What's new in production

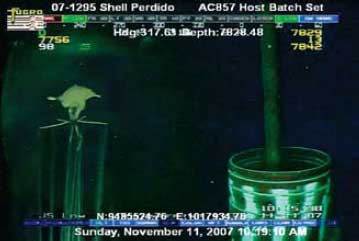

Spider-Squid and other deepwater discoveries The video circulated through the World Oil email directory in early August - a jerky ROV recording from November 2007 of an eerie creature with giant, slowly flapping fins and bizarre jointed tentacles that dangle far below. Dubbed “Spider-Squid” by World Oil staff, the creature floats placidly along the seafloor, unfazed by at least two ROVs as well as drilling at the nearby wellhead in what the video identifies as Shell’s Perdido development in the deepwater Gulf of Mexico. Speculation abounded: Had Shell discovered a new species? Was it, in fact, some sort of squid? Or spider? Or Martian? Three months later, National Geographic News answered our questions with an article identifying the Perdido visitor as a rarely seen Magnapinna squid (“Alien-like squid with ‘elbows’ filmed at drilling site,” Nov. 24, 2008). Named after its “big fin,” the squid was first identified in 1998. With its unique “elbowed” tentacles, the discovery was so unusual that biologists classed it in its own family, Magnapinnidae. A scientific report released in 2001 established that this type of squid occurs worldwide in the permanently dark zone below about 4,000 ft. Adults observed to date range in length from 5 to 23 ft. ROVs have filmed about a dozen Magnapinna squids. The National Geographic article highlights a side benefit of oil and gas development in deep water: opportunity for biologists to study - and perhaps discover - elusive deep-sea creatures. Exploration of these species’ habitat by ROVs or manned submersibles is often too time consuming and expensive for biologists, but oil industry ROVs are becoming increasingly familiar with the deep water as they accompany rigs and production platforms that spend months to years at a single location.

In fact, an estimated 95% of ROV activity is by the oil industry, making partnership with the industry very attractive for biologists. One such partnership is the UK-based SERPENT (Scientific and Environmental ROV Partnership using Existing iNdustrial Technology) project. SERPENT scientists train oil industry ROV operators to spot and take useful footage of strange deep-sea creatures, and visit partnering offshore installations regularly to obtain the data for analysis. These methods have resulted in several peer-reviewed scientific papers, available on SERPENT’s website. However, there are reasons to be wary of such partnerships, both for scientists and for industry. For biologists, reliance upon for-profit corporations for access to seafloor data may create conflicts of interest that taint their findings. However, the enormous resource the companies can provide is likely to far outweigh such concerns. Participating oil and service companies, on the other hand, have little to gain besides a PR boost, plus the minor advantage of having researchers cooperate, rather than compete, for deep-sea equipment. And they may put projects at risk by seeking out organisms that could conceivably be disrupted by their activity, according to Andrew Shepard, director of the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Undersea Research Center. For instance, the discovery in the 1980s of chemosynthetic animal communities near cold seeps in the GOM led the US Minerals Management Service to enact regulations that require companies to provide data to help MMS determine if chemosynthetic communities are present and, if so, may require the companies to relocate operations. “Now on the horizon are efforts to protect newly discovered deep coral communities,” Shepard said in an email interview. He added, “Neither of these communities is considered threatened or endangered by [Endangered Species Act] standards. However, they are rare and important enough for MMS to prohibit direct impacts of hydrocarbon activities.” SERPENT Project Coordinator Dr. Daniel Jones said such cases shouldn’t deter companies. Discovery of a new species at a drilling site would not confer any protection on the species, he said in an email interview, since such protection is defined by statutes and regulations that arise from study of impacts on known species. Furthermore, he says, “If there is a species that is already protected in the area being developed - e.g., the cold-water coral Lophelia pertusa - then environmental surveys done prior to drilling by a survey company should find this.” Thus, by the time the company is collecting data for the research organization, any protected species should be already identified. Of course, there is always the possibility that preliminary surveys will miss a protected species that will then be seen by an operator’s ROV and require implementation of costly avoidance strategies. Or a species newly discovered at a drilling site could later earn protected status and be proven to be disturbed by the operator’s activity there, just as production is ramping up or a workover is needed. Perhaps creative contract negotiations for such industry-academic research partnerships, recognizing the great service participating companies perform for the public, will find ways to protect company investments from these and other eventualities. Until then, please approach the Spider-Squid with caution!

|

|||||||||||

- What's new in production (February 2024)

- Prices and governmental policies combine to stymie Canadian upstream growth (February 2024)

- U.S. operators reduce activity as crude prices plunge (February 2024)

- U.S. producing gas wells increase despite low prices (February 2024)

- U.S. drilling: More of the same expected (February 2024)

- U.S. oil and natural gas production hits record highs (February 2024)

- Applying ultra-deep LWD resistivity technology successfully in a SAGD operation (May 2019)

- Adoption of wireless intelligent completions advances (May 2019)

- Majors double down as takeaway crunch eases (April 2019)

- What’s new in well logging and formation evaluation (April 2019)

- Qualification of a 20,000-psi subsea BOP: A collaborative approach (February 2019)

- ConocoPhillips’ Greg Leveille sees rapid trajectory of technical advancement continuing (February 2019)