Why supermajors botched unconventionals

In Malcolm Gladwell’s interpretation of the David and Goliath story, Goliath, while immensely strong, is so blind that he must be led into battle by an attendant.

|

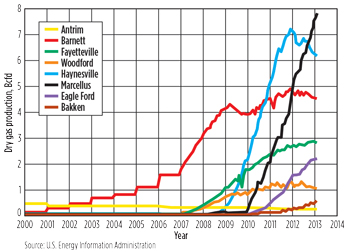

In Malcolm Gladwell’s interpretation of the David and Goliath story, Goliath, while immensely strong, is so blind that he must be led into battle by an attendant. Goliath cannot see well enough to find his opponents. Instead, Goliath calls out, “Choose you a man and let him come down to me!” Gladwell’s book, David and Goliath: Underdogs, Misfits, and the Art of Battling Giants, is “about what happens when ordinary people confront giants. … powerful opponents of all kinds. … Each chapter tells the story of a different person—famous or unknown, ordinary or brilliant—who has faced an outsized challenge and been forced to respond. Should I play by the rules or follow my own instincts?” Goliath’s business model was to be so large, strong and well-placed that the competition would have to come to him. The supermajors’ business model is similar. Opportunities, of sufficient size to be of interest to them, are too big for smaller companies to develop alone. That business model worked well for the majors in the 20th century and for their successors, the supermajors, at the beginning of the 21st century, but it failed when applied to unconventionals. Fast followers. The petroleum industry Goliaths assume that small companies must bring large, new discoveries to them. The presumption is that the little guys, e.g., the independents, can take the risks in new plays, but will need the deep pockets of a much larger company to develop a discovery. The Goliaths have adopted a strategy of being “fast followers,” with processes to screen opportunities and optimize development. For decades, this business model worked very well. Projects, with the scale to be of interest to giant companies, were too large for a small company, or even many countries, to fund and manage alone. Getting to first oil or gas in remote, harsh environments took immense capital investments. No petroleum can be produced in deep water without an expensive infrastructure that takes years to build. No gas can be produced in a remote location without an LNG plant or a long-distance pipeline. The little guys could scrape up enough money for exploration, but not development. They had to come to the Goliaths. The supermajors had stronger balance sheets and credit ratings than many countries. They focused on funding and managing multi-billion-dollar development projects. To maximize their rate of return, the Goliaths developed processes to select the best projects, to optimize their development, and to execute and manage them safely and efficiently. Under the 80/20 principle of focusing on the big assets, they divested less-lucrative, mature and small fields. But unconventionals in North America didn’t require large investments to get oil and gas to the market. Production from the Bakken shale swamped the oil transportation system before the big guys figured out what was going on, Fig. 1. Natural gas from the Barnett changed the game, while the Goliaths were working on projects to build terminals to import LNG. Some of the hot, new unconventional plays are on acreage divested by the Goliaths as they high-graded their portfolios.

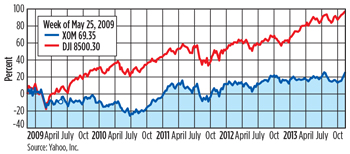

Chasing near-term growth. In his classic business book, The Innovator’s Dilemma, Clayton Christensen observed, “In good companies, resources and energy coalesce most readily behind proposals to attack, upmarket, into higher performance products that can earn higher margins. … The larger and more successful they become, the more difficult it is to muster the rationale for entering an emerging market in its early stages. … Small markets cannot satisfy the near-term growth requirements of big organizations.” When the Bakken, Eagle Ford and other unconventional plays were in their early stages, supermajors didn’t see them as competitive with their other opportunities. The unconventionals are downmarket plays that, by conventional metrics, do not appear to be sufficiently profitable or sustainable. Christensen did not provide oil industry examples in his work, but there are clear analogies between how the supermajors reacted to the unconventional plays and the examples that he provides in other industries. One of the reasons that the supermajors were willing to wait and watch the unconventionals develop in North America was that they assumed that, even if they failed to get into the play early, they would have an opportunity to buy a position. In 2009, Exxon Mobil entered into an agreement to acquire XTO for $41 billion in stock, which was approved in June 2010. Four years later, the deal is not looking good. Gas wells drilled by independents continued to come onstream, and the North American gas price declined. The XTO acquisition continues to be a drag on Exxon Mobil’s stock price, Fig. 2.

None of the other supermajors has done well in unconventionals in North America. In an interview with the Financial Times in October 2013, three months before his retirement, Shell CEO Peter Voser described the failure of his firm’s bet on U.S. shale gas as his biggest regret during his time with the company. The Goliaths have not been able to shrink their enormous footprints enough to be able to squeeze out an attractive profit margin from unconventionals. The situation seems analogous to Cinderella’s step sisters unsuccessfully trying to force their big feet into her tiny glass slipper. Warren Buffett took a different approach. Instead of buying into the production, he took a position in the infrastructure used to get Bakken oil to market—a railroad. At almost the same time that Exxon Mobil was purchasing XTO, Buffett bought the rest of BNSF Railroad for about $34 billion. Buffett’s purchase has been a big success. As in the California gold rush, those who supplied and serviced the miners were more likely to make money than the miners. Supermajors’ processes are optimized to be responsive to their existing major internal business units, which are focused on giant, high-volume fields that require huge capital investments and massive infrastructure. The processes that are at the core of the supermajors’ success with their traditional businesses can be a major impediment to success in the unconventionals. Inflexible processes. Processes are a two-edged sword, because, as Clayton Christensen noted, “Processes are meant not to change.” Processes drive consistency, and focus attention and resources on existing businesses. When a disruptive opportunity arises, processes can make it very difficult, if not impossible, for a process-driven organization to transition. Corporate processes for funding research default to being biased toward lower-risk, incremental development work on technologies with powerful internal constituencies. Funding tends to go to incremental improvements to well-established technologies that benefit the dominant business units. High-risk, potentially high-reward, untested ideas and technologies, including applications of technologies that are underutilized in the petroleum industry, are squeezed out of the budget or receive token funding. Individuals within the supermajors recognized the emerging opportunities of unconventionals, but processes dictated waiting to take a large stake when the trend was obvious. The old “wait, see, acquire” model has not worked as well as it does for conventional plays, because the supermajors’ processes are not well-adapted to running and developing unconventionals. Process-driven companies, operating in a fractal-like manner, strive to replicate processes throughout the organization on all scales. Attention is given to trying not to overwork the processes on the smaller scales, but the goal is to create consistency. The processes then become not just the company’s strength, but also it’s Achilles’ heel. While ensuring consistent performance, processes impede innovation and change. Slow technology adoption. The petroleum industry is infamous for being a slow adopter of technology. That can be the correct approach, when new technology without a track record for reliability is a critical part of a mega-project that is expensive and difficult to service or replace. The potential downside, due to uncertainty in the reliability of a new technology, can trump small improvements in performance Unfortunately, even when the upside greatly outweighs the downside, metrics for rewarding individual performance can make employees reluctant to take on any unnecessary risk. The cumulative result of each employee minimizing personal risk is to undermine the effectiveness of divisions of the company, including research and new business development, which should be embracing upside risk. Companies need to evaluate whether processes and metrics have created a culture in which the competitive edge has been blunted by risk avoidance. Minimal, individual risk-taking, as a reaction to a disruptive change, can create much higher risk for the organization as a whole. While the supermajors stumbled in unconventionals in North America, they still have their financial strength to play again in a big way. Shell has partnered with Gazprom to develop the Siberian Bazhenov formation, which is thought to be similar to the Bakken. Chevron has taken on significant unconventional political risk in signing with Argentina to develop the Vaca Muerta (Dead Cow) formation in Neuquén province. Chevron agreed to develop the acreage on which in 2010 Repsol-YPF discovered an estimated 16.2 billion bbl of oil and 308 TcF of gas. Repsol’s reward was to have their position nationalized in 2012. Hopefully, Chevron and Shell will also use their financial muscle to develop some cost-effective unconventional reservoir characterization technologies to compliment optimization of factory drilling. REFERENCES

|

- Applying ultra-deep LWD resistivity technology successfully in a SAGD operation (May 2019)

- Adoption of wireless intelligent completions advances (May 2019)

- Majors double down as takeaway crunch eases (April 2019)

- What’s new in well logging and formation evaluation (April 2019)

- Qualification of a 20,000-psi subsea BOP: A collaborative approach (February 2019)

- ConocoPhillips’ Greg Leveille sees rapid trajectory of technical advancement continuing (February 2019)