Regional Report: The Arctic

Seawater freezes at about 28.4°F. In the Arctic Circle, oil and gas operations start to freeze south of $50/bbl. Add a few rounds of sanctions and environmental politics, and the slush starts getting solid enough to lock up technology and capital.

Harsh conditions, high risk, and low return are not easy companions. In the Arctic, all three are landing on oil and gas activity like a ton of ice. The fast pace of past years has cooled off considerably, as many operators seek alliances or alternatives, or simply stop drilling. It’s not in cold storage yet; Arctic oil and gas operations continue with various exploration, development and infrastructure projects. But doing business in the Arctic has become even more challenging.

RUSSIA

Sanctions and prices bear down. Western sanctions and sliding oil prices are a double hit on Russian Arctic operations, and the country’s oil and gas activity in general. Roughly half of Russia’s budget revenue comes from oil and gas exports, so low prices are a problem for the energy sector and the overall economy.

The objective of the sanctions is to curtail Russian Arctic, deepwater and shale oil efforts by cutting them off from expertise and money, says the U.S. government. Those sanctions have come in waves since March 2014, after Russia annexed Crimea and used force in Ukraine.

Yuzhno-Kirinskoye. One of the most recent actions was taken in August 2015, with the U.S. adding Yuzhno-Kirinskoye field to its sanctions list. The field, in the Sea of Okhotsk, off the Siberian coast, was listed because of its huge, potential oil reserves.

The action means a license is required for exports, re-exports or transfers of oil from that location. A week earlier, the U.S. had added associates of a billionaire Russian gas trader; Crimean port operators; and former Ukrainian officials to the list.

The sanctions, which initially targeted individuals, soon banned the export of equipment and technology to companies, such as national oil giant Rosneft and independent gas producer Novatek. The sanctions also hit Russian lenders, cutting them off from long-term credit, and preventing relations with Russia’s Sberbank and VTB Bank.

In this environment, Russia, not surprisingly, is looking elsewhere for capital and expertise. While tough, the sanctions are not impermeable. Compliance is mandatory for U.S. and EU citizens and companies, but it is not for their international

subsidiaries. Still, the sanctions are having an impact in the Arctic, where technology and cash are in high demand.

Kara Sea. In January, Rosneft said sanctions would delay the oil giant’s 2015 Arctic drilling agenda. In the Kara Sea, where oil was discovered recently, the sanctions curtailed Russia’s joint, $700-million exploration project with Exxon Mobil. Kara Sea reserves are estimated at $900 billion and are being compared to Saudi Arabia.

“There will be no drilling in 2015. There is no platform, and it is too late to get one. The project was initially created for Exxon’s platform,” a Rosneft source told Reuters. Rosneft plans to resume drilling in 2016, but it expects commercial production to be delayed beyond 2020.

Prirazlomnoye. In September, Gazprom Neft began production from its second well in Russia’s only operating, offshore Arctic field, Prirazlomnoye, in the Pechora Sea. Production this year was expected to more than double 2014’s level of 300,000 tonnes. The program calls for 19 production wells, 16 re-injection wells and one absorption well, all drilled from the field’s zero emissions platform—the only stationary production platform in the Arctic.

In April, the Kirill Lavrov tanker delivered its sixth shipment of Prirazlomnoye oil to Europe. The Kirill Lavrov and Mikhail Ulyanov Arc6 class, double-hulled, icebreaking oil tankers are specifically designed for year-round oil transport from the platform.

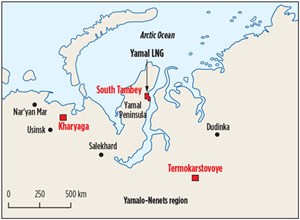

Yamal Peninsula. Off the Yamal Peninsula, Gazprom Neft made its first winter shipment of oil from Novy Port (Novoportovskoye) field. Located above the Arctic Circle, Novy Port is one of the largest oil and gas condensate fields being developed on the Yamal Peninsula. A 100-km pipeline transports oil to the coast, and a second pipeline, which is under construction, will provide capacity for 5.5 MMt of oil per year.

However, sanctions are likely to put a chill on development. The U.S. Export-Import Bank halted shipping of gas from Yamal, catching the project in mid-stride, with 22 wells drilled, and a runway and harbor built for the $27-billion undertaking by Total, OAO Novatek and China National Petroleum Corp.

UNITED STATES

Shell is in… and out. Amid much hullabaloo, Shell this year began and ended its return to the Chukchi Sea. Along the way, its rig was boarded by environmental activists and surrounded by kayakers. On location in August, drilling by Transocean’s Polar Pioneer semisubmersible was delayed to accommodate gale force winds and 11-ft seas.

The saga ended in late September when Shell, the company that discovered oil in the area in 1986, and the first explorer to return in three decades, called it quits. Shell drilled the Burger J well to a TD of 6,800 ft in the largely unexplored area.

Shows of oil and gas were found, but they were not enough to warrant further efforts, and the well will be plugged and abandoned. Further, Shell will stop exploration activity offshore Alaska.

“The Shell Alaska team has operated safely and exceptionally well in every aspect of this year’s exploration program,” said Marvin Odum, director of Shell Upstream Americas. “Shell continues to see important exploration potential in the basin, and the area is likely to ultimately be of strategic importance to Alaska and the U.S. However, this is a clearly disappointing exploration outcome for this part of the basin.”

This decision reflects the Burger J well result, the high costs associated with the project, and the challenging and unpredictable federal regulatory environment offshore Alaska.

Observed the authors of an article by Bloomberg, “The inglorious end to Royal Dutch Shell Plc’s $7-billion search for oil in Alaska means billions of barrels of crude will probably remain locked away in Arctic waters from the U.S. to Russia—at least as long as prices remain near $50/bbl.”

The Alaska LNG project, which would move product from the North Slope, marked a significant milestone in May with DOE’s conditional authorization to export LNG to non-Free Trade Agreement countries. The step follows a 2014 authorization to export to nations that have existing free trade agreements with the U.S.

The full application proposes to export up to 20 million metric tons per year of LNG from Alaska for a 30-year period. The project began in May 2014, with the signing of Senate Bill 138 to empower Alaska to become an owner in the project. In addition to the State of Alaska, participants include BP, ConocoPhillips, Exxon Mobil and TransCanada.

The Alaska LNG project includes a natural gas liquefaction plant and storage facilities; an export terminal at Nikiski on the Kenai Peninsula; an 800-mi gas pipeline from south-central Alaska to the North Slope; a gas treatment plant; and transmission lines connecting the project to gas producing fields.

The preliminary front-end engineering and design (FEED), with a $500-million budget, is due in early 2016. The pre-FEED will narrow the project cost estimate of $45 billion to $65 billion.

BARENTS SEA

Market hits. Oil prices are the bane of Norwegian exploration and development. After a year in which production increased for the first time in over a decade, the arrival of 2015 brought dire warnings of cuts in exploration and development spending.

Norway remained very active in 2014, with 56 exploration wells drilled, resulting in 22 new discoveries—two more than during 2013, according to the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate (NPD). Eight were in the North Sea, five in the Norwegian Sea, and nine in the Barents Sea.

This year, the NPD expected oil exploration in Norway’s Arctic waters would drop by half, as falling crude prices led state-controlled Statoil to stop its Barents Sea drilling. The directorate said companies planned to drill, at most, seven exploration wells in the Barents Sea, down from a record 13 in 2014. However, seven new wells in the Barents Sea would be more than the average 5.6 per year in the past decade, based on NPD figures.

The NPD reports steady interest in Awards in Predefined Areas (APAs) 2015 licensing. At the deadline for applying for APAs on the Norwegian Continental Shelf, applications had been received from 43 companies—about the same level as last year. Interest is greatest in the Norwegian Sea, but there is also an increase in the Barents Sea. APA 2015 was announced in April 2015, and the awards are scheduled for early 2016.

During APA 2014, the authorities received applications from 47 companies, for an available acreage area of 109,205 km2. At the September 2015 application deadline, it was possible to apply for a total of 127,608 km2. Since APA 2014, the APA areas have increased by 35 blocks in the Norwegian Sea and 11 blocks in the Barents Sea.

Statoil stops. Statoil’s activity is taking some hard hits from low prices, and the firm is actively looking for new partners and new solutions. The leader in Arctic activity drilled nine of 13 wells in the Barents Sea last year; in January, it announced that it would drill zero wells in 2015.

Statoil’s high-profile exploration in the Barents Sea Hoop and Johan Castberg areas had limited success last year. The company’s 2013-2014 exploration program hit an all-time high, with 10% of all exploration wells drilled since the beginning in 1980. But the company made fewer commercial discoveries than it hoped for.

Irene Rummelhoff, senior V.P. for exploration on the Norwegian Continental Shelf, put the results in context, explaining that, “Exploring in the Barents Sea is not a sprint, but a marathon. It is about long-term thinking, stamina and systematic building of knowledge.”

In 2015, she said the focus would be on analyzing the extensive data collected, interpreting the 3D data from the joint seismic acquisition in the southeastern Barents Sea and deciding on the way forward.

Terminating the terminal. In January, Lundin Petroleum and Statoil ended short-lived talks on jointly building an oil terminal in Norway’s arctic. The project was aimed at creating a hub for Barents Sea fields.

Ashley Heppenstall, CEO of Stockholm-based Lundin, said that the company’s Alta and Gohta discoveries are not close enough to Statoil’s Johan Castberg deposits to warrant joint development, and investment is too uncertain.

“Any discussions with Statoil, from our perspective, are difficult at this stage, because we can’t really help them,” Heppenstall told Bloomberg. “We need to do more drilling on Alta and Gohta, and to first of all understand how much we have.”

Early in 2015, Statoil faced continuing delays to its Johan Castberg Arctic waters project, due to disappointing exploration results, low oil prices, rising costs and a tax increase. At the time, Brent crude had dropped from $115/bbl to less than $52/bbl, prompting oil companies to reconsider projects around the globe. Statoil said Castberg is still profitable at prices below $80/bbl, but Rystad Energy AS, an Oslo-based industry consultant, puts the figure at $60/bbl to $70/bbl.

To build a terminal, says Statoil, it must get larger volumes from the Barents Sea, or have other partners contribute to the investment in, and operation of, the terminal. The Johan Castberg deposits hold between 450 MMbbl and 650 MMbbl of oil, while Alta is estimated to hold between 85 MMbbl and 310 MMbbl of crude. Gohta holds 60 MMbbl to 145 MMbbl of oil.

Barents collaboration. Bent on improving Barents Sea prospects, Statoil, Eni Norge, Lundin Norway, OMV and GDF SUEZ announced in June that they would collaborate on Barents Sea operations. Their Barents Sea Exploration Collaboration (BaSEC) will start as a three-year initiative led by Statoil. The objective is to find common answers for Barents Sea operations, through the sharing of data, cost-effective solutions, and more collaboration and coordination.

Polarled pipeline. A positive in the Norwegian arctic is the Polarled gas pipeline. In August, the pipeline crossed 66 degrees and 33 minutes north of the equator, making it the first Norwegian gas infrastructure to run across the Arctic Circle. It will transport gas from the Norwegian Sea to Europe.

The 36-in. pipeline runs from Nyhamna, in western Norway, to Aasta Hansteen field, in the Norwegian Sea, over a distance of 482 km. The Allseas Solitaire pipelaying vessel, the world’s largest, was used to advance the pipeline. The Polarled is reportedly the deepest pipeline on the NCS, in 1,260 m of water, and the deepest 36-in. line in the world. According to Statoil, the final piece of pipe was laid at Aasta Hansteen field on Sept. 28. ![]()

- Advancing offshore decarbonization through electrification of FPSOs (March 2024)

- The reserves replacement dilemma: Can intelligent digital technologies fill the supply gap? (March 2024)

- What's new in production (February 2024)

- Subsea technology- Corrosion monitoring: From failure to success (February 2024)

- U.S. operators reduce activity as crude prices plunge (February 2024)

- U.S. producing gas wells increase despite low prices (February 2024)