Regional Report: China

Despite being the world’s largest economy, the United States doesn’t have an official national energy strategy. The country relies primarily on the actions of private companies in the free market, with some government incentives and regulation. The private sector has done a good job of meeting U.S. energy demand. In contrast, China, though capitalist in many respects, has a government-directed energy strategy, influenced by its history, politics, geography and the requirements of a huge, fast-growing economy.

MAJOR IMPORTER AND PRODUCER

China is now the largest oil importer and the fifth-largest oil producer. It will account for a quarter of global oil consumption in 2015, so its actions will have a significant impact on the world’s oil and gas industry.

Understanding the growing importance of energy to its economy, the Chinese government launched the National Energy Administration (NEA) in 2008, to consolidate energy policies among the various agencies under China’s State Council, and to assess major energy issues. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), China’s new governmental leaders are streamlining various ministries related to energy and environmental protection, while expanding NEA’s responsibilities.

Keep in mind that coal remains China’s largest energy source, and the country is the world’s biggest producer and consumer of coal. The New York Times reported in November 2015 that China has been consuming 17% more coal per year than its government had previously reported; the revised total was 4.2 Bmt in 2013. While the Chinese government is committed to reducing coal’s share in its energy mix to reduce carbon emissions, use of this fuel will likely continue to grow with the economy.

THREE NOCs

China’s oil and gas sector is controlled largely by three energy companies that are owned primarily by the state: Chinese

National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), the China Petroleum and Chemical Corporation (Sinopec), and the China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC). When these companies were formed initially, they were entirely state-owned, were given responsibility over distinct portions of the industry, and did not compete.

Since the late 1990s, CNPC and Sinopec have swapped assets, so that they are now competitive, integrated companies, and CNOOC has entered the downstream sector. International oil companies also have been granted production sharing agreements offshore China, in Bohai Bay and the South China Sea, with CNOOC as the majority partner. In addition, both CNPC (with its subsidiary, PetroChina) and CNOOC (with CNOOC, Ltd.) have established publically traded companies, of which about 30% is owned by private investors.

“MERCANTILE” STRATEGY

The Chinese energy strategy is described, in detail, in a collection of essays in China’s Energy Strategy, the Impact in Beijing’s Maritime Policies, published by the China Maritime Studies Institute and the Naval Institute Press. Although published in 2008, the volume presents a strategic framework that probably still guides China’s energy planners today.

According to the Naval Institute scholars, China believes that markets are essentially anarchic, and that the country must strive to be energy self-sufficient by any means. Domestic resources must be developed and exploited to the fullest extent. Energy investments overseas should secure equity resources, so that China owns production that can be shipped back to domestic industries, Fig. 1.

China also has strived to reduce its dependence on the Middle East by buying open-market crude and LNG from a broader range of suppliers. China’s sea lanes and offshore territorial claims must be protected, and as a safeguard against supply disruption, pipelines should be used to import as much oil and gas as possible. China has established a strategic petroleum reserve, with 180 MMbbl of a planned 500 MMbbl of oil already in storage. And, in keeping with a mercantile view, crude oil imports are preferred over products, to protect the domestic refining industry.

OIL PRODUCTION

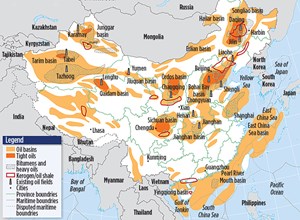

Through significant investment and application of technology, China lifted 4.6 MMbopd in 2014, 50% higher than in 1994. Some 80% of that crude was produced onshore, and 20% came from shallow offshore fields, according to EIA, Fig. 2. Despite extensive EOR onshore (including water, polymer and steam flooding), plus exploration offshore and in the western and central provinces, crude production has been flat since 2010.

Daqing field, historically one of the country’s most prolific onshore fields, is an example of China’s struggle to maintain production levels. In 2002, PetroChina drilled 1,975 development wells in the field in northeastern China, and produced 1.1 MMbopd. In 2014, PetroChina drilled 4,498 wells in the field, but produced only 792,000 bopd, a 27% decline in 12 years, according to analyst Gabriel Collins, in The Diplomat magazine. In late 2014, CNPC announced that it would manage the decline of the field’s production, by a further 20%, to 640,000 bopd in 2020.

Collins says that four factors restrain Chinese oil production. First, low oil prices make EOR techniques in older fields uneconomic. EIA also noted that CNOOC, CNPC and Sinopec cut 2015 E&P spending by 30%, 10% and 12%, respectively.

Second, petroleum geology in China is problematic. It’s difficult to wring more production from older fields, and the formations in potential plays are complex. Collins’s third factor is related specifically to the geology of the shale plays which, according to the U.S. EIA, contain 1,115 Tcf of technically recoverable gas and substantial amounts of tight oil. China’s shale plays are more complex, intermittent and ductile than those in North America, making them much more difficult to develop. One bright spot is Changqing field in northwestern China’s Ordos basin, where production peaked at 500,000 bopd in 2014, but has tapered off, possibly due to decreased drilling in 2015.

The structure of China’s domestic industry is the fourth factor limiting oil production growth, according to Collins. Large state companies like CNPC and Sinopec are not likely to duplicate the entrepreneurial successes of U.S. independents. Considering these four factors, Collins suggests that China’s onshore oil production may have reached its peak in 2015.

China’s onshore activity has been characterized by widespread use of advanced EOR methods. Steam and polymer flooding in northeastern China’s Liaohe heavy oil field enabled steady production of 200,000 bpd from 2009 through 2014. In Jilin field, also in the northeast, CNPC has combined hydraulic fracturing with CO2 injection to stem production declines. New EOR technology in Fengcheng heavy oil field also has helped to sustain production.

Better drilling and completion techniques, along with investment in infrastructure, have enabled production of about 400,000 bopd from Junggar, Tarim and other fields in the Xingjiand areas in the northwest, according to EIA. In July 2015, the Chinese government announced that it would open up six oil and gas blocks in the Xingjiang region for exploration by private companies to “stir up market vigor.”

China’s offshore fields have been open to participation from IOCs since the 1990s. Companies like ConocoPhillips, Shell, Chevron, BP, BG, Husky, Eni and Anadarko have provided capital and technical expertise for a share of production.

Bohai Bay accounts for most of China’s offshore oil production, with 404,000 bpd in 2014. Penglai field, operated by Conoco Phillips with CNOOC, has China’s largest FPSO, with a capacity of 190,000 bopd. In 2007, CNOOC projected that new developments would bring on an additional 200,000 bopd from Bohai Bay, but results have been disappointing. According to EIA, CNOOC added just 35,000 bopd by 2014 from five discoveries, and reported additions of about 90,000 bopd from several smaller fields in 2015. These additions are probably not sufficient to offset the natural 4% decline in Bohai’s field production, concludes analyst Collins.

CNOOC also has made oil discoveries in the gas-prone South China Sea. In 2014, these fields, primarily in the Pearl River Mouth basin, produced 222,000 bopd. Discoveries in five blocks of the eastern South China Sea are expected to achieve peak production of around 140,000 bopd in the next few years. CNOOC’s most recent licensing round, issued in 2014, included 33 blocks in Bohai Bay, and the South and East China Seas.

ONSHORE NATURAL GAS

China has 164 Tcf of proved natural gas reserves, which is the most in the Asia Pacific region. The country has worked to more than triple production, from 1.3 Tcf in 2003 to 4.4 Tcf in 2014. The Chinese government has set a production goal of 6.5 Tcf by 2020, taking away share from coal in the energy mix, along with LNG and pipeline imports.

Conventional onshore gas production is concentrated in the western and central regions. Large sour-gas discoveries in Yuanba and Puguang fields of the Sichuan basin will bring total gas production from these fields to 470 Bcf by 2016. Also in the Sichuan basin, Chevron is building two sour gas processing plants in the Chuangdongbei basin, to handle 204 Bcf/year from fields that were expected to come online in 2015.

In the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region in the northwest, the Tarim basin feeds 832 Bcf/year into two pipelines to Shanghai, Beijing and Guangdong. Exploration continues in the Tarim basin, and CNPC has made promising discoveries in the Junggar and Qaidam basins, in Xinjiang and Qinghai provinces, respectively.

In the northeast, with technical assistance from Total and Shell, CNPC has developed tight gas in the Changqiing basin’s Sulige and Changebei fields. Combined production reached 1,347 Bcf in 2014, contributing 31% of China’s gas output.

NATURAL AND UNCONVENTIONAL GAS

The South China Sea (SCS) has been the primary target for offshore gas exploration and development; CNOOC produced 175 Bcf in the SCS during 2014. Yacheng 13-1 field in the western SCS has supplied gas to fuel Hong Kong’s power generation. As this field’s production has declined, CNOOC has developed nearby blocks in the Pearl River Mouth and Qiongdongnan basins. In 2014, CNOOC made two significant gas discoveries in the Qiongdongnan basin, including Lingshui 17-2, with estimated proved reserves of 3.5 Tcf.

Husky Energy recently began production from the Liwan 3-1 deepwater field in the eastern SCS. With further development on adjacent fields, total production is expected to ramp up to 180 Bcf/year by 2018. Five other IOCs have PSAs in the SCS.

China has also begun to develop unconventional resources, including shale gas and coalbed methane. China’s most promising shale gas resources are in the Sichuan and Tarim basins, and are still in the nascent stages of development. Production from CNPC’s Changning-Weiyuan Block in the Sichuan basin increased five-fold from 8.2 Bcf in 2013 to 46 Bcf in 2014. Sinopec expects its Fuling field to reach 353 Bcf/year by 2017.

Despite these successes, progress has been slow in developing shale gas resources, due to complex geology, a shortage of water and lack of technical expertise. Thus, the government has reduced its 2020 gas production target to about 1.06 Tcf from twice that amount. CNPC is working with Shell, and Sinopec has projects with Chevron and ConocoPhillips to share technology and production. Chinese NOCs also have partnered in North American shale gas projects to build knowledge.

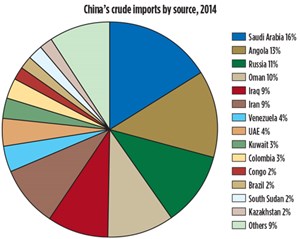

BUYING EQUITY RESERVES

Since 1993, China has been a net importer of oil, and has sourced most of its crude from the Middle East. After the two invasions of Iraq by the U.S., China recognized that Middle Eastern supplies were vulnerable to disruption, and began implementing a strategy to diversify its crude oil supply chain. Still, in 2014, 51% of its 6.2 MMbpd of oil imports came from Persian Gulf countries, Fig. 3.

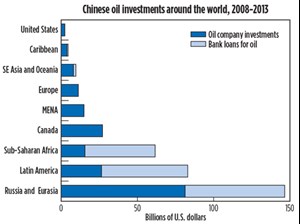

Since 2008, China has implemented a strategy of purchasing “equity reserves” in 42 countries, in the Middle East, North America, Latin America and Asia. By obtaining ownership of these reserves, China can take production without competition on the open market. The International Energy Agency reported that, combined, CNPC and CNOOC made $73 billion in equity investments from 2011 to 2013. In addition, China has made bilateral oil-for-loan agreements, worth nearly $150 billion, with eight countries.

CNPC, CNOOC and Sinopec have all invested in large Iraqi fields, which contributed 9% of total oil imports in 2014. Other recent direct equity acquisitions have included shares of deepwater fields off Brazil and West Africa, natural gas and CBM production in Australia (which feeds LNG trains for export), oil sands in Canada, and shale gas projects in North America.

NO POLITICAL CONDITIONS

China makes its loans and investments without political conditions, and has been criticized by the U.S. for its economic support to rogue states like Iran, Sudan and Myanmar. Iran’s share of Chinese crude imports declined from 14% in 2005 to 9% in 2014, but the actual amount increased from 250,000 bopd to 560,000 bopd over the same period. Reuters reported that China has further increased its oil purchases from Iran, in response to the recent signing of the nuclear control agreement.

China’s investment in Sudan gave it a foothold in North Africa, and a steady supply of oil, while providing the regime with financial and political support. In 2012, the Darfur conflict interrupted production, and the Chinese military intervened to protect its assets in the country. As hostilities have waned, and production has resumed, South Sudan contributed 2% of China’s oil imports in 2014.

PIPELINE IMPORTS

China also imports nearly 800,000 bopd from Russia and Central Asia, through pipelines from Eastern Siberia and Kazakhstan. China also imported 1.133 Tcf of natural gas in 2014 via pipelines from Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kasakhstan and Myanmar. A gas pipeline from Russia, scheduled to come online in 2018, will have the capacity to add 1.1 Bcf/year of imports.

THE MALACCA DILEMMA

According to Naval Institute scholars, Chinese leaders, instead of considering their country a confident Asian power, view themselves as a beleaguered underdog that must be prepared to defend itself against unpredictable aggressors. They consider Taiwan part of China, but also an island that could be a platform to defend the mainland. Recent construction of seven artificial islands in the Spratlys is meant to confirm what the Chinese believe to be their sovereignty over the entire South China Sea. Likewise, China’s placement of 14 platforms in the East China Sea, in waters also claimed by Japan, is as much a move to defend the homeland as it is to develop hydrocarbon resources.

In this context, the Strait of Malacca is significant from both economic and security perspectives. More than 80% of China’s oil imports pass through the strait. In addition, since they began in 2006, Chinese LNG imports have risen to 957 Bcf in 2014, and Chinese NOCs have contracts for 6.6 Bcf/day through 2030.

China has reduced the risk of gas supply disruptions with pipeline connections to its west, but nearly half of gas imports will be carried by LNG tankers through the Strait of Malacca and South China Sea. ![]()

- Advancing offshore decarbonization through electrification of FPSOs (March 2024)

- Shale technology: Bayesian variable pressure decline-curve analysis for shale gas wells (March 2024)

- What's new in production (February 2024)

- Subsea technology- Corrosion monitoring: From failure to success (February 2024)

- U.S. operators reduce activity as crude prices plunge (February 2024)

- U.S. producing gas wells increase despite low prices (February 2024)

- Applying ultra-deep LWD resistivity technology successfully in a SAGD operation (May 2019)

- Adoption of wireless intelligent completions advances (May 2019)

- Majors double down as takeaway crunch eases (April 2019)

- What’s new in well logging and formation evaluation (April 2019)

- Qualification of a 20,000-psi subsea BOP: A collaborative approach (February 2019)

- ConocoPhillips’ Greg Leveille sees rapid trajectory of technical advancement continuing (February 2019)