40 years later: Legacies of the 1973 oil crisis persist

On the 40th anniversary of the 1973 Arab oil crisis, the after-effects of the upheaval still linger in policies and attitudes across the global oil and gas industry.

JILL TENNANT

When President Richard Nixon lit America’s National Christmas Tree on Dec. 14, 1973, floodlights at the tree’s base illuminated its mostly energy-free ornaments. Balls and garland had replaced the thousands of twinkling light bulbs of the previous year. The tree stood as a stark, visible reminder of the oil crisis gripping many nations around the world at that time. TURBULENT TIMES October marks the 40th anniversary of the start of the Arab oil crisis. On Oct. 17, 1973, amid geopolitical unrest, an inflationary price environment and pre-existing oil and gas shortages, members of the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) initiated an oil embargo targeting the U.S. and The Netherlands, in response to their support for Israel during the Arab-Israeli War. The embargo list subsequently expanded to include Rhodesia, South Africa and Portugal.1

Because of the global nature of the crude oil market, the effects reverberated around the world. Global crude oil supplies immediately tightened, and prices rose sharply. Many consumers endured long lines, rationing and shortages at their local gasoline stations, Fig. 1. Although the embargo ended in 1974, the actions taken during that decade influenced energy views, policies and industries for future generations. The oil crisis focused attention on national energy security issues. Governments realized that the era of cheap, readily accessible oil was over. The risks associated with heavy dependence on foreign oil prompted many countries to reassess their energy policies. Some increased domestic production, while others diversified the global regions from which they obtained their crude supplies. Oil producing countries, such as Kuwait, Venezuela and Saudi Arabia, accelerated existing efforts to nationalize their oil industries, with many achieving complete nationalization by the late 1970s or early 1980s.2 To reduce overall energy usage, many countries instituted energy conservation initiatives, including improvement of operating efficiencies at their petroleum refineries, and developing more alternative energy sources. Some nations also implemented maximum national speed limits, in an attempt to decrease gasoline consumption, while others increased the mandated fuel economy standards for new vehicles. These efforts required bureaucracies and laws to manage them. For instance, the U.S. established a cabinet-level Department of Energy in 1977, to better coordinate its national energy issues and policies.3 Today’s oil and gas professionals, and investors, rely on the reports and forecasts of the International Energy Agency (IEA) when making financial and investment decisions. However, many people may not realize that the existence of the IEA is a result of the multinational efforts initiated in the wake of the oil crisis. In 1974, a group of oil-importing industrial nations formed the IEA as a cooperative body that could collectively respond to future oil disruptions. In addition to fostering cooperation and disseminating information, the IEA also established requirements for the storage and release of emergency oil reserves for net oil imports.

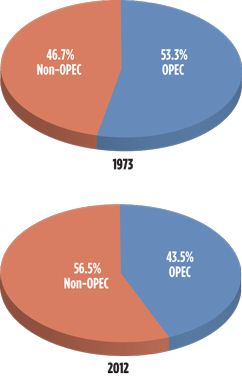

One very visible, immediate effect of the 1973 oil crisis was a large spike in the price of crude oil. The annual average spot price of Arabian Light crude oil nearly quadrupled from $2.83/bbl in 1973, to $10.41 in 1974.4 With OPEC controlling most of the world’s excess capacity, the embargo caused crude oil and gasoline shortages, Fig. 2. Today’s greater supply diversification helps minimize, but not eliminate, such extraordinary supply and price swings. Although OPEC remains a dominant force in the industry, its members only produced 43.5% of the world’s crude oil in 2012, compared to 53.3% in 1973, Fig. 3.5

Because of the IEA emergency oil stock requirements, member nations are now better equipped to respond to supply disruptions than they were in 1973. The IEA has coordinated global releases on three occasions: in anticipation of the Gulf War in 1991; after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005; and after Libyan oil disruptions in 2011.1 Individual member nations can also respond to their own domestic emergencies, after communicating the details and circumstances to the IEA. Fortunately, many IEA member nations substantially exceed the minimum requirement of crude oil and/or product equivalent to 90 days of the previous year’s average net oil imports. For instance, as of February 2013, the UK had 265, Korea had 216, and the U.S. had 174 days’ worth of reserve stocks, respectively.6 Sources of crude oil production have also changed over the last four decades. Many countries increased their domestic energy production through improved offshore drilling technology, investment in unconventional oil plays or exploration in more challenging environments. FOSSIL FUEL DEPENDENCE The 1973 oil crisis highlighted the need to conserve energy and expand alternative energy sources. Today, companies and citizens demand energy-efficient consumer products, processes and practices, without compromising performance or appearance. According to the U.S.’ National Park Service, the 1973 National Christmas Tree, with its energy-free ornaments, used 82% less energy than its 1972 counterpart.7 Four decades later, citizens have come to expect the best of both worlds. By the early 2000s, new LEDs (light-emitting diodes) on the National Christmas Tree enabled light displays that were both dazzling and energy-efficient. Fossil fuels still constitute 87% of the world’s energy consumption. Oil remains the predominant fuel, although its share of the total has declined for 12 consecutive years.4 Even the U.S., a primary target of the 1973 oil embargo, remains dependent upon fossil fuels to meet its domestic energy needs. While the majority of American energy still comes from fossil fuels, the use of alternative energy sources has, indeed, increased over the years. Fossil fuels were the source of just 78.6% of the nation’s energy production in 2012, as compared to 91.6% in 1973.5 Many people have little-to-no memory of the 1973 oil crisis, yet the actions of government officials, industry experts and ordinary citizens 40 years ago affect the lives of today’s oil and gas professionals and consumers, alike. People experience the legacy of this historic event first-hand, when a new car gets better gas mileage than its trade-in vehicle, a nation releases crude oil from its reserves, or an oil company utilizes IEA data to justify a new project. REFERENCES 1. International Energy Agency, “How does the IEA respond to major disruptions in the supply of oil?” www.iea.org/topics/energysecurity/respondingtomajorsupplydisruptions/, 2013.

|

- Applying ultra-deep LWD resistivity technology successfully in a SAGD operation (May 2019)

- Adoption of wireless intelligent completions advances (May 2019)

- Majors double down as takeaway crunch eases (April 2019)

- What’s new in well logging and formation evaluation (April 2019)

- Qualification of a 20,000-psi subsea BOP: A collaborative approach (February 2019)

- ConocoPhillips’ Greg Leveille sees rapid trajectory of technical advancement continuing (February 2019)