What's new in exploration

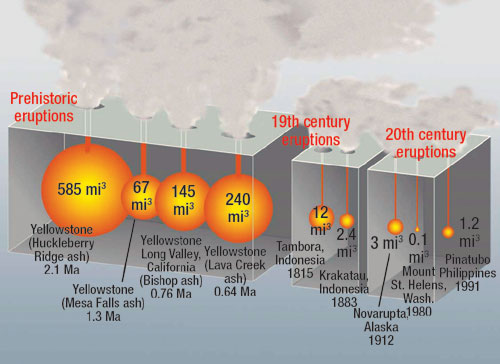

Super-eruptions. If you saw the recent BBC broadcast on this subject, this may be mostly rehash, but just in case... For some years, I’ve been watching the rhetoric on so-called super-eruptions heat up. The Indonesian tsunami disaster has been bringing it to the forefront again. Like their name implies, these are extraordinary volcanic eruptions on a scale unknown in recorded human history. The legendary eruption of Krakatoa in 1883 was heard up to 2,850 mi away and over 1/13 of the Earth’s surface. Ash fell as far as 3,800 mi distant. Tsunamis towered more than 130 ft above sea level and killed at least 36,000 people. Then there’s the death and destruction from the 1980 eruption of Mt. St. Helens and the 1991 eruption of Mt. Pinatubo. As the figure on this page shows, all are veritable pimples on the Earth’s butt compared to the behemoth eruptions of the past. And undoubtedly, in the future.

The super-eruptions of the past had a colossal impact on a global scale. What would happen if one of these planet pummelers were to go off tomorrow? Well, you probably could guess. The Earth would ring like a bell for days. The sun would disappear from view for several weeks or months, with thick haze lasting for years; Earth would get colder; and food production would be devastated, causing mass starvation. It would have the effect of a 1.5 km space rock hitting Earth. Space rocks that large only hit the Earth once every 400,000 years or so, while the equivalent super-eruption is about once every 100,000 years, at a minimum. Annual meetings have produced contingency plans for space rocks that involves nudging the object a tiny bit with rockets – which is all that you need to miss Earth, assuming that you start soon enough. But what can you do about a super-eruption? For many years, geophysicists have been saying that Yellowstone National Park is a likely place for a super-eruption to occur. This is based, in part, on the fact that there is a lot of magma close to the surface, it’s a tectonically active region, there have been several of these mega-eruptions in the Western US in the past (see figure), and it’s underlain by the remnants of a subducted plate. Greater understanding of how all this works is ongoing and one of the goals of project EarthScope, a seismic network that will eventually investigate much of North America (see this column, June 2002).

The BBC docudrama portrayed such an event, with rock, gas and ash raining down across three-fourths of the US. Hundreds of thousands are killed, crops destroyed, and so on. The thrust of the show was to point out that no one has any contingency plans, with several geologists saying that there should be some established. I suppose that, since these eruptions cannot be predicted or prevented, canned food and a gas mask might be the best that one could expect. A Hollywood movie can’t be far behind. Earthquake cycles: Old meets new. Reader John Simpson sent me his 1967 paper, published in the Earth and Planetary Science Letters (3, pp. 417-425). His conclusion was that solar activity, as indicated by sunspots, radio noise and geomagnetic indices, plays a significant but by no means exclusive role in triggering earthquakes. “Maximum quake frequency occurs at times of moderately high and fluctuating solar activity. Terrestrial solar flare effects... are the actual coupling mechanisms that trigger quakes.” The graphs in his paper allow “probabilistic forecasting of earthquakes that, when used in conjunction with local indicators, may provide a significant tool for specific earthquake prediction.” Reader Fred Aminzadeh (dGB-USA, past SEG vice president) noted that earthquake prediction might be aided with some of the newer neural network algorithms. The graph on this page is one of several in Simpson’s paper, showing the probabilistic association between sunspot cycles and earthquakes.

|

||||||||||||||

- Prices and governmental policies combine to stymie Canadian upstream growth (February 2024)

- U.S. producing gas wells increase despite low prices (February 2024)

- U.S. drilling: More of the same expected (February 2024)

- U.S. oil and natural gas production hits record highs (February 2024)

- Quantum computing and subsurface prediction (January 2024)

- U.S. upstream muddles along, with an eye toward 2024 (September 2023)

- Applying ultra-deep LWD resistivity technology successfully in a SAGD operation (May 2019)

- Adoption of wireless intelligent completions advances (May 2019)

- Majors double down as takeaway crunch eases (April 2019)

- What’s new in well logging and formation evaluation (April 2019)

- Qualification of a 20,000-psi subsea BOP: A collaborative approach (February 2019)

- ConocoPhillips’ Greg Leveille sees rapid trajectory of technical advancement continuing (February 2019)