Mexico's changing policies offer opportunities in natural gas

Regional Focus: MexicoMexico’s changing policies offer opportunities in natural gasThe country needs to rapidly expand gas output to meet burgeoning demand. Yet, attracting sufficient investment depends on forging a reasonable model service contractCharles Lucas-Clements, President, Economics and Consulting for the Americas, IHS Energy Group, Houston

Since Mexico privatized its petroleum industry in 1938, no outside operators have been allowed to produce the country’s vast energy resources. It appears that Pemex needs to rapidly expand its technological capabilities to effectively produce some of the more complex areas. The most effective means to accomplish this goal is to bring in outside operators with specific technical experience and success in certain geologic formations. Pemex has announced a licensing round for 2002, but the proposed service contracts are rather complex. In their present form, they may not be viewed to be as financially lucrative as necessary to attract the kind of interest that Mexico needs from its initial licensing round. Addressing the Challenge Mexico’s leaders have some hard choices to make, to ensure the economy’s stability and continued growth. Fundamentally, the country has developed, or is in the process of developing, its entire, current, energy-reserves base. To survive, it must discover more and release the undiscovered reserves, which are undoubtedly there. Should Mexico’s leaders opt to avoid making a decision in the next one to two years, the die would be cast into a particular, precarious set of consequences. These would involve power cuts for some, and a stagnation of the Mexican economy for all, from 2004 onward. Key issues for the government will be:

The Mexico Gas Study A Mexican gas study recently completed by IHS Energy Group took a comprehensive look at the natural gas business in Mexico as it exists prior to the country’s first licensing round. To prepare this timely study, we used our company’s own comprehensive E&P databases, as well as in-house knowledge and expertise. In addition, we also collected and evaluated industry information, especially from the Mexican government and Pemex. This allowed us to evaluate as many factors as possible that were relevant to the overall situation. The study covered all aspects of the Mexican E&P industry, including:

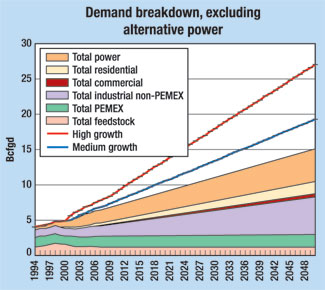

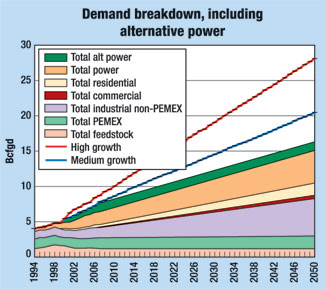

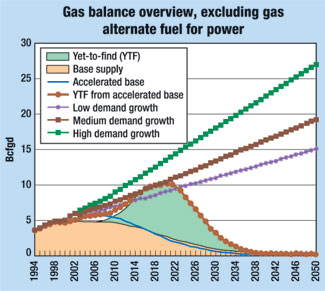

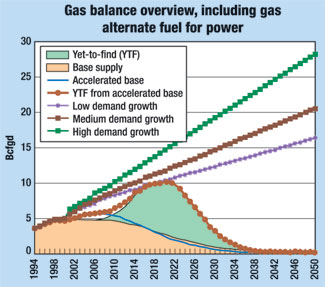

On the supply side of the equation, there are approximately 50 Tcf of remaining, recoverable gas reserves in Mexico. The potential exists for discovering an additional 50 Tcf of economically recoverable gas reserves during the next several decades. Mexico’s known reserves are almost entirely developed to some degree, or are presently under development or appraisal. These reserves are capable of generating nearly 5 Bcfgd under current E&P programs that Pemex has in progress. By securing additional investment to develop the known reserves, we think it is possible for Mexico to increase its gas production level to approximately 6 Bcfgd. Depending on timing and investment, the undiscovered reserves may be identified, discovered and developed in such a manner that natural gas production will just keep pace with demand during the next two decades. Delays in proceeding with a serious, sizable and ongoing program of seismic data collection, as well as drilling, appraisal and development, will certainly create ramifications for the Mexican economy within four to 10 years. For the demand side of the gas equation, there has been steady growth in Mexico’s energy usage during the past two decades. We anticipate that this trend will continue, Fig. 1. There will certainly be incentives for the government and Pemex to maximize the gas usage in the electrical power generating industry, so that the country can maintain its profitable oil exports. Thus, if gas is available, we expect the government to gradually displace oil with gas for electrical power generation. This could consume about 1 Bcfgd, when the transition is fully accomplished. During the last several years, there has been a dramatic increase in Mexican construction of gas-fueled power plants. During the next five years, completion of facilities that currently have permits for construction will boost the requirement for gas considerably. If fully used, this additional generating capacity could require approximately 2 Bcfgd.

Although smaller in scope, the privatization of Mexico’s gas distribution industry has also expanded the use of gas as a fuel for domestic and small industrial use. Overall, gas demand is expected to rise by approximately 5% to 7% annually. It will likely reach a requirement of between 6 Bcfgd and 7 Bcfgd by 2005. By 2010, demand is expected to range from 7 Bcfgd to 9 Bcfgd (excluding alternate fuel usage, which would add an extra 1 Bcfgd to these demand estimates, Fig. 2). To generate the gas production necessary to achieve these targets, Mexico is going to require considerable, additional investment in its E&P industry, which will test the current government system.

A Look Ahead The network of pipelines in Mexico that is used to transport and distribute gas to various power plants and other customers seems to be approaching capacity within the next four to six years. We anticipate new pipelines will be required to the west of Monterrey, to fuel the numerous, new electric power- generating plants that are now under construction, or have been given permits to be built in the next few years. Mexico may also need to expand its import capability to meet the country’s fuel needs in the short term. However, the financial drain of purchasing gas from the U.S. could be enormous. In the south, the pipeline network seems to have sufficient capacity to manage the situation that is forecast for the next half-decade or so. Many options are open for Mexico to achieve a balance in its gas business during the next several decades, but the country’s leaders will need to choose their course of action soon, Fig. 3. During the next two to five years, the new electrical plants now under construction, combined with the country’s desire to maintain oil exports, could easily drive Mexico to import more than 1 Bcfgd from the U.S. This gas may be inexpensive under current price scenarios, but it may not remain so for long. The likelihood of the U.S. having a gas supply crunch in this time period is more likely than not. Therefore, a return to gas prices of U.S.$5 to $8/Mcf is not out of the question.

To maintain its energy self-sufficiency, Mexico will need to launch significant efforts to quickly increase gas production from known areas. Pemex will also need to initiate exploration programs to discover the potential reserves that could meet long-term fuel needs. Alternatively, building an LNG-import terminal and re-gasification facility might also be a wise decision. It would enable Mexico’s leaders to provide an alternate gas supply and enable the hedging of Mexican gas prices during the medium term. Ultimately, as evidenced by recent discoveries (made by Shell and Unocal) in the Perdido Fold Belt, just north of the Mexican border, deepwater exploration and development have the potential to contribute heavily to Mexico’s long-term oil and gas supply. Securing funding for the exploration and development efforts described above will be as much of a challenge as the technical work involved. Several billion dollars will be required to expand the current level of Mexican gas production, and another $45 billion will be needed to discover and develop the "yet-to-find" reserves. When faced with the potentially staggering investment levels necessary to explore for and develop the hydrocarbon resources needed for future growth, many countries have taken steps to open their industries to international oil and gas companies. This has generated very positive results. These actions can often, however, take years to accomplish – time that is rapidly running out for Mexico. Pemex and the government have looked at several alternative mechanisms to facilitate the investments required. In principle, these scenarios fall under two categories. The first is a competitive contractor approach. The second comprises a number of variations of royalty / tax fiscal regimes with government participation. The first approach is essentially allowable under the current working practices of Pemex. The second would require a change in the constitution. Using models and cost estimates generated to identify various basins’ hydrocarbon potential, we have defined economic limits for several price scenarios. These basically show that the majority of the "yet-to-find" gas reserves identified should be attractive to investors, Figs. 3 and 4. However, certain areas have significant advantages. Conclusions Considerable natural gas reserves do exist in Mexico, although much of these reserves still have to be found. The ability of both Pemex and potential private investors to think globally, and to draw upon the successes and failures of previous E&P openings hosted by other countries, is the key to effectively boosting Mexico’s gas business in the timeframe and volumes required. Despite the existence of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), before any international company invests in Mexico, it must take into account the potential risks involved. These include geological, legal, and especially, contractual risks. The contractual scenario is expected to unfold by mid-2002. The contractor fee approach, the most probable contractual scenario to be adopted, is unlikely to offer more than a reasonable level of return. However, if constructed properly, then the "upsides" or production success of the contract should be able to stimulate the growth needed. However, this success is also dependent upon all risks being clearly understood by the parties on both sides of the agreement. Although it is not guaranteed to happen at all, the full opening of Mexico’s E&P industry is not likely to occur in the near future. However, whether or not it does occur will no doubt be based upon the success, or indeed the failure, of Pemex’s first offerings in the Burgos basin, and most likely, the Sabinas basin.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- What's new in production (February 2024)

- Prices and governmental policies combine to stymie Canadian upstream growth (February 2024)

- U.S. operators reduce activity as crude prices plunge (February 2024)

- U.S. producing gas wells increase despite low prices (February 2024)

- U.S. drilling: More of the same expected (February 2024)

- U.S. oil and natural gas production hits record highs (February 2024)

- Applying ultra-deep LWD resistivity technology successfully in a SAGD operation (May 2019)

- Adoption of wireless intelligent completions advances (May 2019)

- Majors double down as takeaway crunch eases (April 2019)

- What’s new in well logging and formation evaluation (April 2019)

- Qualification of a 20,000-psi subsea BOP: A collaborative approach (February 2019)

- ConocoPhillips’ Greg Leveille sees rapid trajectory of technical advancement continuing (February 2019)