Oil and gas in the capitals

Robert Gordon’s recently published book, The Rise and Fall of American Growth, is the most discussed book in Washington, D.C. Dr. Gordon is an economist at Northwestern University. His thesis is that the incredible technological innovations of the 1870–1920 period were a “one time in history” event that cannot be replicated. Innovations, such as electricity, telephones, indoor plumbing, AC, cars, airplanes, radio, sanitation, refrigeration, antibiotics, etc., transformed the U.S. They were responsible for the extraordinary growth in U.S. (and world) GDP and incomes over the past 150 years—especially the “golden period” of 1945-1970. According to Gordon, no other similar, historical period has brought comparable progress, or is likely to again.

His controversial argument is that U.S. growth has been much slower since 1970, and will continue to be slow in the future. Thus, the U.S. should get used to productivity and growth rates of about 1% annually, instead of nearly 3%—a huge difference. Further, there is little that the government can do with monetary, fiscal, tax, or other policies to change this measurably.

This pessimistic message has profound economic and political implications. The firestorm of debate that Gordon has generated focuses on whether he is correct that the U.S. faces an inevitable future of anemic growth, or if the “techno-optimists” predicting a bountiful future are correct.

However, a critical issue is that nowhere in Gordon’s 762-page book does he give credit to oil and gas (O&G) for the economic miracle of the past 150 years. None of the innovations that he identifies would have been possible without massive amounts of energy. This is especially true of O&G, which powered the 20th century and will provide most of the world’s energy during the 21st century.

Gordon combined the historical UK/U.S. growth record with a forecast, and overlaid a curve showing growth increasing steadily to the mid-20th century, and then declining to 0.2% annually by 2100. He translated these growth rates into corresponding levels of per-capita income (2005 dollars), which, for the U.S., in 2007 was $44,800. The UK level in 1300 was $1,150, and it took five centuries for that to triple to $3,450 in 1800, and over a century to double to $6,350 in 1906, the transition year from UK to U.S. data. Even with the growth rate slowing after 1970, his forecast U.S. level for 2100 is $87,000, almost double that of 2007.

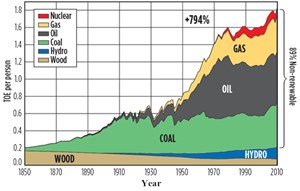

An essential implication of Gordon’s work, which, unfortunately, he does not recognize, is the absolutely essential role played by fossil fuels in this economic miracle, especially O&G over the past century, Fig. 1. Between 1850 and 2010, world population increased 5.5-fold; world energy consumption increased 50-fold; world per-capita energy consumption increased eight-fold; and nearly all of the world’s increase in energy consumption was comprised of fossil fuels.

Without the availability of adequate supplies of accessible, reliable and affordable O&G, little of the past two centuries’ economic progress would have been possible. This critical fact is lost in Washington’s firestorm of debate over Gordon’s work.

Notably, even with Gordon’s pessimistic assumption that economic growth will decrease to 0.2% annually by 2100, even modest economic growth will require large energy supply increases. O&G largely powered world economic growth over the past century. So, what energy sources are required to enable the world to continue to increase income, wealth, productivity and standards of living?

The International Energy Agency (IEA) forecasts that fossil fuels will meet most future energy needs. These fuels, which comprised 81% of the 2010 primary fuel mix, remain the dominant energy sources through 2040. Even greater O&G utilization may be required. EIA forecasts that 1 billion people will be without electricity, and 2.6 billion will lack clean cooking facilities in 2030.

In his concluding chapter, Gordon discusses several policies that may increase economic growth, including less regulation. Unfortunately, none of the regulatory reforms that he identifies deal with energy. He thus errs again in failing to recognize the threat that increasing, harmful energy regulations will have on future O&G production.

The bottom line is that world economic and technological progress over the past two centuries would have been impossible without the massive use of O&G. Further, vast, increased quantities of O&G will be required in the coming decades. The major threats to continued economic progress are policies and regulations that may inhibit O&G development. ![]()

- Applying ultra-deep LWD resistivity technology successfully in a SAGD operation (May 2019)

- Adoption of wireless intelligent completions advances (May 2019)

- Majors double down as takeaway crunch eases (April 2019)

- What’s new in well logging and formation evaluation (April 2019)

- Qualification of a 20,000-psi subsea BOP: A collaborative approach (February 2019)

- ConocoPhillips’ Greg Leveille sees rapid trajectory of technical advancement continuing (February 2019)