Web Exclusive: Analysis of EPA's proposed clean air restrictions on oil and gas operations

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recently introduced a suite of rules regulating air emissions from oil and gas production—including hydraulically fractured wells. Once these rules are finalized, they may impose more stringent permitting and operating constraints.

|

RICHARD H. OSA, Stantec Consulting and TODD E. PALMER, Michael Best and Friedrich The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recently introduced a suite of rules regulating air emissions from oil and gas production—including hydraulically fractured wells. Once these rules are finalized, they may impose more stringent permitting and operating constraints.

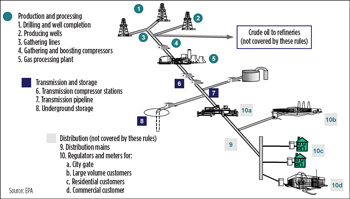

Critics have claimed that natural gas extracted from hydraulic fracturing has a greenhouse gas (GHG) production footprint comparable to that from coal combustion,1 and that the oil and gas production sector as a whole accounts for 40% of all methane emissions in the US. On July 28, 2011, the US EPA proposed its first comprehensive suite of Clean Air Act (CAA) rules to regulate air emissions from oil and gas production, gas-gathering and processing facilities, storage vessels and transmission pipelines2 (Fig. 1). The rules, as drafted, would impact over 1 million oil and gas producing wells, 3,000 processing plants and 1.5 million miles of pipeline. This article explains the legal framework EPA is using to support the proposed rules, provides a technical analysis of the emission limitations and discusses notable issues associated with the proposal.

BACKGROUND Since the 1970s, EPA has been regulating air emissions from oil and gas production using general CAA authorities that are not specifically tailored to the industry. For example, large oil and gas facilities-—i.e., those that potentially emit more than 250 tons per year (tpy) of a pollutant—that undergo construction or major modification are required to obtain pre-construction “new source review” permits, which contain stringent emission limitations. Historically, typical oil and gas production process units were considered too small to trigger these requirements. However, environmental groups have been aggressive in attempting to use this new source review program to regulate oil and gas production. Recently, EPA has suggested that a natural gas well and all non-contiguous gathering and compression equipment could be considered one large, single source of emissions for purposes of determining whether the combined processes were large enough to be subject to the new source review program.3 Like other industries, oil and gas facilities have also been prohibited from emitting pollutants at rates or concentrations that exceed EPA-defined national ambient air quality standards—ambient concentrations of a pollutant that are deemed protective of human health and the environment. States and local units of government are empowered to impose emission limits on facilities within their jurisdictions to protect these air quality standards. In 1985, EPA promulgated its first air emission regulations specifically targeting oil and gas production. The regulation was a New Source Performance Standard (NSPS) that narrowly focused on volatile organic compounds (VOC) and sulfur dioxide (SO2) emissions from newly constructed natural gas processing plants.4 Under the CAA, EPA is required to establish an NSPS for new, reconstructed and modified emission units in source categories, such as oil and gas production, that have been shown to cause or significantly contribute to air pollution.5 The EPA must establish NSPS requirements for these source categories that reflect the degree of emission reduction achievable through the application of the ‘‘best system of emission reduction’’ that has been demonstrated in practice. EPA may consider costs when establishing an NSPS. EPA is obligated to review each NSPS every eight years and revise as appropriate. EPA has not reviewed or revised the oil and gas sector NSPS since its original promulgation 25 years ago. In June 1999 and January 2007, EPA promulgated emission standards specifically for controlling hazardous air pollutants (HAPs) emitted by oil and natural gas production, and natural gas transmission systems.6 These so-called National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants (NESHAPs)7 are required to reflect the maximum degree of HAP emission reduction achievable as determined by EPA after a review of the best controlled similar sources. As with NSPS, EPA can consider compliance costs in establishing a NESHAP (but with important limitations), and EPA must review NESHAPs every eight years. EPA must also analyze the health and environmental risks that remain after a source category complies with its NESHAP, and revise the standard, if necessary, to address any residual risk. EPA has never completed a residual risk analysis for the oil and gas sector NESHAP. In January 2009, two environmental groups filed a lawsuit alleging that EPA had failed to perform its NSPS and NESHAP review obligations. In February 2010, EPA essentially conceded the point by agreeing to a consent decree committing EPA to propose new NSPS and NESHAP emission limitations for the oil and gas industry by July 28, 2011, or conclude that new standards are not necessary.8 EPA further committed to take final action on these proposed standards by Feb. 28, 2012. The EPA’s July 28, 2011, proposal is the first step in complying with the consent decree. Aside from proposing to simply lower the existing NSPS and NESHAP emission limits, the proposal would significantly expand the universe of emission sources and activities in the oil and gas production sector that would be subject to the emission limitations. PROPOSED RULES Beyond simply ratcheting down the existing NSPS and NESHAP limits, the rules would increase the number of source categories subject to control and, consequently, greatly increase the number of facilities potentially subject to air regulation. The NSPS rule explicitly identifies hydraulically fractured wells as “affected” operations. This alone would increase the number of affected facilities by an estimated 11,400 per year. NSPS. The current NSPS rules require VOC leak detection and repair (LDAR) for gas processing plants (Subpart KKK9) and technology-based SO2 emission limits for sweetening units and sulfur recovery units in processing plants (Subpart LLL10). The proposed NSPS rule would establish a new Subpart OOOO, to include the existing Subpart KKK and LLL requirements. The rule would additionally limit VOC emissions from well completion activities and specifically apply to fracturing and refracturing operations. Most hydraulically fractured wells would be subject to “green completion” or flaring under the new rule, to achieve a 95% VOC emission reduction and 90% collection of salable natural gas. Figure 2 illustrates one approach to green completion. Flaring would only be an option in situations not meeting criteria for green completion and where flaring does not pose a hazard.

Other emission sources the proposed rule would newly regulate include compressors, pneumatic controllers and storage tanks. The rule also proposes to strengthen the existing NSPS LDAR requirements applicable to processing plants. For instance, the proposed new rule would reduce the criterion for what constitutes a “leak” from a measured air concentration of 10,000 ppm down to 500 ppm VOC. Table 1 compares the key provisions of the current NSPS with those of the proposed new rule for production and processing, and transmission and storage operations.

The proposed NSPS rules would only apply to “newly constructed”, “reconstructed”, and “modified” emission sources within the source categories specified in the standard. By statute, the requirements are effective upon startup of sources on which construction commenced after promulgation of the proposed standard—in this case, after Aug. 23, 2011. The true cost of complying with the proposed rule is still quite uncertain. Some of the new requirements, such as the strengthened LDAR requirements, are known quantities. The lowered, 500 ppm VOC leak criterion has already been implemented in the Synthetic Organic Chemical Manufacturing NSPS (Subpart VV). However, the impact of the green completion provisions would most likely be expressed as a reduction in the number of economically viable developments—an outcome on which it is difficult to hang a price tag. It may well be that, for those projects that are implemented, the value of the recovered gas will offset the increased compliance cost. What such a valuation may overlook are the otherwise economical projects that are abandoned or never pursued, due to the net cost imposed by green completion requirements. In their preliminary comments, the American Petroleum Institute advised EPA that there are four conditions necessary to make green completions feasible and that, “If all of these conditions are met, then green completions may be a valid practice for a particular well. If any of these conditions cannot be overcome, then green completions cannot be used on a particular well.”11 NESHAP. The proposed rule would strengthen the current oil and gas production (Subpart HH12) and gas transmission and storage operations (Subpart HHH13) LDAR standard. The proposed rule would also establish emission limits for small dehydrators that are located at facilities characterized as “major” sources. Likewise, all crude oil and condensate tanks at “major” sources associated with oil and gas production would be regulated under the proposed rule. Despite arguments to the contrary from the American Petroleum Institute,14 EPA concluded that the current 1-tpy benzene compliance option available to “major” oil and gas production sources under the current NESHAP poses an unacceptable risk and, consequently, has proposed eliminating this alternative. Existing key provisions of NESHAP are compared with those of the new proposal in Table 2. Consistent with the NSPS, the previous LDAR requirements have been strengthened, reducing the “leak” criterion from 10,000 ppm to 500 ppm VOC. As noted previously, this criterion is identical to that applied to other industries. While the actual dehydrator emission limit has not changed, the proposed rule would apply it to certain smaller units that had been exempt under the existing NESHAP—a change that may add significant compliance cost, depending on site-specific conditions. Elimination of the 1-tpy benzene exemption level limits operators’ compliance options—with consequent increased cost.

ISSUES ARISING FROM PROPOSED RULES New air regulations sometimes have the unintended consequence of triggering costly and burdensome new source review permitting obligations. For example, activities undertaken to comply with a rule (e.g., installation of emission control technologies) can be considered a “physical or operational change” which, in turn, can constitute a “major modification” triggering new source review permitting requirements. EPA has attempted to allay such concerns by asserting that the proposed rules will generally result in emission decreases,15 or by simply stating that the rule will not trigger new source review permitting.16 Nonetheless, regulated sources should be very aware of this issue as they develop plans for compliance with the final rules. The proposed rules lack clarity as to the regulatory consequences stemming from a well workover. As mentioned, NSPS requirements generally apply to newly constructed or modified existing emission units. The term “modification” generally encompasses activities that result in an increase in the maximum emission rate of an emission unit. Well workovers will increase the production rate of a particular well, which in turn can result in an increase in the emission rate attributable to the well itself, as well as downstream transmission and storage units. The proposed rules lack clarity as to whether well workovers will be considered a modification triggering NSPS requirements, and if so, what are the regulatory obligations for interconnected, ancillary emission sources. Similarly, EPA contends that a completion associated with refracturing performed at an existing well (i.e., a well existing prior to Aug. 23, 2011) would be considered a “modification.” This would, in turn, trigger the obligation that the well meet the proposed NSPS emission limitations. EPA reasons that the refracturing would constitute a physical change to the existing well resulting in emission increases during the refracturing and completion operation. As mentioned, EPA must consider the cost of compliance when establishing NSPS and NESHAP emission rates. EPA’s general opinion has been that the proposed rules will actually reduce costs to the industry because the required controls will prevent leakage and loss of otherwise salable product. However, EPA’s analysis may not fully consider that many wells impacted by this regulation are already operating on a thin margin due to low production rates. The value of any product recovered by the controls may not justify the additional compliance costs. This could lead to the unintended consequence of disproportionately impacting smaller operations that cannot readily absorb these expenses and remain competitive. Another set of issues will revolve around the stringency of controls. Environmental groups have asserted that these NSPS standards should achieve at least a 90% reduction in methane emissions. These groups cite specific examples of technology that can achieve this level of control in practice, and emission programs at the state, county and international levels that already require this level of reduction. Although EPA’s proposed rules do require reductions in this range for some emission sources, that is not the case for all source categories. EPA has structured the proposed rule to ensure that sources newly subject to NSPS requirements as a result of this proposed rule will not be required to obtain a Title V operation permit, unless the source is otherwise required to obtain a Title V permit for other reasons. As a general rule, the CAA requires any source subject to an NSPS to obtain a Title V permit. However, EPA is authorized to exempt, by rule, NSPS sources from the requirement to obtain a Title V permit. The agency has proposed exempting well completions, pneumatic devices, compressors and/or storage vessels from the requirement to obtain a Title V permit solely as a result of sources being subject to one or more of the proposed NSPS requirements.17 This will reduce the Title V regulatory burden that would otherwise be imposed on these smaller sources and permitting authorities. In addition, by constituting a federally enforceable limitation on a facility’s potential to emit, the proposed NSPS would make it less likely that a facility would exceed the annual emissions values that would make it subject to Title V permitting. EPA has proposed that the NSPS and NESHAP limits be met at all times, including during periods of start-up and shutdown of equipment. For certain source categories, this is not technically or operationally feasible, in which case EPA has generally crafted emission limitations to exclude such events. EPA has specifically sought comment as to whether the oil and gas production sector believes it reasonable to require all regulated emission sources to meet the proposed standards during start-up and shutdown. Some have expressed concern with the ability of industry to install and implement the technology-based standards in the proposed rules in a timely manner. As mentioned, the rules will impact a large number of emissions sources, and there is a limited supply chain to supply the required control devices. Consequently, there have been requests to delay the effective date of the technology based standard for at least one year. CONCLUSION By the time this article is published, EPA will have closed the public comment period and will be evaluating what will likely be a significant volume of comments on the proposed NSPS and NESHAP rules. The agency has already held three public hearings on the proposal, which have generated significant comment from industry, states, environmental groups and the public. At this time, EPA is under a consent decree to take final action on the rule by Feb. 28, 2012. However, the litigants in that lawsuit have agreed to extend this deadline unitl April 3, 2012, which still must be approved by the court. It is possible that this deadline will slip, either due to EPA inaction or by mutual agreement of the litigants that filed the lawsuit in 2009. Past precedent suggests that it is virtually certain that these rules will be the subject to legal challenges that may take years to resolve. In any event, industry should closely analyze these rules, once they are finalized, and incorporate them into the individual company’s environmental management systems and CAA compliance plans. LITERATURE CITED

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Shale technology: Bayesian variable pressure decline-curve analysis for shale gas wells (March 2024)

- What's new in production (February 2024)

- Prices and governmental policies combine to stymie Canadian upstream growth (February 2024)

- U.S. operators reduce activity as crude prices plunge (February 2024)

- U.S. producing gas wells increase despite low prices (February 2024)

- U.S. drilling: More of the same expected (February 2024)