among NOCs through 15 detailed case studies and several cross-cutting pieces. Building off the research in that book, our aim in this article is to discuss the differences among NOCs in their approach to risk and why they matter.

| Table 1. Sample NOCs—Claimed oil reserves, billion bbl |

|

|

UNDERSTANDING RISK

The notion of risk encapsulates both the likelihood of a negative outcome (e.g., of drilling a dry hole) and the loss that such an outcome would entail (e.g., the investment in an exploration well).2 Risks are pervasive in the oil industry because of the enormous sums of money on the line and the significant uncertainty around whether investments will prove successful. In this article, we suggest that the goals of the state and its tools of governance may cause an NOC to tend toward one of three types of behavior: risk avoidance, risk taking or risk management. We find that each of these three approaches to risk can be useful or counterproductive for the state depending on the context. (We note, before proceeding, that these approaches to risk represent generalizations. An NOC may take risk in one situation and avoid it in another. Our argument concerns broad tendencies only.)

STATE GOALS AND NOC RISK ATTITUDE

The goals of the state are the starting point for understanding an NOC. Unlike private shareholders—which generally prioritize profit maximization above all else—governments frequently layer non-commercial objectives on top of commercial ones. NOCs may be enlisted to provide broadly popular, and costly, benefits to the population, like subsidized fuel (as in many producer states throughout the Middle East, Asia, Africa and South America) or development programs (as in Venezuela). Where a country’s tax base is underdeveloped, NOCs may supply a large portion of the revenue to fund government budgets (as in Mexico, Venezuela, Nigeria, Angola, and various Middle Eastern and North African states). Countries like Saudi Arabia, whose economic future is inextricably tied to oil, may value their NOC for its ability to inject oil into the market at whatever rate its leaders view as most beneficial over the long term. Employing a country’s nationals at the NOC is another popular governmental goal (as in Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, China and other countries). Some hydrocarbon-rich governments view oil as a stepping stone to development of high-skill industrial capability, and they may attempt to use their NOCs accordingly (as in Norway).

Governments have imperfect tools for incentivizing their NOCs to pursue the desired mix of commercial and non-commercial objectives. In the language of economics, governments must overcome a “principal-agent” problem in directing their NOC. The objectives of NOCs do not perfectly match those of their governmental masters, nor is information perfectly shared between agent and principal. A government must, therefore, choose from a variety of carrots and sticks to attempt to make the NOC do its bidding.3 With the government as majority or full owner, some tools used by the private sector are not available. Notably, NOC managers face little danger of either takeover or bankruptcy, the threat of which in the private sector tends to motivate better financial performance. (Indeed, the state may step in to prevent insolvency, if necessary, through infusions of tax revenues—the so-called “soft budget constraint”.) For fully state-owned companies, there is also no stock price to provide competitive benchmarking of NOC performance (and possible indexing of manager compensation).

CONTROLLING THE NOC

Depending on their goals and the nature of existing state institutions, governments may use different approaches to control their NOCs. We focus on two in particular: “procedure-heavy” and “monitoring-heavy” governance of the NOC. In a prototypical, “procedure-heavy” governance system, the government has the power to approve, or review in advance, major and sometimes minor NOC decision-making. When such approval authority covers NOC budgets and expenditures, it can have a particularly important effect on how the NOC does business. “Monitoring-heavy” governance systems, by contrast, delegate much of the decision-making power to the NOC and monitor the NOC’s performance ex post. Such systems may more closely approximate the corporate governance of IOCs.

These methods for controlling NOCs, and the various goals that states pursue, lead to significantly different approaches to risk on the part of the NOC. Some states, for example, want their NOCs to take the lead in developing domestic oil resources, and choose to rely on monitoring-heavy governance to achieve this outcome. Such a strategy may incentivize the NOC to take risks. Other states prioritize revenue generation and prefer to outsource much of the risk to IOCs, encouraging their NOCs to partner with private firms and overseeing the companies through monitoring- or procedure-oriented governance, Fig. 1.

|

| Fig. 1. Estimated fraction of combined oil and gas working interests in production that were self-operated in 2008. This figure shows a propensity to partner for the sample of 15 NOCs studied in Oil and Governance, as well as six major IOCs. Data source: Wood Mackenzie.4,5 |

|

SUCCESSFUL RISK AVOIDANCE IN ANGOLA

Among the more successful adopters of the risk-averse approach are Angola and its NOC, Sonangol. Between 1976 and 2002, Angola’s MPLA government depended critically on oil revenues to prosecute a civil war and, thus, could not tolerate the risk that revenues would fall short of potential.6 Accordingly, the government used Sonangol as a sector manager and regulator during this period, transferring all of the risk of finding and extracting oil to the IOCs who were best-suited to absorb it. This approach also facilitated effective monitoring of the sector through the creation of competition among IOCs. Only recently has Sonangol begun to develop its own operational capability, with the additional assumption of risk that this decision entails. A number of governments across Africa and Asia find themselves stewards of newly-discovered hydrocarbons7; many that use NOCs might be wise to incentivize these companies to avoid risk, as Sonangol has done.

A distinct advantage for Angola in pursuing a strategy of skillful risk avoidance through Sonangol was the fact that its ruling MPLA government faced little political competition (though there was military competition during the civil war). As a result, the tight-knit ruling elite could manage the NOC through personal connections with NOC senior leaders.8 The relative absence of prescriptive rules allowed the company to play wide-ranging roles in pursuit of governmental goals.

RISK AVOIDANCE BACKFIRES IN NIGERIA, MEXICO

A less successful example of risk avoidance is Nigeria, which also depends heavily on oil revenue to fund its government. However, it lacks the long political time horizons of Angola, and features a fragmented, procedure-based governance system that requires high-level approvals for even minor expenditures.9 Nigeria’s NOC, Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC), limits financial risk to the government in one way by relying on IOCs for all significant operational functions in oil and gas. Unfortunately, Nigeria’s byzantine governance structure for oil introduces massive costs and, in the process, significantly erodes net revenue to the state. While strict approval thresholds might seem to reduce opportunities for public mismanagement and graft, in practice they have the opposite effect by multiplying the number of approval gates whose gatekeepers stand to benefit. (We observe in a number of cases that procedurally-oriented efforts to fight corruption wind up feeding it while paralyzing decision-making in the process.)

Risk avoidance and fragmented NOC governance also occur in Mexico.10 Strict procurement rules and budgetary oversight limit the autonomy of company managers, and frequent (though usually inconclusive) prosecutions against government employees by the Ministry of Public Administration—a body intended to fight corruption—make sure no one strays from the well-worn process. Moreover, Mexico’s oil sector is constitutionally off-limits to foreign players, even as its form of oil governance discourages company managers at NOC Pemex from taking any risks. Unwilling either to employ the foreign companies who are most skilled at risk management, or to allow the NOC to take on any risk itself, the country finds itself in a slow-motion crisis. Production from its most important field, Cantarell, progressively declines, while alternatives fail to materialize with sufficient speed. (At the time of this writing, Mexico’s two leading presidential candidates, apparently recognizing the seriousness of the situation, were signaling unprecedented openness to private investment in Mexico’s oil sector.11)

INCENTIVES FOR RISK-TAKING IN BRAZIL, NORWAY

Among countries with less immediate need to maximize hydrocarbon revenues than Angola, Nigeria or Mexico, a different approach to risk may emerge. The government may create incentives (deliberately or otherwise) that actively encourage the NOC to take risky actions by minimizing potential negative impacts on the company. Brazil’s NOC, Petrobras, was founded in 1953, before there was any significant, existing revenue stream in hydrocarbons for the government to protect.12 Norway’s NOC, Statoil, was established in 1972, not long after the first commercial discovery on the Norwegian Continental Shelf was made at Ekofisk in late 1969. At the outset, Norway was more concerned about minimizing any negative effects of hydrocarbon development on an already prosperous economy than on maximizing the financial benefits from oil.13

The Brazilian and Norwegian governments were notable for their reliance on less prescriptive, more monitoring-oriented strategies to control their respective NOCs. Both NOCs were afforded significant control over the revenues they generated and were largely protected from political intervention in operational decisions. Above and beyond the implicit cushions provided by their soft budget constraints and immunity from takeover and bankruptcy, both companies were granted substantial competitive advantages that further shifted risk to other players. In Brazil, risk was shifted onto the state (and its oil consumers) by granting Petrobras a monopoly over upstream and most downstream activities in oil that lasted from the NOC’s founding until the 1990s. Between 1974 and 1985, Statoil was given carried interests in exploration licenses that allowed it to shift all exploration risk onto the IOCs. The granting to Statoil in 1978 of a “golden block” that later turned into the Gullfaks field operatorship arguably increased risk to the Norwegian state, as did agreements that ceded operatorship of first Statfjord field, and later Troll field, from IOCs to Statoil after a predetermined length of time.

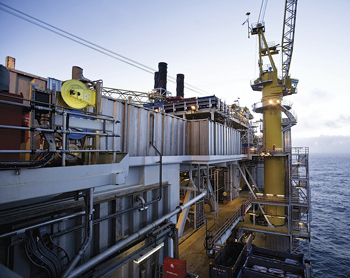

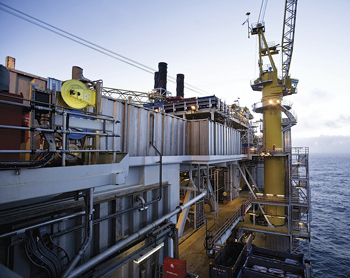

|

| Fig. 2. Statoil's Grane platform, offshore Bergen, Norway, in the Norwegian Sea, utilizes a wireless, self-organizing, mesh field network. |

|

These various provisions enabled both Statoil and Petrobras to pursue significant hydrocarbon exploration and development activities, and in so doing, to develop significant technological capabilities, with very little risk to themselves. Starting in the 1970s, Petrobras moved progressively deeper offshore, along the Brazilian continental shelf, to the point where, two decades later, it was one of the world’s leaders in technology for deepwater oil production. Statoil similarly played a leading role in developing technologies needed in its home territory, including undersea pipelines, subsea production systems and offshore platforms adapted for the harsh conditions of the North, Norwegian and Barents Seas.

The Statoil case highlights the double-edged nature of risk-taking. In interviews for our book, a senior Statoil executive described a company dictum that every project should have “at least five new things in it.” As a strategy for staying on the frontier of technology development, this is an ideal recipe. From the perspective of optimizing profitability, it may not always be. For example, Statoil had major problems several years ago with the launch of its Snøhvit LNG development in the Arctic, attributable, at least in part, to the use of a relatively untested LNG plant design. Two decades earlier, it suffered significant cost overruns when attempting a major retrofit of its Mongstad refinery, when it arguably could have gone with less risky options in Germany or Sweden. (Risk-taking is especially likely to backfire, when it is not backed by sufficient technical capability within an NOC. This was arguably the problem with a substantial exploration program in the 2000s by India’s ONGC, which produced a large number of dry holes.14)

On the other hand, companies like Petrobras and Statoil have been useful to their respective countries, precisely because they took on risky projects in the long-term national interest that IOCs—with their stricter commercial balancing of risk and reward—might not have. In the early days of Petrobras, IOCs with access to plenty of cheap resources elsewhere showed little interest in what looked to be expensive, scarce oil serving a relatively small domestic market. When the British government refused to accept natural gas from the Sleipner East field in 1985, Statoil served to buffer the impact on the Norwegian petroleum sector with a replacement project and ultimately offered a reliable landfall for Norwegian gas through development of the Statpipe gas pipeline from Statfjord to Kårstø.

Government investment through Statoil in long-term R&D helped not only to facilitate the development of hydrocarbons on the Norwegian Continental Shelf, but also to foster the development of an oil services industry in Norway that could then sell its high-value-added skills around the world. In this way too, Statoil’s pursuit of commercially risky activities ultimately provided a major long-term benefit to Norway’s economy through knowledge spillovers within the indigenous oil industry. China’s NOCs may be following a similar path with their heavy investments in R&D. The ultimate beneficiaries of these investments may be China’s oil service companies, which through the resulting technological learning may become increasingly capable of challenging international leaders like Schlumberger and Halliburton for contracts around the world.

In the past two decades, we have seen evidence of Petrobras and Statoil shifting from a strategy of risk-taking toward one of commercial risk management. It is no coincidence that this shift occurred as the two companies transitioned from being fully state-owned to partially private and more at arm’s length from government. The hallmark of a commercial approach to risk management is the deployment of various strategies to reduce uncertainty of outcome and limit capital exposed to loss. Such strategies include refinement of geological models (enabling bets to pay off more frequently), diversification across a global portfolio of opportunities, development of supply chain experience to more reliably link resources to end-use customers around the world, and application of engineering talent to reduce cost and thus capital exposure. Statoil is an example of an NOC that has come to use all of these commercial risk management strategies to a considerable extent. Any NOC could apply these “IOC-like” strategies in theory, but they tend not to evolve, naturally, until the NOC is exposed to direct competition for resources around the world, and few NOCs go abroad until they perceive resource scarcity at home, Fig. 3.

|

| Fig. 3. Percentage of 2008 working interest production (combined oil and gas) that is located in the home country for the 15 NOCs studied in Oil and Governance: State-owned Enterprises and the World Energy Supply. Data source: Wood Mackenzie.4 |

|

The transition over time from “risk taker” into “risk manager” does not come without drawbacks, however. During a research interview, an executive of a major Norwegian service company lamented how Statoil’s partial privatization in 2001 changed its approach to the risk of R&D. Whereas the old Statoil had housed R&D in a separate division and sponsored numerous technology initiatives that were a boon to the local services industry, the new Statoil located R&D within commercial business units like every other private oil major. In becoming a better risk manager—as, indeed, it had to do to serve the interests of its minority shareholders—Statoil was losing something of the risk-taking mentality that had helped boost development of the Norwegian services industry in its early phases.

CONCLUSIONS

As the discussion above suggests, each of these three different attitudes toward risk—risk management, risk-taking and risk avoidance—can have advantages. It can be useful for an NOC to avoid risk, if its government is highly dependent on oil revenue, but this approach usually means that it must allow IOCs to shoulder risks if the oil sector is to thrive. (Also important in this case is an effective tax system to appropriate a fair share of revenues from the IOCs.) Intelligent risk-taking by the NOC, on the other hand, can help build domestic technological capability, and may be a reasonable approach if the government has less need to maximize hydrocarbon revenue in the short term. (An important caveat, discussed at length in our book, is that using the NOC as a vehicle for developing broader technological capability is not easy and depends on a confluence of favorable circumstances.) Finally, commercial risk management by the NOC may be an appropriate model, where the company has developed some competitive advantages, and its government has few remaining expectations for the NOC apart from revenue generation. There is no right or wrong approach to risk for NOCs in a general sense. The goal of each government and its NOC should be to make sure that the way the firm takes, avoids or manages risk is of benefit to both the country and the NOC.

LITERATURE CITED

1. Victor, D.G., D.R. Hults and M.C. Thurber, editors, 2012. Oil and Governance: State-owned Enterprises and the World Energy Supply. Cambridge University Press.

2. Nolan P.A. and M.C. Thurber, 2012. “On the state’s choice of oil company: Risk management and the frontier of the petroleum industry.” Oil and Governance: State-owned Enterprises and the World Energy Supply. Cambridge University Press.

3. Hults, D.R., 2012. “Hybrid governance: State management of national oil companies.” Oil and Governance: State-owned Enterprises and the World Energy Supply. Cambridge University Press.

4. Wood Mackenzie, 2009a. Wood Mackenzie Corporate Analysis Tool. Wood Mackenzie website, accessed Oct. 11, 2009, www.woodmacresearch.com/cgi-bin/wmprod/portal/energy/productMicrosite.jsp?productOID=933381.

5. Wood Mackenzie, 2009b. Wood Mackenzie PathFinder Database (Nov. 2009 update). Wood Mackenzie website, accessed Jan. 18, 2010, www.woodmacresearch.com/cgi-bin/wmprod/portal/energy/productMicrosite.jsp?productOID=664098.

6. Heller P.R.P., 2012. “Angola’s Sonangol: Dexterous right hand of the state.” Oil and Governance: State-owned Enterprises and the World Energy Supply. Cambridge University Press.

7. Heller P.R.P. and V. Marcel, 2012. “Institutional design in low-capacity oil hotspots.” Revenue Watch Institute, New York, April 2012.

8. Thurber M.C., D.R. Hults and P.R.P. Heller, 2011. “Exporting the ‘Norwegian Model’: The effect of administrative design on oil sector performance.” Energy Policy 39(9).

9. Thurber, M.C., I.M. Emelife and P.R.P. Heller, 2012. “NNPC and Nigeria’s oil patronage ecosystem.” Oil and Governance: State-owned Enterprises and the World Energy Supply. Cambridge University Press.

10. Stojanovski, O., 2012. “Handcuffed: An assessment of Pemex’s performance and strategy.” Oil and Governance: State-owned Enterprises and the World Energy Supply. Cambridge University Press.

11. Rodriguez, C.M. and A.L. Caraveo, 2012. “Mexico oil opening first time since 1938 shows revival.” Bloomberg News, Apr. 26, 2012.

12. de Oliveira, A., 2012. “Brazil’s Petrobras: strategy and performance.” Oil and Governance: State-owned Enterprises and the World Energy Supply. Cambridge University Press.

13. Thurber, M.C. and B.T. Istad, 2012. “Norway’s evolving champion: Statoil and the politics of state enterprise.” Oil and Governance: State-owned Enterprises and the World Energy Supply. Cambridge University Press.

14. Rai, V., 2012. “Fading star: Explaining the evolution of India’s ONGC.” Oil and Governance: State-owned Enterprises and the World Energy Supply. Cambridge University Press.

|

AUTHORS

|

|

MARK C. THURBER is associate director at Stanford University Program on Energy and Sustainable Development (PESD). The program studies how policy and regulation intersect with business strategy, economics and technology to shape global patterns of energy production and use. Mr. Thurber holds a Ph.D. from Stanford University in mechanical engineering and a B.S.E from Princeton University in mechanical and aerospace engineering, with a certificate from the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. |

|

|

DAVID R. HULTS is a research affiliate at Stanford University Program on Energy and Sustainable Development (PESD). Mr. Hults received a J.D. from Stanford Law School in 2008 and has since worked for major law firms and a U.S. federal appeals court judge. Before coming to Stanford, he worked on Latin American economic issues at the U.S. Department of State. He previously earned a B.A. in international studies from the University of Florida and an M.A. in international relations from Yale University. |

|