OPEC cannot manage world oil markets with a price band

OPEC cannot manage world oil markets with a price bandOther commodity organizations (tin, rubber, bauxite and coffee) have more power than OPEC, yet they were not able to manage their markets through price bands. Any success that OPEC achieves (little or none to date) may be due to good luck rather than an ability to manage world oil marketsDr. A. F. Alhajji, Contributing Editor, and Research Professor, Colorado School of Mines, Golden, Colorado

Current OPEC President Ali Rodriguez announced the unofficial price band of $22-to-$28/bbl after the group’s meeting last March. He stated that OPEC would increase production automatically by 500,000 bopd when prices exceed $28/bbl for 20 consecutive days and would cut output by 500,000 bopd when prices decline below $22/bbl for 20 consecutive days. OPEC theoretically does not want oil prices to stay above $28/bbl, because such rates may hurt world economic growth. A decline in global GDP (gross domestic product) growth will reduce oil demand. Consequently, OPEC oil revenues will decline, due to lower prices and lower exports. In addition, higher oil prices will reduce oil demand, because they promote efficiency, substitution and new technology. At the same time, OPEC does not want oil prices to decline below $22/bbl for an extended period of time. Group members certainly want their share of the "new world economy." The experience of 1998 and early 1999 is still today’s news. Low oil prices depleted crude reserves; increased the income gap between consumers and producers; created friction among OPEC members, as well as between OPEC and non-OPEC producers; and led to the imposition of tariffs on oil imports in consuming countries. In addition, low crude prices led to economic hardships within the producing countries. These included declining oil revenues; budget deficits; budget cuts and canceled projects; borrowing and debts; deterioration of balances of payments; negative economic growth; currency devaluations; and political unrest. The argument above necessitates price stability within a range that is mutually acceptable to producers and consumers. That is how the idea of a price band came about.

Control / Enforcement While the objective of a price band is politically sound, it will not work for a multitude of reasons. First among these is that such a device requires OPEC to have the ability to control and enforce it. This is not possible, because the price band that OPEC reportedly has set is high. Such prices will bring more non-OPEC oil onto the global market, prompt more cheating by OPEC members, and engender more fuel substitution and conservation. Therefore, prices will decline in an indefensible way, and the band will not hold. History has taught us that in times of panic, production increases do not lower prices. The additional oil will be bought because of the fear that oil may not be available in the near future. This was evident, when Saudi Arabia doubled its crude production after Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait – an increase that compensated for all the oil that the world lost from Kuwait and Iraq. Yet, prices increased above $30/bbl for a number of months. It also was evident at the beginning of the Gulf War, when oil prices did not decline following President George Bush’s release of oil from the U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR). Political problems in the oil-producing countries may cause a panic that will cancel out the effects of any crude output increases. Therefore, the price band’s ceiling will not hold. If people do believe that the band is effective, spot oil prices will fluctuate more than ever, and speculators will find that the price band provides a safe haven. Prices will either be around $20/bbl or $30/bbl. Speculators will sell when oil prices start declining, thus dragging prices to the band’s lower end. They also will buy when prices are low, and OPEC is set to cut production, forcing prices to increase toward the band’s upper limit. Because speculators know that OPEC will interfere only after 20 days of prices exceeding $28/bbl, they will hold on to their contracts until the end of that period; then they will get rid of them all at once. It appears that speculators will do OPEC’s dirty work on their own. In fact, this could be what happened toward the end of last March, when OPEC’s basket price declined below $22/bbl for a few days. OPEC watched while speculators bought more contracts and increased prices, believing that the producers would cut output to increase prices. It remains to be seen how long this game can go on. Will speculators panic if prices stay below $22/bbl for more than a month? More likely, yes, and prices will go even lower. Only then will we wonder what happened to the price band. The price band device has not worked, even when it was set by organizations that are more powerful than OPEC. These organizations include the International Bauxite Association (IBA), the International Coffee Organization (ICO), the International Tin Council (ITC) and the International Rubber Agreement (IRA). Some experts argue that the only organization that was successful in managing a price band was ITC. In 57 financial quarters between 1957 and 1977, ITC interfered in the market 30 times, to raise the price above the existing level. Studies show that ITC successfully defended the price floor on every occasion but one. However, critics say that ITC was defending a low price floor. Unlike OPEC, ITC consists of producers and consumers, thus making it easier to defend prices. It seems that ITC’s price band is set around a competitive price, with the upper and lower limits corrected for market failures. This is not the case with OPEC’s price band, because the competitive price is lower than the band’s lower end. Thus, OPEC is defending a band that is not sustainable in the long term. Market Share Considerations Another reason that a price band will not work is that it requires a large market share. OPEC’s share of the world oil market is relatively small. The group currently controls about 40% of global oil production – a market share that is not high enough to defend a price band. The table in this article shows OPEC’s oil production and market share for the years 1970 through 1999. As shown, OPEC’s market share never exceeded 56%, even at its "power peak," and it declined to as little as 30% in 1985. All other commodity organizations have a market share that is much larger. For instance, ICO controls more than 90% of the world’s coffee production. ITC controlled more than 90% when it was established, and when its market share declined to a low in 1933, it was still at a dominant 73% level. In 1978, the fifth ITA controlled 87% of world tin production. IBA also controlled 84.6% of the market economies’ bauxite production in 1976 and 72.7% of total world output for the same year. In 1984, IBA still controlled 73% of the global bauxite market. Even unsuccessful cartels, such as the International Copper Organization – with major producers such as Canada and the U.S. not included – controlled 70% of its commodity’s market, a share significantly larger than that of OPEC. Furthermore, a price band requires dividing the market among a cartel’s members. While OPEC has a quota system, it does not divide the market – one of the main requirements for a price band to succeed. In 1983, OPEC established a quota system, 23 years after the group’s establishment and 10 years after it claimed success as a "cartel." Even after 1983, members did not follow their quotas. Nevertheless, OPEC never divided the market, a move that helped the "Seven Sisters" major oil companies control the global market for an extended period after the Achnacarry agreement in 1928.

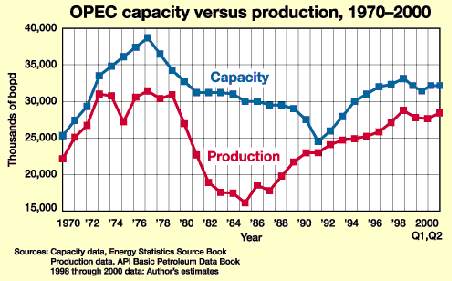

Violations / Violators A further liability to a price band is that it requires constant monitoring of a cartel’s quota system to identify violations and violators. OPEC lacks a monitoring system to oversee production and shipments. All other organizations and cartels that set price bands have consistent monitoring systems that belong to the organizations and not to the member-countries. ICO even hired an auditing company to monitor compliance. It requires all exporting members to issue certificates of origin for every shipment. In another example, IBA requires a "certificate of origin" for exportation. The diamond cartel has a special way of monitoring – it buys all the diamonds in the world from its producers. OPEC established a Ministerial Monitoring Committee 25 years after the group’s formation and several years after its claimed success as a cartel. However, this system is different from those developed by other organizations, and it monitors the market rather than oil shipments. A price band also requires the punishment of cheaters and quota violators by creating and implementing a punishment mechanism. One of the main characteristics of classical cartels is the existence and implementation of a punishment mechanism to deter members from cheating. OPEC has no such punishment mechanism, which raises the question about its ability to practice a price band. But other organizations do have punishment mechanisms. In ITC, for example, violations will lead to a reduced quota in the following quarter. Economists attributed the success of ITC’s price band to the "discipline shown by council members." In the ICO, cheating countries suffer a future quota reduction equal to the amount of the overshipment. Second and third overshipments have double deduction penalties. Punishment is even more severe in the diamond cartel, with De Beers acting as the cartel’s authority. De Beers uses buffer stocks to punish quota violators or members who want to leave the cartel by lowering the prices of their types of diamonds. This punishment was enacted against Zaire (now Democratic Republic of the Congo) in 1981, when that nation chose to market its production independently until it returned to the cartel. Some economists believe that Saudi Arabia increased its oil production in 1986 as a form of punishment. They also believe that the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait was another form of punishment. Although this could be true, the punishment did not come from OPEC acting as an organization. Cartel Above Country A price band requires that a cartel’s authority be paramount over individual members’ authorities. This is not the case for OPEC, where member governments retain production autonomy. Authority in other organizations is, indeed, above the member governments. For instance, ITC has the power to order a member country to lower its production to maintain a price floor. Not following these orders will result in punishment. De Beers signs exclusive long-term contracts with major producers to supply a certain proportion of De Beers’ annual sales. This system ensures that a reduction in the demand for diamonds will result in a reduction in production. Cash & Buffer Stocks A price band requires cash and buffer stocks to support prices, and to prevent high rates that lead to substitution and erosion of the cartel’s market. The objective of buffer stocks is to maintain prices within a range desired by the cartel. The cartel will collect and maintain a fund, and keep part of the commodity in stocks. When prices decline below the minimum price, the cartel authority uses the fund to buy the commodity on the open market and increase prices. When prices surpass the designated ceiling, the cartel sells some of its stocks to lower price and to prevent substitution. OPEC has never had a mechanism of this type; thus its price band is rendered defenseless. Although OPEC may not meet this criterion, one could argue that the existence of excess capacity in the major producing countries constitutes the "buffer stock," and that it has been used in the past many times to influence prices. Output and productive capacity of OPEC members between 1970 and 2000 can be seen in the accompanying chart. The difference between output and productive capacity is the excess capacity that exists mainly in three countries: Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates. Other OPEC members have produced at capacity most of the time. However, the main distinction between OPEC and other organizations is that buffer stocks in other groups are a part of the cartel agreement, and the cartel authority controls the buffer stock. OPEC’s excess capacity is controlled by individual countries – it is based on the interests of the countries, not the interests of OPEC. After the price slide of 1982 – 1983, Saudi Arabia and its Gulf allies took the burden of cutting production to stabilize prices, while other OPEC members increased their output. Those actions were taken unilaterally by the individual countries and not by OPEC authority. Many examples show that the Saudis – both alone and sometimes joined by the UAE and Kuwait – have used their excess capacity for their personal interest at the expense of OPEC as a whole. In fact, about 90% of the output cuts in 1973 that led to the group’s claimed success were made by only three countries: Saudi Arabia (approximately 60% of the cuts), Kuwait and Libya. Even if we believe that the excess capacity will work like buffer stocks, OPEC cannot manage a price band, because there is no excess capacity these days. The recent run-up in oil prices is our best evidence of that. Furthermore, a price band requires the voting system to be based on each member’s share. The vote in OPEC is by country, regardless of production rate and reserves. Other commodity organizations follow a different approach, where large producers officially have more power than small producers do. Votes are distributed, based on the amount of production or exports. In this case, the dominant producer(s) can keep the cartel in line. Quota Systems A price band requires a quota system that is based on tangible measures, such as production and export levels. OPEC’s quota system is based on current reserves and production capacity but not on current and previous production rates. Reserve and capacity figures are members’ own estimates, and there is no cartel-approved method to document them. This reinforces the looseness of OPEC’s quota system, because countries can inflate their reserves and production capacity to obtain a higher quota. The most crucial element in a cartel’s survival is accurate information. The existing information system prevents OPEC authorities from obtaining meaningful quota allocations. Other commodity cartels base their quotas on previous export levels that are tangible and monitored by the cartel authority through export licensing or other methods. Large Producer Roles A price band requires the largest producer in the organization to have a large market share. On a percentage basis, the market share of OPEC’s largest producer, Saudi Arabia, is much smaller than the market share of the largest producer in any other commodity organization. The highest market share attained by Saudi Arabia in the world oil market was 17% in 1981, and it eventually dropped to a mere 6% in 1985. Malaysia controls more than 40% of global rubber production. In 1995, Australia produced 39% of the world’s bauxite, while Saudi Arabia produced only 13% of the global oil output. Malaysia also controls more than 30% of the world’s tin production. In 1993, Brazil produced 30% of the world’s coffee, and the country also controls a large portion of the bauxite market. Export Dependence A price band requires OPEC’s members to limit their dependence on oil exports, so that these countries can maneuver to keep prices within the designated range. Most OPEC members are more dependent on their commodity (oil) as a source of income than are members of other commodity organizations. Brazil, Malaysia, Australia, Jamaica, Bolivia, Democratic Republic of the Congo, South Africa and Colombia are all countries that have extensive income sources other than those commodities tied to cartel-type organizations. All OPEC members, including Saudi Arabia, are highly dependent on oil revenues. More than 82% of Saudi exports are crude oil and related products, while other leading commodity producers depend less on their primary commodities. For instance, only 48.6% of Brazilian exports are primary commodities – these include coffee, bauxite and other commodities. Only 39.53% and 39.34% of the total exports of Malaysia and Jamaica, respectively, are represented by primary commodities. Therefore, other commodity organizations have larger, more diverse sources of income to fund buffer stock purchases when prices are low. Unlike other organizations, OPEC members’ bargaining power is limited, due to their heavy dependence on oil exports. In conclusion, the many points discussed in this article show that other

commodity organizations have more power than OPEC, yet they were not able to manage their markets through

price bands. One must wonder for how long OPEC officials will keep talking about this price band and how much

success can be attributed to good luck rather than actual ability to manage world oil markets. The most recent

increase in oil prices is the result of uncertainty and lack of excess capacity, not OPEC’s price band.

The latter was violated more than once, when OPEC’s basket price exceeded $28/bbl for more than 20 days

without any action from the organization. The price band will collapse, once oil producers increase their

capacities. The author

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dr.

A. F. Alhajji is a contributing editor for World Oil, as well as a research professor at Colorado

School of Mines. He joined the school’s staff in August 1997 as a visiting professor from the University

of Oklahoma, where he received his PhD in economics in 1995. Syrian by birth, Dr. Alhajji was exposed to the

petroleum industry’s intricacies at an early age and has more than 200 articles and columns to his

credit. In addition to World Oil, he contributes to several academic and international journals. He also is a

columnist for two newspapers and a weekly magazine in England and Saudi Arabia. Dr. Alhajji developed a

computer program to assist oil-producing countries in determining the economics of buying and selling oil in

today’s volatile market. He has received numerous awards, including the Teaching Excellence Award at

Colorado School of Mines. He currently is writing two books – one on OPEC and the world oil market, and

one on energy economics.

Dr.

A. F. Alhajji is a contributing editor for World Oil, as well as a research professor at Colorado

School of Mines. He joined the school’s staff in August 1997 as a visiting professor from the University

of Oklahoma, where he received his PhD in economics in 1995. Syrian by birth, Dr. Alhajji was exposed to the

petroleum industry’s intricacies at an early age and has more than 200 articles and columns to his

credit. In addition to World Oil, he contributes to several academic and international journals. He also is a

columnist for two newspapers and a weekly magazine in England and Saudi Arabia. Dr. Alhajji developed a

computer program to assist oil-producing countries in determining the economics of buying and selling oil in

today’s volatile market. He has received numerous awards, including the Teaching Excellence Award at

Colorado School of Mines. He currently is writing two books – one on OPEC and the world oil market, and

one on energy economics.