What's new in exploration

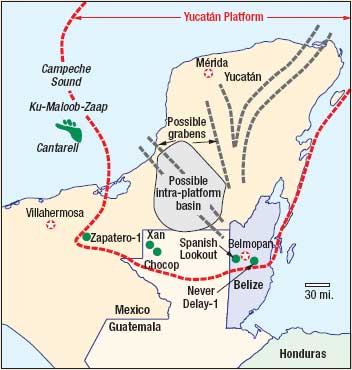

Another discovery in Belize A second light-oil discovery in Belize confirms that a commercially viable petroleum system exists on the Yucatán Platform. It may also have important implications for Mexico’s underexplored Yucatán Peninsula. In December 2007, Belize Natural Energy Ltd. (BNE) tested oil from several Cretaceous carbonate reservoirs in its Never Delay-1 (ND-1) well east of Belmopan, see figure. While few details are available, BNE says that it is a “substantial discovery.” The ND-1 well tested light, sweet oil from the same Albian-Turonian Yalbec Formation reservoirs that produce at the company’s Spanish Lookout Field discovered in July 2005 in the same license area. The heavy oil produced in Guatemala at the Xan and Chocop Fields was probably generated from immature local source rocks. The light oil at Spanish Lookout and ND-1 probably migrated from the Mexican part of the Yucatán Platform to the north, where there was sufficient burial depth to generate mature oil. The Yucatán Platform includes the Yucatán Peninsula and Marine Shelf in Mexico, and the northern part of Belize and Guatemala. Major oil production is found immediately west of the Yucatán Platform in Campeche Sound, Macuspana Basin and Reforma Trend areas of Mexico. This production includes the super-giant, Cantarell (18 Bbbl), and Ku-Maloob-Zaap (5 Bbbl) oilfield complexes.

Before the Spanish Lookout discovery, there was no petroleum production in Belize. Fifty wells were drilled from 1956 to 1997 and many had shows of oil and gas. In 2002, BNE acquired a 463,000-acre exploration license, and negotiated a Production-Sharing Agreement the next year with the government of Belize. BNE reprocessed 267 mi of existing 2D seismic data in the license area, and subsequently acquired more than 1,500 mi of new data in 2004–2005. The company used an impressive technology workflow to interpret and integrate the seismic data using surface and subsurface geology, geochemistry, reprocessed gravity and magnetic data, and space-shuttle imagery to identify four prospect areas. Two of those prospects resulted in the Spanish Lookout and Never Delay discoveries. EUR for the former is 10 million bbl of oil (IHS). The first commercial oil on the Yucatán Platform was discovered in Guatemala. Xan Field (81 million Bbbl EUR) was discovered in 1981, and the Chocop Field (80 million Bbbl) in 1989. The light (38–39°API) oil found in Belize contrasts with the heavy (14–17°API) oil in Guatemala, as well as the 20–35°API oils produced in Campeche Sound. The Jurassic (Tithonian) source rocks in Campeche do not extend onto the Yucatán Platform, so at least two distinct petroleum sources can now be identified there. In Guatemala, probable source rocks are found in Cretaceous shale of the Coban Formation. The low-gravity oil in Guatemala results from immature source rocks, because the oil is not biodegraded or water-washed (IHS). A local source for the oil at Xan and Chocop is consistent with the geochemistry and maturity of Coban source rocks in the vicinity of those fields. It is possible that oil in Belize comes from similar source rocks, though its geochemical character has biomarker affinities to Jurassic oil. In either case, the greater thermal maturity of oil in Belize suggests that it must have been generated in the more deeply buried part of the Yucatán Platform to the north. State monopoly Pemex has assigned little petroleum potential to the peninsula based on the apparent absence of both a viable petroleum system and obvious structural traps. Pemex drilled 16 dry holes there during the 1950s through 1970s. Although non-commercial oil was found in the Zapatero-1 well (50,000 bbl EUR) in the southwestern part of the peninsula, no wells have been drilled since then, and no modern seismic data has been acquired. The Yucatán Platform is a geologically complex province that is covered by a deceptively simple carbonate platform (Rosenfeld, 2003). It is a rifted micro-plate that separated from South America soon after the initial opening of the Gulf of Mexico in Early Triassic to Middle Jurassic time. The Yucatán basement is extended, and linear gravity anomalies indicate that crustal stretching produced a series of horsts and grabens, see figure. It is likely that organic-rich source beds accumulated in graben areas as they did elsewhere along the rifted Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico margins. A broad negative gravity anomaly may represent an intra-platform petroleum source basin rimmed by carbonate buildups or banks (Rosenfeld, 2003). Since Late Jurassic time, as much as 20,000 ft of carbonates and evaporites accumulated over the peninsula. Although Mexico is among the world’s top oil-producing nations, few significant new-field wildcat discoveries have been made since 1982.* Production has fallen 12% since 2004, and the country will soon stop exporting oil unless new reserves are found. This will have serious implications for the US because Mexico is one of its main sources of imported oil. The effect on Mexico will be disastrous, since oil production now accounts for 37% of the country’s annual income. Pemex is perhaps the best example of how national oil companies can fail despite having abundant undiscovered petroleum resources. President Felipe Calderón is desperately trying to modify Pemex’s contractual structure to allow foreign E&P companies to work with Pemex to find new resources. He and most thoughtful Mexicans know that competition is the answer to Mexico’s petroleum problem. But the petroleum question is exceedingly delicate, complicated, and so deeply embedded in Mexican national pride that the date of expropriation of foreign oil holdings in 1938 is a national holiday. More importantly, the way that contracts are now awarded by Pemex benefits the ruling and wealthy elites, the same groups that Calderón must persuade to enact reforms that would hurt them. His efforts to change Pemex will fail. Even if his reforms were successful, it is unlikely that major foreign oil companies would consider investment arrangements that stopped short of the petroleum ownership that is prevented by Mexican law. All of my instincts and experience from working in Mexico’s energy sector tell me that nothing will change until the immigration safety valve to the US and its consequent flow of cash back to Mexico are ended. Only this, along with declining oil revenues, will create sufficient pressure on special interest groups to agree to change. At the same time, I sometimes entertain a harmless fantasy that at least the Yucatán Peninsula could be opened to some form of competitive exploration. Yucatán has no production, so nothing would be given away, and Pemex holds it in low exploration esteem. I doubt that major oil companies would be interested in exploring there for Belize-sized fields, but the kind of small companies, with access to capital and technology that are currently active in Belize, might find the Mexican part of the Yucatán Platform attractive for exploration. A weak precedent for increased foreign participation has been set with the multiple service contract model used in the Burgos Basin. Perhaps an expanded and liberalized version of that concept might get some traction in Yucatán. It’s just a fantasy, but an excellent one. * Nehring’s 1991 definition of a significant field in the Gulf of Mexico is greater than 50 million boe. Sihil (1,164 Bboe EUR found in 1998) is not a new-field wildcat but a deeper pool discovery to Cantarell, discovered in 1977. Zaap (638 MMboe EUR found in 1992) is not a new-field wildcat but a satellite to Maloob, discovered in 1979. The recently announced deepwater Lalail Field may be an important gas discovery but several recent offshore finds announced as giant fields by Pemex were later found to be much smaller after appraisal drilling and testing (e.g., Lankahuasa and Noxal). The 2007 Kuil and Xulum oil discoveries are notable but not significant since early estimates are less than 50 million boe together. IHS provided substantial information about the Yucatán Platform petroleum system and exploration history, as well as current production data and scouting information. IHS’s ongoing support of this column is greatly appreciated. BIBLIOGRAPHY Nehring, R., 1991, Oil and gas resources, in A. Salvador, ed., The Geology of North America, v. J, The Gulf of Mexico Basin: The Geological Society of America, p. 445–494. Rosenfeld, J. H., 2003, Economic Potential of the Yucatan Block of Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize, in C. Bartolini, R. T. Buffler, and J. Blickwede, eds., The Circum-Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean: Hydrocarbon habitats, basin formation, and plate tectonics: AAPG Memoir 79, p. 340–348.

|

|||||||||||

- Prices and governmental policies combine to stymie Canadian upstream growth (February 2024)

- U.S. producing gas wells increase despite low prices (February 2024)

- U.S. drilling: More of the same expected (February 2024)

- U.S. oil and natural gas production hits record highs (February 2024)

- Quantum computing and subsurface prediction (January 2024)

- U.S. upstream muddles along, with an eye toward 2024 (September 2023)

- Applying ultra-deep LWD resistivity technology successfully in a SAGD operation (May 2019)

- Adoption of wireless intelligent completions advances (May 2019)

- Majors double down as takeaway crunch eases (April 2019)

- What’s new in well logging and formation evaluation (April 2019)

- Qualification of a 20,000-psi subsea BOP: A collaborative approach (February 2019)

- ConocoPhillips’ Greg Leveille sees rapid trajectory of technical advancement continuing (February 2019)