Regional Report: Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia is defined as the cluster of countries located geographically south of China, east of India, west of New Guinea and north of Australia. The region is one of the most densely populated areas in the world, with more than 600 million inhabitants. The region has experienced rapid economic growth, and energy demand has increased continuously in recent decades. Most of the countries in the region rely heavily on oil and gas as their primary source of energy. Oil and gas account for more than 60% of Malaysia’s energy consumption, and more than 50% for Indonesia.

Even though E&P activity started in Southeast Asia (SEA) at the beginning of the last century, the region’s oil and gas production is still considerably lower, compared to other major producing areas. To meet the area’s growing demand, operators need to expand their activity, to fully exploit the region’s energy-producing capabilities.

RESOURCES AND FUTURE POTENTIAL

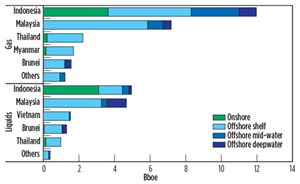

Reserve calculations show that the region is rich in oil and gas, with significant reserves yet to be exploited, Fig. 1. Estimated recoverable reserves are approximately 40 Bboe, with nearly 65% of the total resources being natural gas. Indonesia has the third-largest, estimated, recoverable natural gas reserves in Asia, ranked behind Turkmenistan and China. As of 2015, Indonesia dominated liquid and natural gas production, followed by Malaysia. The majority of the wells are located offshore.

POSITION OF REGIONAL PRODUCTION

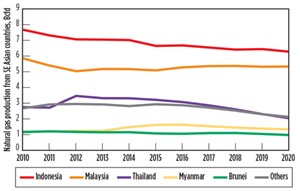

Although domestic demand has increased exponentially, SEA is still an important gas producer and LNG exporter, Fig. 2. According to 2014 U.S. EIA figures, Malaysia is the world’s second-largest LNG exporter, and the second-ranking natural gas producer in the region. Indonesia is the world’s fifth-largest LNG exporter after Qatar, Malaysia, Australia and Nigeria. Thailand is the third-largest natural gas producer, but it is a net gas importer, due to its rapidly growing domestic demand.

Myanmar was the region’s fourth-largest gas producer, with most of its production exported to Thailand and China. Brunei also relies heavily on its hydrocarbon revenues, and is an important LNG exporter in this region. During 2015, Southeast Asia’s natural gas production is estimated at approximately 21 Bcfd. Rystad Energy projects that production will decrease to 18 Bcfd by 2020. The natural decline curves of mature fields will be responsible for the majority of the reduction.

Indonesia holds the highest amount of recoverable liquid resources in SEA, totaling approximately 5 Bboe. Malaysia follows, with nearly 4.5 Bboe. Vietnam, Brunei and Thailand’s liquid resources are 1.5 Bboe, 1.0 Bboe and 900 MMboe, respectively. In most of the countries, the resources are located primarily in shallow waters. There is an expectation that Indonesia will have a large resource contribution from

onshore activity.

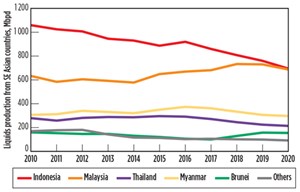

Total liquids production (Fig. 3) in the region was around 2.4 MMboed during 2015. It is expected to decline to 2.14 MMboed by 2020. This decline is driven mainly by reductions in output from Indonesia and Vietnam. Although Rystad Energy estimates that liquids production will increase in Malaysia and Brunei by 2020, these increases will not offset reductions from other major producing countries.

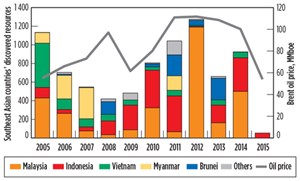

Historically high oil prices have driven, until recently, exploration activity in this area. Figure 4 shows historical discovered resources versus oil prices. Since 2010, most of the discoveries in this region have been made in Malaysia and Indonesia. In 2012, Kasawari field (~760 MMboe) was discovered with another four finds offshore Sarawak, in the prolific, central Luconia gas province.

Indonesia has several new fields with substantial resources, including Sanga Sanga field (~ 298 MMboe) in 2010, Kedung Keris field (~ 110 MMboe) in 2011, and Merakes field (~ 200 MMboe) in 2014. The main discoveries in Brunei have been Gerongong field (~ 220 million Boe) in 2011 and Keratau field (~ 150 million boe) in 2013. Yet, discovered resources in 2015 are at their lowest level since 2005.

E&P INVESTMENT OUTLOOK

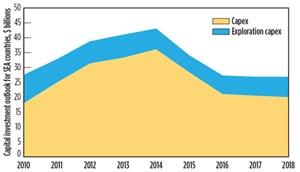

Considering the global oil market’s low prices, future capital investment in SEA’s upstream sector is expected to decrease. Figure 5 shows E&P investment from 2010 to 2018. In 2015, the countries that had the highest value in the area, in terms of capital investment, are Malaysia and Indonesia. The recent oil-price plunge has had a negative impact on the region’s capital investment. Spending has decreased from about $43 billion in 2014 to $34 billion in 2015, a 21% reduction from 2014 levels. Due to low oil prices, Rystad Energy estimates that capital investment will continue to fall in 2016, reaching $27.2 billion, which is about a 20% reduction from 2015’s level.

CONCLUSIONS

The future of SEA’s E&P market depends on a number of factors, such as commodity prices, government policies, economics, and technologies. Rystad Energy’s outlook is based on the current status of these factors. We anticipate that oil and gas production from SEA will decline in the near-future. This output reduction is due mainly to production declines in mature fields, and low investment in the upstream segment.

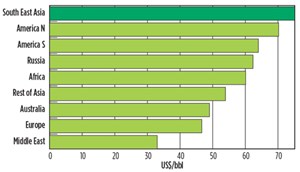

Most of this is because of low commodity prices. SEA countries have the highest average break-even oil price for non-sanctioned projects among other regions in the world, Fig. 6. Thus, new SEA projects are less attractive to E&P companies. In the past few years, we already have witnessed important, independent E&P companies, such as Hess Corp. and Newfield Exploration Co., exiting the SEA market.

Furthermore, as this region’s domestic energy demand increases, it might force the LNG exporting countries to import that commodity, so that they can meet their domestic demand while honoring long-term export contracts. As an example, we already have already seen Malaysia and Indonesia import LNG in recent years. In conclusion, SEA’s supply-and-demand imbalance is expected to worsen in the future. This will require local governments to implement policy changes that will attract and retain international E&P companies, while diversifying their energy sources to withstand the market supply downturn. ![]()

- Advancing offshore decarbonization through electrification of FPSOs (March 2024)

- What's new in production (February 2024)

- Subsea technology- Corrosion monitoring: From failure to success (February 2024)

- U.S. operators reduce activity as crude prices plunge (February 2024)

- U.S. producing gas wells increase despite low prices (February 2024)

- U.S. oil and natural gas production hits record highs (February 2024)