|

Vol. 227 No. 1 |

| |

|

Business-risk management: An essential tool

On technically complex deepwater projects that require large sums of capital expended over long periods of time, there is no substitute for closely monitoring costs, assessing financial risks and implementing mitigation plans based on robust decision intelligence.

Richard Yale, JP Kenny, Inc., Houston, and Jan Ingar Knudsen, Norsk Hydro ASA, Houston

As operators continue to move into ever-deeper waters, the business risks associated with costs and safety increase exponentially. Oil and gas companies know that safety, cost, schedules, constructability and operability are the essential performance characteristics in executing successful deepwater projects. However, the business and technical strategies of these projects are not always optimally aligned. Too often there is a lack of communication between commercial asset managers, geologists, geophysicists, drillers, engineering and installation contractors, supply chain managers and, ultimately, those who will be tasked with operating and maintaining the deepwater facility once completed.

The causes for this disconnect are diverse. Some owner companies manage from commercial and technical silos, functioning only with their own objectives. Others, particularly smaller independents, may have little or no project infrastructure available, farming out small pockets of work to specialist companies and hoping that the technical solutions available will eventually support their business visions and economic investments. Many solutions have been investigated.

PAST POLICIES AND PROCEDURES

During the 1990s, there was an industry passion for mega-EPIC contracts, where the owner’s financial and technical risk could be re-assigned to a single contracting entity under the assumption that, by pre-investing risk monies, the out-turn costs of projects were clearly established. The perceived benefits seemed indisputable – a single contractor, minimum interfaces and a clear definition of the cost of the work.

Unfortunately, the reality often proved contrary to the expectations of either party in the agreement. Contractors were forced to manage multiple sub-contracts, most of which fell outside of their core business and portfolio of competencies. The prime contractors often faced change orders with variations from their sub-contractors for changes in scope that they believed were beyond their control. They passed them straight to the owner.

The owners considered that the variations should have been covered by their pre-investment in risk money and rejected the requests for additional monies, resulting in acrimonious project environments. Owners grumbled that the overruns in capital costs adversely affected their project economics. Simultaneously, contractors and sub-contractors claimed substantial losses from rejected change orders due to variations and badly defined scopes.

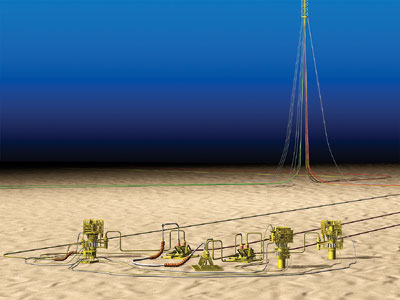

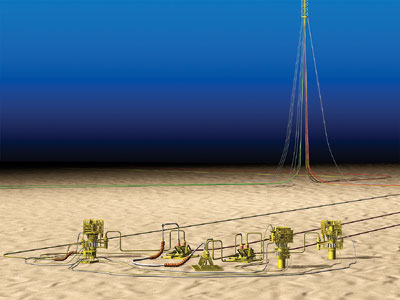

The real question is whether some of these acrimonious relationships between owners and contractors can be avoided with better business-risk management planning. JP Kenny, Inc. (JPK), a Houston-based project management company, and Norsk Hydro ASA (Hydro) are employing a suite of business-risk management tools developed by JPK to assist in the strategic planning of a Gulf of Mexico (GOM) deepwater subsea tieback project, Fig. 1.

|

Fig. 1. A GOM subsea tieback project.

|

|

Fig. 2 illustrates the decreasing influence on project expenditure over time. The depiction is not to scale and, in the current marketplace, where manufacturing facilities are full and installation hardware is at a premium, the early influence of strategic planning is even more acute.

|

Fig. 2. The influence of strategic planning on project expenditures decreases over time, highlighting the importance of comprehensive planning early in the lifecycle of a project.

|

|

BUILDING A FOUNDATION

The foundation to business-risk management of project planning resides in the facilitation of three fundamental workshops: 1) Contracting Strategy; 2) Political, Economic, Social and Technological (PEST) Assessment; and 3) Project Execution Planning.

These workshops are designed to ensure that, before any personnel-hours are wastefully expended, the commercial and technical objectives of the stakeholders have been explored and a common understanding of the project’s opportunities and challenges established.

The Contracting Strategy Workshop is designed to investigate the most efficient and cost-effective manner in which the project can be commercially executed. The spectrum of contracting strategies is examined, ranging from a turnkey approach to the award of multiple contracts and purchase orders. The results of the workshop are key to the role that the owner’s engineer will play. In the event that the selected strategy is to pursue a large EPIC contract based on a specific piece of technology or hardware, the owner’s engineer will act primarily as an interface manager tasked with commercial oversight to ensure the project acquires a fit-for-purpose product as described in the contractual documents.

Should the workshop conclude with the discovery that the project would be better served by awarding a series of smaller contracts, the role of the owner’s engineer will increase from merely specifying functionality to taking responsibility for ensuring that all of project components work together when integrated into the final product.

This initial workshop also offers a forum for the project team to decide on the appropriate Terms and Conditions that will be used for each contract or purchasing package that will be awarded.

The PEST Assessment Workshop is designed to evaluate the holistic risks the project might encounter during development and execution that may not be easily expressed in quantitative terms of cost or schedule. As the industry is forced to explore more diverse regions of the planet to find new sources of oil and gas, it is faced with more complex challenges. The PEST Assessment explores, among other considerations, the challenges of operating in new geographical locations, the expectations of the government and people of the host nation, quality of local infrastructure, environmental and social conditions, legal structures, and political stability in the surrounding regions.

The output of this workshop is a series of Boston matrices that rank the PEST risks in terms of probability of occurrence, severity of impact and the ability of the project team to mitigate the risk. These matrices are then converted into a Risk Mitigation Plan, including assignment of ownership for the risk, and will be carried through and developed throughout the lifecycle of the project.

The third workshop, the Project Execution Plan, is fundamental to the effective management of any project. The document resulting from this workshop will act as the roadmap for all project participants. It is designed to concisely define the projects description, objectives and drivers, give guidelines for communications and interface plans, and describe the project in terms of safety, cost, schedule, constructability and operability. The Project Execution Plan identifies the appropriate detailed plans and procedures that will be used by the development team during the definition and execution phases of the project.

Early execution of these workshops is extremely cost-effective and time-efficient. The workshops involve all commercial and technical stakeholders in the early decision-making processes that will steer the project through its evolution and increase the probability of long-term success. Depending on the scale of the project, each individual workshop generally runs from between one-half to a full day.

NEXT STEPS

Fig. 3 illustrates the missions, objectives and goals for project planning, execution and operation. Once the project’s commercial and technical objectives have been defined as accurately as possible, stakeholders are well-equipped to embark on evaluating the technical solutions available to the project and generate detailed cost estimates for any concepts being screened.

|

Fig. 3. A business-risk management process forces constant re-examination and increases accuracy.

|

|

The baseline cost estimates will take into account the findings of the workshops in terms of general economy of the host country, project supervision, labor conditions, site conditions, ease of operations, market conditions, equipment availability, and weather and other environmental conditions. Once a comprehensive, baseline, deterministic cost estimate has been established, a probabilistic Risk Analysis is performed to calculate the appropriate contingency that should be added to the base estimate to account for “known unknowns” and other uncertainties.

Cynics may argue that the use of Risk Analysis merely changes a wild guess to a scientific wild guess. This argument is inherently incorrect. The business-risk management process for cost estimating forces participants to constantly re-examine the estimate. Re-examination ultimately increases the validity of the stated level of accuracy. Fig. 4 shows the output of a Cost Risk Analysis performed on a mid-size subsea tieback project in the GOM.

|

Fig. 4. Example of a pre-FEED cost risk analysis performed on a GOM deepwater subsea tieback project (excludes costs of drilling and completion).

|

|

Equally important and often overlooked in the strategic planning phases of a project is Schedule Risk Analysis. Conventional critical path analysis techniques provide a robust and proven manner for quickly identifying the most likely critical path for the project. However, using a risk-identification process, based on the results of the workshops discussed earlier, the team will often reveal secondary and tertiary critical paths that may not at first have seemed obvious. Once again, it is not the statistical cleverness that is important; it is the introduction of a process that forces the team to review the project’s opportunities and challenges on a formalized basis, thus increasing their likelihood of success.

Using these initial workshops and processes will help the project clearly establish and document its goals and drivers and align the stakeholders’ strategic objectives. However, it is imperative that the results of these initiatives are not allowed to lie dormant or become perceived as an unnecessary imposition on the project participants.

ANATOMY OF BUSINESS-RISK MANAGEMENT

A well-conceived business-risk management plan should be structured to offer the project members an internally cohesive and externally coherent process for collecting, analyzing and distributing critical decision intelligence at all levels. Fig. 5 illustrates the structure of the JPK Business-Risk Management Toolkit.

|

Fig. 5. The anatomy of JPK’s business-risk management toolkit.

|

|

The business-risk management plan should encompass every aspect of managing a project. This includes management and analysis of costs in terms of commitments, liabilities and cash flow, as well as meaningful methods of collecting and reporting progress and measuring schedule performance. In addition, such a plan must address management of the procurement process, including vendor inspection, desk and field expediting, and purchase order management. Most importantly, the plan must have a robust system for the management of contracts.

CONTRACTS MANAGEMENT

With millions and sometimes hundreds of millions of dollars at stake, clarity of the contracting arrangements is paramount. The process starts with the preparation of Request for Proposal (RFP) packages. This process is a prime example of the necessity for alignment of business and technical objectives. Too often, engineering companies are asked to prepare scopes of work, specifications and data sheets and send them to the commercial department who will then insert them as written into an RFP package. This practice is an example of the misalignment of business and technical objectives, and generally results in poor quality tender packages being presented for contractors to quote against. Later, this leads to the acrimonious relationships discussed earlier.

A well-crafted RFP package will be the result of collaboration of the commercial, technical, quality and HSE groups. A table of contents should be drawn up and the preparation of the relevant appendices assigned to an owner. It is important that the authors understand that the appendices, including the scope of work and the specifications, contain no contractual language whatsoever.

Scope of work. The scope of work should be written to clearly define the services for which the owner company wishes to contract. It should not contain the specifics of how the work is to be done; these instructions are contained in the specifications. A well-written scope of work will allow the commercial department to prepare compensation sheets that can be clearly cross-referenced back to the scope document.

It is good practice to split the scope of work into a section containing a general description of the services, followed by a series of work packages that concisely describe the precise services required. Each work package may have several sub-sections, each of which should be carried across to the pricing sheets, so there is no ambiguity between the parties regarding the pricing of individual line items.

Pro-formas. In today’s electronic age it is easy to send out pro-formas for completion by the potential contractors. By making completion of the pro-formas a conditional precedent of bid acceptance, the owner company increases its likelihood of receiving bids that can be evaluated on an equal basis.

Terms and conditions. Selection of the appropriate terms and conditions is of primary importance. It is a mistake to make the terms either too general or too onerous. A well-written contract is fair and equitable to both parties, clearly delineating the extent of both parties’ responsibilities and the limits of their liabilities. Periods of warranty, levels of insurances to be carried by each party, and the terms of liquidated damages should be clearly stated. The definition of Force Majeure should be carefully written to avoid potential disputes. Where marine activity is included in the services being contracted, responsibility for offshore environmental and climatic conditions and mechanical downtime must be addressed.

Review. Once the scope, specifications, compensation sections, terms and conditions, etc. have been prepared, the RFP package should be reviewed as a complete package. Ultimately, the RFP documents will be converted into a single contract document, so it is important that there are no discrepancies between the documents contained in the various appendices that can later give rise to claims.

Well-crafted contractual documents, where both parties clearly understand the division of risk and feel adequately protected, will significantly enhance the probability of the contract being executed within the time and cost parameters agreed.

Contract administration. Contracts management doesn’t end after the bidding process and contract signing. The business-risk management plan must include for the ongoing administration of the contract.

Of course, it would be naïve to suggest that even the best written contract documents can completely protect either party. From time to time, disputes will occur. Maintenance of all documentation including transmittal of documents and drawings, communications of a technical or commercial nature, and the daily field reports compiled by the site representatives allow claims to be fairly evaluated against the original terms of the agreement. Poor record keeping by either party can result in either claims being paid by owner that may have been disputed or, conversely, valid contractors’ claims being rejected due to poor documentation and support.

The importance of the contract in the relationship between the owner company and contractor cannot be overstated. The cost of administrating a contract properly is negligible in comparison with the potential savings to the project’s bottom line.

EXECUTIVE REPORTING

With robust cost, schedule, procurement and contracts management tools in place, the final element of a well-conceived business-risk management plan is Executive Reporting. The data collected from all the project groups needs to be compiled into a concise report that allows project managers, directors, partners, investors and other interested parties to understand the project status in both commercial and technical terms, the outstanding risks and existing mitigation plans, the forecast final cost at completion, and the most likely date for project completion.

The Business-Risk Management Toolkit employed by Hydro includes a reporting structure designed to be presented as 30 slides, each taking about one minute to present. This allows an hour-long monthly meeting to be efficiently split between presentation time and a period for discussion.

As operators move into deeper waters, they have discovered that properly designed and implemented business-risk management tools and processes will assist them in achieving the ultimate goal of constructing safe and efficient facilities at an improved rate of return on capital invested.

THE AUTHORS

|

|

Richard Yale is business risk manager for JP Kenny, Inc., a Houston based project management company. Richard has over 25 years project management experience in the international oil and gas Industry. He has specialized in all aspects of business-risk management including: field development economics; contract strategy development; contract preparation; negotiation and administration; procurement management; capital cost estimating; cost and schedule management; and probabilistic cost and schedule risk analysis.

|

|

|

Jan Ingar Knudsen has over 30-year’s experience on pipeline, marine operations and subsea development projects, several as project manager. Presently he holds the position as subsea manager for Norsk Hydro’s first development in the Gulf of Mexico – Telemark field development, in 4,400 ft of water.

|

| |

|

|