|

Feb. 2001 Vol. 222 No. 2

Feature Article

|

NATURAL GAS: Igniting New Markets

Part 2: North America Outlook

There’s work to be done to meet increasing demand

The U.S. market is expanding and drilling activity is responding to

higher prices, but major new supply sources are needed to maintain a reasonable reserve life index and minimize

import increases

Leonard Parent, Contributing Editor,

World Oil

he

following North American report on natural gas supply / demand and related factors starts with a review of

U.S. supply, including reserves for key areas; wellhead price performance; drilling and demand probabilities,

including import effects; and economic growth. he

following North American report on natural gas supply / demand and related factors starts with a review of

U.S. supply, including reserves for key areas; wellhead price performance; drilling and demand probabilities,

including import effects; and economic growth.

Canadian reserve status and increased gas drilling in

the West are noted, along with the problem of reduced deliverability from shallower wells, forcing a move to

deeper, more productive formations. Comments on Mexico discuss reported reserves and potential for increased

gas development – particularly in the Northeast’s Burgos basin – in the face of continuing need

to import U.S. gas.

Summary comments describe a continuing period of "adjustment,"

with need for more exploration and drilling, with the latter facing limited rigs and personnel availability.

More U.S. imports will be needed, including LNG. Higher costs will spur more efficiency and conservation, with

the lurking possibility of federal "reregulation."

Overview

Prices will not be an issue for long. High prices are

expected to average $5.50 – $6.00/MMBtu in 2001. If much-higher prices persist, reregulation is in the

wings waiting for its entry cue.

As we move at warp speed into the new millennium, we

will have to learn to use the evolving features of e-commerce, or get run over by those that do. This

monumental change in the way we do business could very well bring about a reinvention of the gas business from

the customer back to the wellhead.

If there is one thing we agree on, it is that we are

embarking on a path of accelerated demand for gas. That is the good news. The bad news is that we must find a

way to discover and connect a huge amount of North American gas reserves – i.e., develop big-time new

supply sources – and all the while expand the infrastructure that will be needed to adapt to the

volatility – read electric generation – that will come with the new territory.

North American proved reserves at year-end 2000 totaled

about 300 Tcf. Over the next decade, we will need to discover and connect another 300 Tcf, or more, of new

reserves – out of a North American resource base of 2,600 to 2,800 Tcf – just to keep pace with

projected demand growth, while maintaining the current Reserve Life Index (RLI) – recoverable reserves /

annual production – at about 8.5 years.

Canadian exports to the U.S. will increase to close to

4 Tcf/year. And the U.S. will be a net exporter to Mexico for the foreseeable future.

U.S. Gas Supply, Production

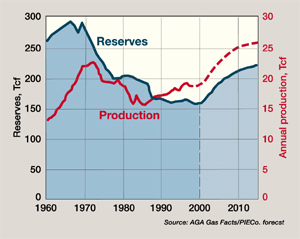

Proved U.S. reserves at year-end 2000 are estimated to

be about 162 Tcf, up about 4 Tcf from 1999, Fig. 1. That is a lot of gas, but even at that, we are having to

deal with tight supply – a condition the likes of which we have not seen for a long time. For the

Lower-48 states, the RLI at year-end 2000 is estimated to be 8.8 years, Fig. 2, equivalent to a U.S. annual

production rate of 11%. However, the reserve level is barely more than half what it was when it peaked at 293

Tcf in 1967, before starting a steady decline, Fig. 1. There is no magic number for RLI, but the lower it

gets, the delivery system loses flexibility, and shortfall in one or more market areas usually ensues.

Not all reserves are equal. Some can be produced more

rapidly than others. The principal producing areas of the U.S., as listed in Table 1, are mostly in or

adjacent to the Gulf of Mexico, or in the Rocky Mountains.

| |

Table 1. Lower-48 gas

reserves, production at year-end 1999 |

|

| |

Area |

Reserves,

Tcf |

Production,

1999, Tcf |

|

| |

Gulf of Mexico |

25.8 |

4.9 |

|

| |

Texas, East |

24.3 |

3.3 |

|

| |

Texas, West |

15.8 |

1.6 |

|

| |

New Mexico |

15.4 |

1.5 |

|

| |

Wyoming |

14.2 |

1.2 |

|

| |

Oklahoma |

12.5 |

1.3 |

|

| |

Louisiana |

9.2 |

1.4 |

|

| |

Other – 16 states |

40.5 |

3.3 |

|

| |

Total |

157.7 |

18.5 |

|

|

|

|

The Natural Gas Supply Association estimates that

offshore Gulf of Mexico reserves are being depleted at a rate of 25 – 30% per year of remaining reserves.

In other areas of the country, production / reserve ratios are substantially less, usually because the rock

formations are less porous and cannot be depleted as rapidly. Further, many reservoirs have already been

producing for many years and are well down on their respective deliverability curves.

Reserve additions in the gas-prone areas of the Gulf of

Mexico are crucial to maintaining deliverability to Eastern markets. At last count, there were 181 rigs

working in the Gulf, up from 151 a year ago. There are 37 Tcf of reserves located in non-producing reservoirs

– usually behind pipe. Of these, 11 Tcf are in federal offshore waters. That is close to 40% of GOM

reserves. Those reserves declined by 4% in 1999, but production remained essentially the same. It is

imperative that GOM exploration move ahead briskly to assure the stability of markets for gas in the Eastern

U.S.

The rig count is at a record high in the Gulf, but it

is taking a lot longer to rebuild the reserve base to eliminate tight supply concerns than many had expected.

While it is generally agreed that the reserves are in the ground, and that wellhead prices are sufficient to

attract adequate financial support, we have moved on to an exploration lifestyle that is described by some as

"just in time." It now appears that the concept has a two-year or more lead time from reaction to a

price signal to meaningful reserve growth.

As a footnote, North Slope reserves, about 16 Tcf, were

dropped from the reserve base in 1986, because a number of studies indicated that the cost of building

transportation facilities from the North Slope to the Lower-48 was – and would continue to be –

prohibitive. However, high prices have revived the prospect of building a pipeline to deliver gas from the

North Slope and the McKenzie Delta, probably about 2010.

A historical note.

U.S. gas consumption peaked at 22.6 Bcf in 1973, at about the time of the "oil crisis." Production

fell off sharply, dropping below 20 Tcf/yr amid concerns over deliverability. As it turned out, the production

decline that began in 1973 continued on for 10 years until 1983, before bottoming out at 15.8 Tcf/yr. FERC

Order 636, and others, were put in place to stimulate the gas business. Significant changes that flowed from

the FERC orders were the shift away from pipeline ownership of long-term contracts for reserves and the

evolution of a spot market. Conceptually, the idea was to provide a means of opening the market to all

players. The downside of the outcome is that the market is made by players in New York City.

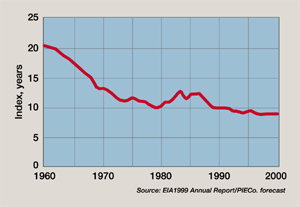

Reserve Life Index (RLI).

This Index is used by many as a marker for the point where too much gas becomes not enough, or vice versa. It

is another way to describe tight supply As shown in Fig. 2, the U.S. RLI has been in decline for virtually the

entire time since 1960. As the reserve base shrinks, or simply stays flat, an increase in demand will push the

marker down. Since 1996, the RLI has been below 9.0 years, a warning that – without some meaningful

action on the part of the players – tight supply troubles and high prices could raise the issue of

reregulation. And sure enough, we are in the middle of tight supply and some are calling for action.

Wellhead prices. By

1984, the average wellhead price of gas had risen to $2.66 before slipping back during the "gas bubble"

years that followed, Fig. 3. The post-NGPA drilling boom passed into history while producers were struggling

to stay alive in a low-price environment. Over time, average wellhead prices have moved in a fairly narrow

range, as shown in Fig. 3.

However, given what has happened to the reserve base in

recent times (modest decline) and currently-tight supply, we appear to be at an inflection point in gas price,

as is evidenced by recent events on the NYMEX, when spot prices touched $10/MMBtu before dropping back

slightly. The outlook is for spot prices to come down from the 1999 – 2000 winter peak and average about

$4.50 – $5.00/MMBtu for the coming year.

In 2001, domestic gas production is projected to reach

19 Tcf, a 500 Bcf increase over 1999. Delays in Gulf of Mexico production and only marginal growth in the rest

of the Lower-48 led to relatively unchanged production in 2000.

Unless deliverability improves substantially as a

result of the record gas-well drilling activity going on, it is not likely that prices will moderate

noticeably. Heightened conservation, fuel switching and efficiency gains will very likely take some of the

edge off gas market growth.

Drilling.

Gas-well drilling had already reached record levels well before the current runup. It is estimated that 15,000

gas wells were drilled in 2000, up 5,000 from 1999. During the 10-year period, 1990 – 1999, about 100,000

gas wells were drilled, connecting nearly 190 Tcf of new reserves. In the next 10-year period, we need to

connect about 300 Tcf of new reserves to meet projected demand and maintain an RLI of about 8.5. The outlook

is for 18,000 gas wells in 2001. The IPAA reports that producers are moving as fast as they can to put more

rigs and crews in the field.

U.S. Demand

U.S. natural gas consumption in 2001 will probably

reach about 22.6 Tcf, up from an estimated 21.9 Tcf in 2000, an increase of about 700 Bcf. Residential and

commercial usage will lead the way, partly because of the below-normal weather early on in 2001.

Gas imports increased by an estimated 4.5% in 2000, and

are expected to increase substantially in 2001 with the advent of additional pipeline capacity accessing

Western Canada gas supplies, and increased deliveries from offshore Nova Scotia. LNG is back in the picture.

Renovations of the Cove Point LNG terminal in Maryland and the Elba Island LNG terminal in Georgia are moving

ahead quickly to take advantage of the tight supply situation and price spikes.

2001 Outlook

Economic growth, electricity demand and normal weather

are expected to drive U.S. energy consumption in 2001 to 96 quads, an increase of 1.8%.

Consumption of all fossil fuels is expected to

increase. Increase in coal consumption will be driven by higher utility demand, as well as stronger oil and

gas prices. Natural gas consumption is expected to increase in 2001, driven mainly by higher usage in

weather-sensitive markets. Stronger gas prices, particularly in comparison with less-expensive coal and

residual oil, could serve to limit the growth of gas markets in the utility sector. Nuclear energy consumption

is expected to decline in 2001. Hydropower availability is expected to increase slightly, assuming normal

rainfall.

Energy efficiency – the measure of how well we

utilize our energy resources, given higher prices for gas and oil – will likely improve as people find

ways to cut energy waste.

Gas demand for industrial uses is expected to increase

in 2001. Gas consumption by electric utilities is expected to increase due to increased generation, an

increase of 4.7% year-over-year. Gas exports, primarily to Mexico, are expected to increase substantially as

the Mexican economy makes some headway. Gas imports from all sources will increase to 4+ Tcf in 2001.

Storage providers have taken on additional roles, of

arbitrageurs of price differentials between seasons and regions. Storage availability will be a significant

factor in the location of large, gas-fired electric generation plants, with their highly-volatile load

characteristics. Distributed generation is catching on and will have a role to play in meeting the market for

electricity.

E-commerce is the name of the game. It is the tail that

wags the tiger. The efficiency of e-transactions will be the vehicle operators will use to reduce the cost of

doing business.

Canada

Canada has about 55 Tcf of remaining reserves out of a

650+ Tcf resource base, Table 2.

| |

Table 2. Canada:

additions, production and reserves, Tcf |

|

| |

|

1994 |

1995 |

1996 |

1997 |

1998 |

1999 |

2000

est. |

|

| |

Additions |

2.8 |

5.8 |

1.8 |

1.6 |

4.2 |

4.5 |

4.5 |

|

| |

Production |

5.0 |

5.0 |

5.6 |

5.6 |

5.6 |

6.0 |

6.5 |

|

| |

Remaining reserves |

63.0 |

64.0 |

60.0 |

59.0 |

58.0 |

57.0 |

55.0 |

|

| |

R/P ratio |

12.6 |

12.8 |

10.7 |

10.5 |

10.4 |

9.5 |

8.5 |

|

|

|

|

Canadian gas marketing has experienced strong growth in

recent years, to the extent that production has outstripped reserve additions for the past several years,

resulting in a continuing decline in remaining reserves. Exploration is up sharply, particularly in British

Columbia, and is starting to edge into the Northwest Territory. This would fit in well with the prospects for

a gas pipeline from the North Slope of Alaska.

Western Canada is second only to the U.S. Gulf of

Mexico and environs as a gas supply resource. In fact, the majority of Canada’s gas reserves are located

in the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin (WCSB), with a lesser amount located offshore Nova Scotia. The decline

in the R/P ratio raises speculation on the ability of Canadian supply to meet both Canadian and export markets

in the short-term.

Gas well drilling has been on the rise since 1995, and

is expected to pass 8,200 wells in 2000, 8,800 in 2001 and 9,000 in 2002 – a 40% increase between 1999

and 2002. Recent production data show that there has been a substantial decrease in initial productivity rates

for wells across the WCSB, due in part to the drilling of an increasing number of shallow wells. It is

expected that drilling activity will increase most in the western and northwestern areas of the WCSB, which

have deeper and more productive wells – albeit more expensive to drill.

Despite the drilling of a record number of wells,

deliverability has increased only marginally. The per-well average has been declining, due in part to the

drilling of an increasing number of low-deliverability shallow wells. To offset the annual decline in

production from existing wells, production from new wells must amount to 20% of current production, a

formidable barrier to increasing production.

Mexico

Mexico is reported to have 63 Tcf of proved reserves

included in a resource base estimated to be 600+ Tcf.

Mexico has large gas resources relative to its rate of

production and consumption. It has the potential to be both a major producer and consumer, and it is certain

to take on a more significant role in North American gas development in the future. The Mexican government is

aggressively promoting gas industry development. To that end, the government has opened up the transmission,

distribution and storage sectors of the gas industry to competitive bidding by private industry, as well as

electric generation. PEMEX will, for the time being at least, retain its monopoly on exploration and

development activities.

Gas production is expected to increase substantially,

Table 3. Most of the increase will result from the development of gas fields in the Burgos basin in

Northeastern Mexico, aimed at doubling production to 1.4 Bcfd by 2001.

| |

Table 3. Mexico:

Production, demand, imports, Bcf |

|

| |

|

Production |

Demand |

Imports |

|

| |

1995 |

997 |

1,052 |

61 |

|

| |

2000 |

1,515 |

1,608 |

94 |

|

| |

2001 |

1,554 |

1,681 |

127 |

|

| |

2002 |

1,625 |

1,809 |

184 |

|

| |

2003 |

1,653 |

1,878 |

225 |

|

| |

2004 |

1,682 |

1,913 |

230 |

|

| |

2005 |

1,777 |

2,007 |

230 |

|

| |

2010 |

2,111 |

2,342 |

230 |

|

| |

2015 |

2,519 |

2,749 |

230 |

|

| |

Source: GRI Insights, November

2000 |

|

|

|

|

However, Mexico is expected to be a net importer of gas

from the U.S. for the foreseeable future.

Summary

The data tend to point toward a period of adjustment.

Exploration will have to move into high gear to keep pace with dramatic increases in demand in the coming

decade. Gas-well drilling will continue to increase, subject only to the availability of rigs and crews.

E-commerce will dominate the way we do business.

Canada will be stepping up its resource development

program. Mexico will be moving up the curve of energy development and utilization, but will need gas from the

U.S. for the foreseeable future.

Look for more imports, including LNG, to bolster U.S.

supply alternatives. Look for energy efficiency and conservation to come back into vogue, as consumers seek

ways to deal with higher energy costs. There may not be a 30 Tcf market out there.

The author |

|

Leonard V. Parent,

a World Oil contributing editor, holds a BS in chemical engineering from Purdue University, and has been

active in the gas business since 1950, beginning with Natural Gas Pipeline Co. of America. He later joined

Trunkline Gas Co. in Houston and, in 1968, was appointed to corporate planning for Panhandle Eastern. Mr.

Parent took early retirement after 26 years with Panhandle and Trunkline, and embarked on a second career

as a consultant and publisher of The Gas Price Report and The Gas Price Index. |

| |

|

|

|

Part 1:

Exploration Methods |

|

Part 3: HP/HT

Drilling and Completions |

|

Part 4: Tight

Formation Stimulation |

|

Part 5: Sour

Gas Handling |

|

Part 6:

Anomalously pressured zones |

|

Part 7:

Gathering and Compression |

|

Part 8:

Monetizing Stranded Gas |

|