Protecting the Environment

An update on the regulation of geophysical operations to protect marine life

A remarkable development affecting US waters – that there was no significant impact of seismic operations on marine mammals – may not be enough in a world of competing government agencies.

Chip Gill, President, International Association of Geophysical Contractors

Broadly, human activities affect marine life in many ways. Fishing, shrimping, gathering shell fish and lobsters and aquaculture all take a significant toll. In fact, by-catch from global fishing and related activities are estimated to kill 300,000 to 600,000 marine mammals annually (Read, et. al, to the International Whaling Commission, 2003). Other human activity can have a seriously negative effect on marine life: effluence and other pollutants running down rivers; vessels in open waters and (especially recreational) vessels in bays striking marine mammals with regularity; toxic and other pollutant releases, etc. Yet naval activities, particularly sonar, shipping, researchers and the E&P industries all produce significant sounds in the oceans. The specific concern is over possible negative effects that manmade sound may have on marine life.

Recent news events, and concerns surrounding them, only serve to focus attention on this issue. Mass stranding events of various whale species, mostly linked in press reports to naval operations, are cause for great concern. Geophysical operations are not immune either. In 2002, press reports linked a stranding of two beaked whales in the Gulf of California to scientific seismic operations being conducted by the R/V Ewing, operated by Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory for the National Science Foundation. A further cause for focus on sounds can be linked to efforts to expand the body of knowledge in this area. As new theories are put forth, they receive significant media attention, often fanned by advocacy groups.

The E&P industry is receiving increasing attention on the effects that sound from E&P operations might have on the health and well being of marine life, and of whales and dolphins in particular. Without question, the loudest sounds the E&P industry makes in the oceans are those made by seismic streamer operations. And while many attempt to link this acoustic activity to the world's navies, they are very different.

Current naval tactical sonar operates in the mid-frequency ranges above 3,000 Hz, have pulses that last for a duration of seconds, have a rapid duty cycle, have very high source levels and are directed outwards. These characteristics appear to be a problem for some species of whales under some conditions. In contrast, oilfield seismic acoustic emissions are impulsive, lasting less than 10 ms, operate at very low frequencies (90% total energy below 300 Hz) and are directed downward. Not withstanding these differences, many who have already concluded mass strandings are associated with naval sonar activities are now trying to extend those concerns to oilfield-related seismic operations.

It is difficult to respond to this issue. In general, there is a lack of knowledge of the behavior of many of these animals. Some have been brought into captivity and studied in that unnatural setting, but there are many species about which little is known. Animals such as beaked whales are exceedingly shy and live in deepwater environments, many of which are remote. Many species are too large to bring into captivity to study. They can range over broad areas of the ocean, and often, their seasonal distribution is not known. Some animals, such as Sperm whales and beaked whales, spend most of their life under water and are therefore inaccessible most of the time. Sperm whales feed at average depths of 1,000 m (one was recorded diving for almost 2 hours, going down almost 2,000 m). Given all this, it is no wonder gaps exist in our knowledge of these animals.

Whales and dolphins evoke much emotion in many people, and any suggestion that oil and gas operations might be harming them often provokes an outcry. Some environmental advocacy groups, well aware of this fact, are increasingly seeing this as an opportunity to fan the flames in fundraising efforts.

In the policy debate surrounding this issue, the oil and gas industry finds itself in a position of having to prove a negative. That is to say, as allegations are made about negative effects of E&P operations on these animals, no matter how unfounded, our industry is placed in a position of having to prove that we are not having the effects that are alleged. With the level of knowledge (and gaps therein) that currently exist, proving the negative is difficult at best.

A precautionary approach is generally advocated as a reasonable way to manage potential negative effects from our acoustic emissions. However, the geophysical industry believes that, with most whale and dolphin species, the management practices suggested are not warranted. Our operations are transient, moving through an area over days, weeks, or sometimes months. Low-frequency emissions cannot be heard by most species – much less cause harm. Species that merit greater caution, such as the Baleen whale (which includes Humpback, Blue, Bowhead, Fin, Right, Grey and Sei whales) are generally migratory, not remaining in areas for long stretches of time, and do not all cover all regions of the oceans. A precautionary approach does not seem warranted much of the time. However, regulations to mitigate potential impacts from our operations are becoming ever more precautionary and are increasingly being enacted.

An additional difficulty comes from the state of our industry. As those in the E&P industry know, our industry has downsized significantly. There are fewer people who provide the critical resource – time and intellect – to work this issue. And many companies have decentralized operations, making a coordinated, collective global response exceedingly difficult to organize.

Despite the difficulties in the global E&P industry, of which the seismic industry is a vital part, it is responding to this issue. After struggling in 2002 with our response to the stipulations in MMS Lease Sale 184, we, as an industry, are now much more knowledgeable about this issue and prepared to address opinions, articles and allegations, many of which may not be well founded or which may be offered as knowledge when they are in fact speculation. We have made tremendous progress in understanding the exact nature of our acoustic emissions in the higher-frequency ranges and how they propagate directionally. We have also made significant progress in identifying the knowledge gaps most critical to our issue, and have begun to address them. And we are in a much better position to highlight junk science when it is offered in the policy debate.

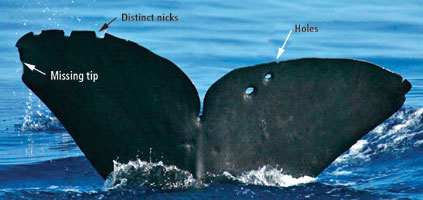

The E&P industry has been heavily involved in research efforts, Fig. 1. Australia has long been engaged in collective, collaborative research. Industry members operating in the North Sea have likewise long been engaged in various research activities, as have those in more problematic areas such as operations in and around Arctic waters. More recently, the industry has formed a research coalition to take advantage of the opportunity to partner with the US MMS in its Sperm Whale Seismic Study (SWSS) in the Gulf of Mexico, Fig. 2. Other ongoing industry efforts involve signal characterization, the development of an open-source software platform for passive acoustic monitoring, and enhancement of existing satellite tagging technology.

|

Fig. 1. IAGC-member vessels Speculator and Gyre, participating in Sperm Whale Seismic Study.

|

|

|

Fig. 2. During the Sperm Whale Seismic Study, flukes are photographed as they provide a unique ID for each whale.

|

|

The activity by regulators worldwide in this issue is clearly growing. While areas such as Brazil, portions of West Africa, Venezuela and Russia are at various stages of looking at their regulation of this issue, other jurisdictions are much more advanced.

Canada'sOceans Act (S.52.1(a)) has regulated offshore seismic operation in Canada since 1997. In spring of 2003, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) began a large scale research effort to further investigate the effects of seismic noise resulting from petroleum exploration on cetacean life, particularly in the Scotian shelf area. The bulk of these projects were complete by June 2004, and the DFO is now proposing regulations to uniformly mitigate seismic noise in Canadian waters.

The new regulations, which will become part of the marine environmental quality provisions of the Oceans Act, will be developed through a collaborative approach with federal and provincial regulatory authorities as well as industry. The DFO also proposed a new system of Regional Strategic Environmental Assessments (RSEAs), ensuring that developmental proposals take regional environmental characteristics and sensitivities into account. RSEAs will not preclude the filing of Environmental Assessments (EAs) now required, but are intended to work together with EAs to specify potential environmental impact by region. In May 2004, the Sable Gully area was officially designated as the second Marine Protected Area under the Oceans Act, and seismic exploration activities in the area are now prohibited. Eleven other marine areas are now being considered for MPA designation.

In Australia, the environmental protection legislation governing offshore seismic operations is the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act). Australian requirements for marine mammal observation are already among the most stringent in the world, with a 3,000-m radius of observation and 10 min. of observation per hour required. Observations must begin 90 min. before ramp-up procedures, and two hours must pass after a sighting incident. In July 2004, the Department of the Environment Heritage (DEH) issued an “Invitation to Comment” on the “Guidelines on the Application of the EPBC Act to Interactions between Offshore Seismic Operations and Larger Cetaceans.” This document is intended to advise seismic operators of how the DEH plans to implement certain provisions outlined in the EPBC Act.

Like other Australian regulations, these guidelines are species specific, and primarily treat the protection of whales. Leaders in the seismic industry who have reviewed the document are concerned that it may effectively tighten restrictions already in place, specifically, in recommending additional procedures such as aerial surveys to detect marine mammals (a substantial risk to human life). There is also some concern that this document suggests that the E&P industry should undertake even greater responsibility in funding marine mammal research (industry funding is already significant). At this writing, comments from all parties have been received and are being considered by DEH. Industry is awaiting the next step.

In the UK, the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) and its environmental consultancy, the Joint Nature Conservation Commission (JNCC), have recently reviewed their guidelines. While, from industry's perspective, there were no significant structural changes to their approach, there were changes in the areas of marine mammal observers and their reporting. Additional questions have been raised about the use of passive acoustic monitoring and about the validity and effectiveness of ramp-up as a mitigation measure. All indications suggest that these guidelines will again be reviewed in these areas in the near future.

In the US, the MMS recently issued its Programmatic Environmental Assessment (EA) for geophysical operations in the Gulf of Mexico. This EA, which began in 1999, recently concluded with a Finding Of No Significant Impact. While initially reassuring to many in the E&P industry, NOAA Fisheries, who is the ultimate regulator under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, has already indicated that an Environmental Assessment is not adequate under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), and that they intend to develop an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) as the NEPA document for the upcoming geophysical rulemaking in the Gulf of Mexico.

Regarding that long-anticipated rulemaking under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, the MMS, after initially filing a petition for rulemaking with NOAA Fisheries in late 2002, has for nearly a year been working on an amended petition that it intends to file in the near future. This anticipated filing will kick off an intense period of scrutiny surrounding this issue in the US Gulf of Mexico. Along with the concurrent EIS process, this scrutiny will involve public hearings and public comments, all of which can be anticipated to draw further focus and attention to this issue.

Further, NOAA Fisheries has convened an expert panel to develop new Noise Exposure Criteria that will presumably replace the 160/180 dB criteria developed by the HESS team in the mid '90s. This process appears to be more difficult than first envisioned, and can easily be expected to become very political in nature. Once new criteria are developed and put in place, they will become the guiding factor for US regulatory action. It is also likely that any new US Noise Exposure Criteria will be closely watched by other global regulators and considered by them in any review of their regulatory approach. Their development requires close monitoring.

As if the foregoing was not enough, in late 2003, the US Marine Mammal Commission (MMC) was directed by Congress to consider this issue in a series of forums to “share findings, survey acoustic ‘threats' to marine mammals, and develop means of reducing those threats while maintaining the oceans as a global highway of international commerce.” In response, the MMC formed a 28-member Acoustic Impacts Advisory Committee. This committee includes representatives from the environmental community, academics, researchers, regulators as well as members of the E&P industry.

Along with colleagues from Shell and ExxonMobil, the author serves on this Federal Advisory Committee, which now has numerous subcommittees at work. The full committee has met four times (three days each) and there have been three separate associated workshops. This effort is intended to culminate in a report to Congress in mid-2005, yet it is difficult to see how the committee will meet that deadline. As the deliberations of the full committee proceed, the differences of opinion are becoming more pronounced, and broad consensus in the final report seems unlikely. Yet, it is essential that the E&P industry is represented in this process – as time consuming as it might be.

The deliberations in the MMC Advisory Committee provide a clear window into the complex and diverse nature of the policy debate surrounding this issue. One has to simply sit through the discussions with the diverse constituents who are represented around the table to get a sense of the magnitude of this issue for the E&P industry. Stay tuned.

|