What's new in exploration

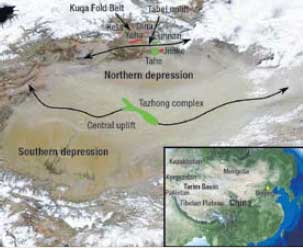

50 years of exploration in the Tarim Basin It has been 50 years since the first oil and gas discovery was made, yet much of China’s Tarim Basin is still a petroleum frontier. Fewer than 1,000 exploration wells have been drilled despite the discovery of seven fields each with recoverable reserves of 500−3,000 million boe. The great size and remoteness of the basin contribute to its under-exploration. It covers 216,000 sq mi, or about 80% of the area of Texas, and is located almost 2,000 mi from Beijing in extreme western China bordering Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan (see figure). The main reason for limited drilling, however, is that exploration has not been opened for international participation except during limited periods of time and under restrictive operating agreements. The Tarim Basin has a world-class petroleum system with a resource potential of 78 billion bbl of oil and 296 Tcfg. Every interval from Cambrian to Holocene is charged except Devonian and Triassic. Rich source rocks are found within Cambrian, Ordovician, Permian, Jurassic and Triassic strata, and seven active petroleum sub-systems have been identified. Ordovician carbonate, Carboniferous clastic, and Cretaceous and Tertiary clastic reservoirs are the chief producing intervals. Most oil fields are concentrated in the northern part of the basin on the Tabei uplift and in the Kuqa fold belt (pronounced “koo-cha”), though the super-giant Tazhong Field Complex is located on the Central uplift.

The tectonic and stratigraphic evolution of the basin was complex. In the early Paleozoic epoch, the Tarim Block was probably separate from Pangaea. As much as 10,000 ft of mostly shallow marine and coastal plain strata accumulated during the Cambrian and Ordovician. Ordovician platform carbonates and dolomitized shallow water successions comprise the most important petroleum reservoirs today. Late Ordovician uplift resulted in widespread exposure of the platform. Deep erosional valleys and canyons formed, with as much as 6,000 ft of relief, and were later filled with clastic sequences. Karsting, erosion and subsequent fill produced classic buried hill and complex stratigraphic traps that account for most of the petroleum accumulations in the basin in combination structural-stratigraphic traps. Platform carbonate deposition in the Carboniferous was interrupted during the Late Paleozoic Orogeny when the Tarim Block and Tian Shan Block to the north converged. Marine sequences were uplifted, and deep paleosols formed across the basin. Eolian and shallow marine tidal and shoreface sands of the Donghe Sandstone were deposited. The Donghe Sandstone is the other important Paleozoic reservoir in the Tarim. During the Triassic and Cretaceous periods, convergence from both north and south resulted in foredeeps (northern and southern depressions) on both margins of the basin separated by a broad flexural arch (Central uplift). These foreland basins were dominated by nonmarine clastics shed off the adjacent highlands. The middle Tertiary collision of India and Eurasia produced compression and strike-slip faulting that formed many of the structural traps in the Kuqa fold belt, and on the Tabei and Central uplifts. Continental deposits continued to dominate the basin fill, and reservoir intervals at Dina, Kela and Dabei Fields in the Kuqa fold belt consist of both Cretaceous and Tertiary nonmarine sandstones. About 8.5 billion bbl of oil and 30 Tcf of gas have been produced to date, and the five largest fields have been discovered in the last 10 years. Regional seismic data was first acquired in 1983. Many discoveries were made in Ordovician carbonate and Carboniferous clastic reservoirs, including the Tazhong (1,465 MMboe, 1989) and Tahe (3,300 MMboe, 1998). More recent exploration in the Kuqa fold belt resulted in gas discoveries at Dina (2,474 MMboe, 2001) Kela (1,564 MMboe, 2004) and Dabei (813 MMboe, 2007). The 2,600-mi West-to-East Pipeline now carries Kuqa gas to Shanghai on the east coast of China. I have worked on projects in the Tarim Basin since 2005, and visited the basin most recently this May. I have great respect for the strong technical approach that PetroChina and Sinopec employ as they continue to explore Tarim. In addition to using all available seismic and subsurface technology, their E&P teams are involved in rigorous programs of field geology and core interpretation. Two companies, however, cannot effectively evaluate and explore a basin as large and geologically complex as the Tarim. Beginning in 1993, licensing rounds were held and several international companies evaluated tracts in the basin. While work programs were executed by foreign companies, offered tracts had low exploration potential, and licensing agreements were restrictive. After a few years, most companies exited. Again in 2006, a licensing offer was announced, and several international companies purchased data packages, but bid rounds never occurred. Competition is critical to ensure the efficient development of petroleum resources, and Tarim is no exception. Vast areas are only slightly deformed, and stratigraphic emphasis will be critical. The number of seismic and drilling programs must be greatly expanded to meet China’s need for oil and gas. I do not understand why China doesn’t encourage more aggressive exploration and development in its own highest-potential basin by inviting competition from foreign companies. IHS provided data about Tarim Basin plays, petroleum system, and exploration history. IHS’s ongoing support of this column is greatly appreciated.

|

||||||||