Supply and Demand

Recent gas market changes parallel US need for more LNG

Gas demand considerations virtually mandate an escalation in LNG usage by the US. Yet, a build-up in LNG infrastructure has its own problems, and US policymakers must keep a careful watch on the effect this may have on traditional gas production.

Saeid Mokhatab, EMERTEC Research and Development Ltd., Halifax, Nova Scotia; William A. Poe, Consultant, Houston; and Michael J. Economides, University of Houston, Houston

Total US natural gas demand in 2006 is projected to remain near 2005 levels, and then increase by 2.3% in 2007. Residential demand, in particular, is projected to slip somewhat during 2006 from 2005 levels, and then increase 3.3% in 2007. Natural gas demand for generating electricity is expected to fall 2.1% in 2006 because of the warm January, and the assumed return to normal summer weather, then increase 2.2% in 2007.

However, strong growth in natural gas-intensive industrial output is expected both this year (3.1%) and next year (2.2%). Domestic dry gas output in 2005 is estimated to have declined 2.7%, owing mainly to hurricane-induced infrastructure disruptions in the Gulf of Mexico. Dry gas production is projected to increase 3.0% in 2006 and 1.3% in 2007 (US Energy Information Administration, Short-Term Energy Outlook, 2006).

OVERVIEW

Transportation is an essential aspect of the gas business, since gas reserves are often quite distant from their main markets. Gas is far more cumbersome than oil to transport and most of it is transported by pipelines. There is a relatively well developed network in the Former Soviet Union, Europe and North America.

However, in its gaseous state, natural gas is quite bulky – a high-pressure pipeline can transmit only about one-fifth of the amount of energy, per day that can be transmitted in an oil pipeline, even though gas travels much faster. When gas is cooled to – 160°C, it becomes liquid and much more compact, occupying 1/600 of its gaseous volume. Where long overseas distances are involved, transporting gas in its liquid state becomes economical. The liquefied natural gas (LNG) industry is set for a large, sustained expansion, as improved technology has reduced the cost of transporting formerly stranded gas reserves in liquid form. This shift in gas market dynamics will further commoditize natural gas globally.

LNG has received considerable attention in recent years. Most of this increased attention has resulted from realization that domestic production is declining. It has been augmented by former US Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan’s testimony that increased LNG imports will be needed to stave off a gas shortage in the US. While it is true that LNG imports are likely to increase 500% over the next few years, they are currently so small that even a five-fold increase will only have a small impact on the imbalances that exist in the North American gas market.

The US has the world’s largest number of LNG facilities, including 113 LNG storage and peak shaving facilities out of 200 in existence worldwide. The largest concentration of LNG storage facilities is in New England, where they number 40. Why then, does the US only have four of the world’s 40 LNG import terminals?

The need to transport gas long distances across oceans led to development of international LNG trade. LNG as a tradeable commodity is emerging into a fully-fledged financial complex, and it will add to that complex by providing a physical arbitrage between different regional markets. While neither a political nor an environmental panacea, LNG offers a global commodity that can meet the growth in demand for natural gas.

The combination of secure energy supplies, higher gas prices, lower LNG production costs, rising gas import demand (with an increasing demand for clean energy in the developed and developing world), and the desire of producers to monetize their gas reserves, is setting the stage for increased LNG trade in the years ahead. LNG trade represents 6% of worldwide gas consumption, but only about 1% of US consumption. US gas consumption represents just over 26% of total worldwide gas consumption.

US SUPPLY AND DEMAND

The US market has a large number of buyers and sellers, both major producers and independents. For many years, prices were kept at artificially low levels by regulation. There was also an interesting split between intrastate and interstate markets, where gas held for sale within the producing state could be sold for higher prices than the “allowed” price for sales in interstate commerce.

While demand for gas continued to increase through the 1960s and 1970s, supply did not seem to keep pace. By the mid-1970s, there was already concern that the US would experience severe shortages of natural gas. In response, a number of companies proposed LNG import terminals to address market supply requirements. At that same time, gas prices were regulated at the wellhead, and removing regulation was seen as an incentive for producers to increase exploration and development, and bring new gas supplies to the market.

The demand for natural gas in the US was boosted during the 1980s, in part by the desire to diversify energy resources in the wake of global oil shocks. Such demand has continued, due to the clear environmental advantages of gas over other fossil fuels, and its superior thermal efficiency when used in power generation. Gas-fired power plants are also easier to permit and relatively quick to build. Over the past three years, the US has added 100,000 MW to the electric grid, and 90% of this is gas-fired.

According to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA), natural gas production in the US is predicted to grow to 28.5 Tcf in 2020 from 19.1 Tcf in 2000. But given recent evidence, the observed production over the last four years puts into severe question the EIA’s expectations. The bulk of the gas used in the US comes from domestic production, in many cases from fields that are several decades old and that are beginning to decline rapidly. New gas reserves are constantly being discovered, but with advanced recovery technologies, these fields are quickly depleted.

Total US demand for natural gas is expected to rise to about 33.8 Tcf by 2020 from 22.8 Tcf in 2000, Fig. 1. These projections suggest that the US could face a supply gap of at least 5.0 Tcf by 2020, according to EIA, and far more according to other estimates, such as Cheniere’s, Fig. 1. Consequently, substantially increased gas imports will be required to meet future shortfalls.

|

Fig. 1. US gas production versus consumption, Tcf.

|

|

Pipeline imports of gas from Canada already make up about 15% of total US consumption. Canada may not be able to sustain increasing volumes of exports to the US, due to its own increasing demand for natural gas, and the aging of the Western Canada sedimentary basin. Recent trends show that due to decreasing, initial gas well productivities, and high production decline rates, higher levels of drilling activity are necessary to maintain current output levels.

Alternative sources of domestic gas supply include building a pipeline to provide gas from Alaska’s North Slope to the Lower 48 states; developing onshore gas resources in the Rocky Mountain region; and developing offshore resources in the Pacific, the Atlantic and the Eastern Gulf of Mexico (GOM) Outer Continental Shelf (OCS). Natural gas from Alaska would not be competitive in the Lower 48 states (and Canada), until gas prices increase enough to make the production and transportation system economically viable.

| TABLE 1. Global, proved natural gas reserves, top 20 countries |

|

|

Additionally, a supply gap will remain, even after the delivery of Alaskan gas commences, as access to much of the offshore resources in the eastern GOM and the onshore Rocky Mountain region is limited, or prevented, by federal and state laws and regulations. However, worldwide proven gas reserves are estimated to provide at least 60 years of supply at current global consumption rates. The bulk of these reserves are in Russia, Iran and Qatar. Table 1 details these reserves and the top 20 countries. These countries and others have gas reserves well in excess of local demand. LNG is an excellent alternative to monetize these gas reserves.

Fig. 2 shows LNG demand prospects in North America. For years, the US market has been dominated by a surplus of supply and low gas prices, giving little opportunity for LNG. Starting in 2000, tight supply capacities led to a sharp rise in prices that peaked at $10/MMbtu in January 2001. From 2003 to 2005, the natural gas price started escalating again, peaking at almost $17/MMBtu. A resumption of LNG imports appears viable. Are LNG producers ready to take the risk of US netback market price fluctuations for large volumes?

|

Fig. 2. LNG demand prospects in North America.

|

|

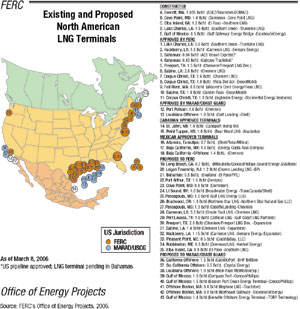

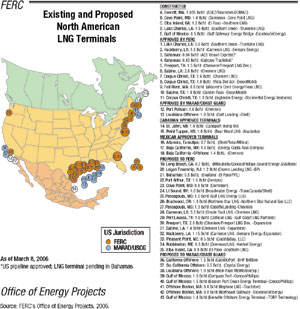

TERMINALS

The growing North American demand for natural gas has resulted in a dramatic increase in the number of LNG receiving and regasification terminals that are planned, proposed and under construction. Choosing a site for an LNG terminal requires developers and designers to understand and balance a myriad of technical, operational, economic, supply, marketing, environmental, security and community issues. These numerous, and often opposing issues have led the industry to develop multiple LNG terminal alternatives. The alternatives address site-specific issues that can support a business case that will be permitted, constructed and accepted by local stakeholders.

The US has four LNG import terminals and one export terminal. The smallest and oldest LNG import facility in the US is in Everett, Massachusetts. This facility is owned by Distrigas, a subsidiary of Belgium-based Tractabel. It has a storage capacity of 3.5 Bcf and a send-out capacity of 725 MMcfgd. The Everett facility is being expanded to serve a merchant power plant located near the terminal. Plans have been announced to more than double the facility’s send-out capacity.

The LNG receiving terminal at Cove Point, Maryland, recently re-opened after being mothballed since 1980. Owned and operated by Dominion Resources, this facility is being expanded to increase its storage capacity to 7.8 Bcf of gas and send-out capability to 1.2 Bcfgd. The El Paso-owned LNG receiving terminal at Elba Island, Georgia, was re-opened in 2001 and is undergoing a significant capacity expansion. When complete, the terminal will have storage capacity of 7 Bcf of gas and send-out capability of nearly 1 Bcfgd.

The largest LNG import terminal in the US is in Lake Charles, Louisiana. This facility is also undergoing expansion to bring its storage capacity to 9.3 Bcf of gas and its send-out capacity to 1.3 Bcfgd. However, expectations are for an incremental 2.2 Bcfd of LNG imports from new terminals by 2010. The only US LNG export facility is located in Kenai, Alaska. This facility exports 66 Bcf of gas per year to Japan, and it has been in operation since 1969. The Kenai export terminal is operated by a joint venture between Marathon Oil and ConocoPhillips.

One of the largest misconceptions about LNG is its significance as a source of natural gas. While LNG imports have been growing rapidly, the volume remains insignificant when compared to total US consumption of gas. Currently, LNG imports account for less than 1% of total US consumption.

There are at least 113 active LNG facilities in the US, including marine terminals, storage facilities and operations involved in niche markets, such as vehicular fuel, Fig. 3. Most of these facilities were constructed between 1965 and 1975, and were dedicated to meeting the storage needs of local utilities. About 55 local utilities own and operate LNG plants as part of their distribution networks.

|

Fig. 3. Existing and proposed North American LNG terminals.

Click image for enlarged view

|

|

Currently, 16 facilities are under Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) jurisdiction in the continental US. Twelve of the facilities are land-based, peak-shaving plants that liquefy and store LNG during the summer months for send-out during winter months. The remainder are baseload LNG import terminals, Fig. 3. All US LNG import terminals were operational in 2003 for the first time since 1981, resulting in record-high LNG receipts, more than double the previous high in 1979.

There are about 40 LNG terminals that are either before FERC or being discussed by the LNG industry for North America. Six terminals are already operating on the East Coast, in Puerto Rico and in Alaska. Mexico also plans a number of new LNG terminals to receive gas from the Pacific basin for consumption on the US West Coast.

The cost of building LNG facilities has decreased, as the market has matured, thereby improving LNG economics. Improvements in the liquefaction, transport, storage and regasification processes have been developed. In addition, economies-of-scale have improved, as technology advancements allow larger facilities, including higher-capacity cargo ships.

LNG storage facilities continue to be important in meeting local utilities’ peak demand needs and as a way to store gas until needed. In addition, several niche markets, such as vehicle fuel and fuel for industrial sites in isolated areas, demand gas in the form of LNG, whether from domestic or foreign sources.

By 2010, several new LNG re-gasification terminals, located on the Gulf Coast and in the Bahamas, will be completed. A new terminal on the Baja peninsula will begin operating in 2007, serving northwestern Mexico and southern California. Additional capacity will be added by 2020. Although new terminals have been proposed to serve the US East Coast after 2015, the Gulf Coast is expected to be the primary location for new LNG import capacity. New Gulf Coast terminals are expected to account for more than 70% of US LNG terminals by 2025.

The share of total US gas consumption met by LNG imports is expected to be 15% (4.3 Tcf) in 2015 and 21% (6.4 Tcf) in 2025. LNG imports are expected to increase substantially and play a prominent role in the future, surpassing pipeline imports from Canada by 2015, Fig. 4. In the IEO 2005 reference case, Canada’s natural gas production is projected to grow at an average annual rate of 0.1%, but net imports of gas from Canada are expected to decline to 2.5 Tcf in 2009 from 3.0 Tcf in 2005, then rise again to 3.0 Tcf in 2015, before finally falling to 2.5 Tcf in 2025, Fig. 4. Although many factors can alter this outlook, the demand for LNG is expected to grow.

|

Fig. 4. US Imports of natural gas.

|

|

US LNG demand will accelerate rapidly, and this is especially true until 2010 (the growth rate is higher in the 2002 – 2010 period than in later years). This trend is due to a growing supply/ demand gap that is, in itself, a result of the inability of indigenous gas production to keep pace with gas demand growth.

Although, in the past, LNG was traded on the basis of large contracts between two points, increasingly it is now sold on a cargo basis, with each shipment traveling to the port of the highest bidder. This is a drastic change. When LNG is traded in the form of long-term contracts, the supplier is contracted to provide a specified amount of gas over a given time period, usually years. It is the contractor’s responsibility to make sure gas is available.

When gas is supplied on a spot basis, LNG prices become similar to other liquid petroleum fuels. Potentially, an LNG tanker could start off for North America but be diverted to China, because spot pricing is more favorable in Asia at the time in question. This scenario could mean trouble for the North American gas consumer, who will depend on LNG for a significant percentage of gas demand. In a price-driven market, short-term price spikes will become more commonplace. Exporting countries could form trade cartels similar to OPEC, in an effort to support a consistent pricing and supply policy.

North America may once again be at the mercy of foreign petroleum producing cartels, only this time it will certainly include, among others, Former Soviet Union countries. This may encourage unconventional gas sources, such as coalbed methane (CBM) and shale, to close the demand gap.

SUMMING THE BIG PICTURE

In conclusion, while natural gas is poised to gain an even larger share of world and US energy demand, becoming in a few decades the premier fuel of the economy, there are several bumps on the road. One of the most obvious indications is the unprecedented, recent escalation in the price of gas.

But there are other important issues. First, domestic gas production in the US is declining, in spite of large increases in the number of rigs drilling new gas wells. Second, LNG will be marshaled to fill gas demand, but the process, again, will not be uneventful, and it will take some years for LNG to be established to its full potential. At that time, gas prices are likely to decline and stabilize for several decades.

Third, LNG will adversely affect the development of unconventional gas resources, such as CBM and shale gas. Only niche markets may survive, and only with overwhelming proof of economic viability. Fourth, natural gas output capability from Alaska’s North Slope is quite tenuous and may never be built, again because of LNG, but also because of large potential resources in the Cook Inlet and CBM in south-central Alaska.

|

THE AUTHORS

|

|

Saeid Mokhatab is a member of the International Advisory Board for EMERTEC Research & Development Ltd, in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, as well as an advisor of natural gas engineering research projects in the Chemical and Petroleum Engineering Department of the University of Wyoming. His expertise lies in the area of hydraulic design and engineering of multiphase flow transmission lines and gas processing plants. Previously, Mr. Mokhatab worked as a researcher at Cranfield University, England, working on TMF3 Consortium Sub-Project VII: Flexible Risers. He has participated as a flow assurance consultant and engineering manager in various projects. He has published more than 40 academic and industrial oriented papers and reports. Mr. Mokhatab served on the Board of SPE’s London Section during 2003 – 2006, and is currently a member of the ASME/ PSD Offshore Technical Committee, ASCE Pipeline Research Committee, GPA Europe, SPE and Sigma Xi.

|

|

|

William A. Poe is a Houston-based consultant with over 24 years of experience in chemical and gas processing plant design and operations. He has developed APC and optimization master plans for such companies as Saudi Aramco, Statoil and PDVSA, as well as automation and advanced process control feasibility studies for about 100 plants worldwide. He spent over a decade in natural gas processing operations and engineering with Shell Oil. Mr. Poe assumed technical leadership of Continental Controls via acquisition by GE. After joining GE as part of the Continental Controls acquisition, he became vice president of that division. He has authored more than 25 technical papers, and received the GE Innovators Award in 1999.

|

|

|

Michael J. Economides is a professor at the Cullen College of Engineering, University of Houston, and managing partner of a petroleum engineering and petroleum strategy consulting firm. Previously he was the Samuel R. Noble professor of petroleum engineering at Texas A&M University, where he served as chief scientist of the Global Petroleum Research Institute. Prior to that, Dr. Economides was director of the Institute of Drilling and Production at Leoben Mining University, Austria. Before that, he worked in various senior technical and managerial positions with a major petroleum services company. Publications include authoring or co-authoring of 11 professional textbooks and books, including “The Color Of Oil” and 200 journal papers and articles. He has had professional activities in over 70 countries.

|

|

|