|

Vol. 225 No. 4 |

|

|

| ØYSTEIN NORENG, CONTRIBUTING EDITOR, NORTH SEA |

Norway and the UK: Promises and problems. Upstream activity on the Norwegian and UK Continental Shelves is dwindling. Fields are depleting, and platforms are shutting down. Exploration decreases, and the discoveries made are of diminishing sizes. Few major development projects remain, and investment levels are falling.

After the UK, Norway has matured and shows no signs of further growth, due more to politics than geology. Both countries need to stimulate increased exploration; develop new, smaller fields linked to infrastructure; and increase field output. Industry executives claim that Norway's high petroleum tax rate is the major reason why oil companies do not consider many projects to be sufficiently profitable. Although Norway's oil output will decline (unless industry incentives improve), natural gas is set to increase further.

Even if Norway is a maturing province (measured by frequencies and sizes of new finds), there is still good potential. New technology and better organization permit operators to move into deeper waters and develop smaller prospects. The prerequisite, however, is that the government must follow up with fiscal and regulatory conditions that provide the right incentives and license more acreage.

Unless investment increases and exploration rebounds (followed by field development), reserves will not be renewed. In turn, output will gradually decline, negatively affecting Oslo's revenues, as well as Europe's degree of self-sufficiency. The case for reform in Norway is compelling.

Norway aims to capture economic rent from large oil fields, taxing net income at 78% with six-year depreciation. The absence of a ring fence means that new prospect development costs can be offset against current revenues, favoring incumbent firms and capital-rich newcomers that can buy into producing assets vs. smaller, capital-poor companies and marginal prospects. Britain, with a 40% corporate income tax and immediate depreciation, is more attractive to newcomers, but the ring fence deters marginal prospect investment. For both countries, what is not found and developed cannot be produced and taxed.

Globally, oil company expenditures for exploration have been low, because funds have been allocated to mergers and acquisitions. For many firms, it seems less expensive and risky to buy oil in the ground than to drill for it. Consequently, drilling declines are not limited to Norway or the UK.

Interest in high-cost, high-tax Norwegian prospects has waned. Norway's maturity as an oil province is due as much to rigorous regulatory and fiscal conditions as to geology (measured by costs and field sizes). Through the 1990s, the average, weighted production cost, including development, operations and abandonment, declined in both countries. Norway's cost advantage stayed constant, thanks to larger fields, indicating the importance of field size in economics. For nearly all prospects, total production costs are below $12/bbl, and operating costs tend to be below $5/bbl.

The threshold for developing a prospect in Norway is about four times higher than in the UK. By changing fiscal and regulatory conditions, Norway should be able to prolong petroleum activity for decades. So far, Norwegian fields that are developed tend to be larger and have relatively more gas than oil, compared to the UK. When geology is compared, Norway still has available a number of smaller oil fields, whose development would depend on regulatory and fiscal changes.

|

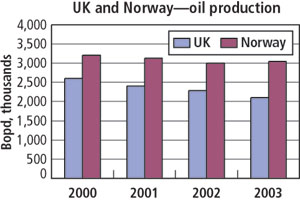

Over the last several years, UK oil production has fallen steadily, while Norway is stuck at a plateau.

|

|

In early 2004, governmental signals are mixed. The 18th Licensing Round, announced last December, invited applications for 95 blocks, three times as many as in the previous round. It includes Barents Sea acreage, especially areas close to the zone disputed with Russia. Promising acreage close to the Lofoten Islands remains off-hands, to protect fisheries. Acreage in immature parts of the North Sea and the Norwegian Sea is also included, to stimulate exploration in new areas and, hopefully, enhance reserves and production.

The extent to which industry will respond remains uncertain, as long as officials refuse to do much about taxation. Over the past few years, the Norwegian Oil Industry Association, OLF, has been busy lobbying for a general reduction in the Special Tax on all new prospects, lowering the marginal upstream tax rate to 53% from 78%. So far, officials decline any general tax cut.

This tax cut request may have been too confrontational. Other measures, such as reducing depreciation before the Special Tax (to three years, or even less, from six years), would have been more acceptable politically. Such a measure would have lowered entry barriers for smaller firms, as well as barriers to developing smaller prospects. High oil prices, however, strengthen governmental arguments against lower taxes.

In the UK, where officials face declining output, the priority is to stimulate activity through such means as more favorable licensing terms in offshore, deepwater areas west of the Shetlands. Elsewhere, new entrants are picking up assets sold by the majors, so future drilling prospects could be better than expected. The ambition is to sustain annual investment at £3 billion and combined output at 3 million boed, to prolong self-sufficiency.

Øystein Noreng is professor, Norwegian School of Management, and he holds the Total chair in petroleum economics and management. He is a regular contributor to this column.

|