LYDIA THEVANAYAGAM, Deloitte’s Petroleum Services

|

| Anadarko Petroleum is mobilizing the Deepwater Millenium drillship to drill wildcat wells offshore Kenya (left). Meanwhile, Tullow Oil‘s Ngamia-1 onshore Kenya well has discovered light oil in multiple zones (center). Anadarko and Eni are planning to jointly develop the Mozambique LNG terminal. |

Limited historical exploration success and political instability in East Africa had led to a misconception that this region has limited oil and gas potential. Gas resources were found offshore in the 1970s, with not much more than oil shows onshore. Since 2006, independent African explorers began to pick up acreage, following which, they initiated the first serious exploration efforts in the region. Frontier exploration offshore East Africa has also commenced, with incredible successes. This article focuses on three countries in East Africa with evolving oil and gas activity: Kenya, Tanzania and Mozambique.

REGIONAL OVERVIEW

Exploration activity in East Africa over the decades has been minimal in comparison to the west coast, which has seen huge successes. Independent players have targeted exploration efforts in the East African Rift System (EARS), which has eastern and western arms running through Kenya, Tanzania and Mozambique, Fig. 1. Another target is the Turkana rift, which extends from Ethiopia into northern Kenya on the EARS western arm. Licensing activity has reflected the interest in Tanzania’s side of the Tanganyika rift basin and the Rukwa rift basin. Offshore exploration in Tanzania began in 2010, when Ophir Energy started its exploration campaign in the Tanzania coastal basin. Since then, the natural gas discoveries made offshore Tanzania have been significant. First exploration in the Rovuma basin began in 2010, offshore Mozambique. Exploration in the part of the Rovuma basin that falls in Tanzanian jurisdiction is also anticipated for the future.

|

| Fig. 1. East Africa onshore and offshore basins. |

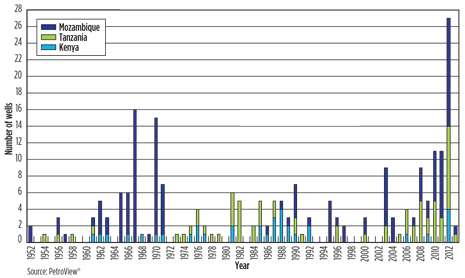

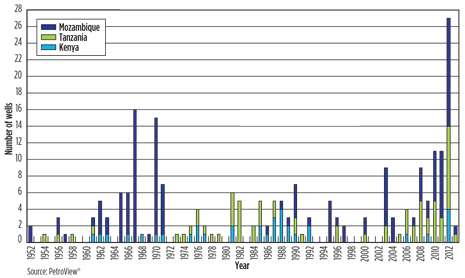

Figure 2 shows East Africa’s exploration record and, most significantly, how this has been transformed in the last few years. Despite the intense drilling activity seen in these countries, the region remains significantly underexplored. Prior to 2000, in the three focus countries, there were approximately 140 exploration, appraisal and stratigraphic wells drilled. In Nigeria, alone, over 3,000 wells had been drilled before the year 2000. With new entrants, new drilling activity will help de-risk the potential plays in the region, Table 1.

|

| Fig. 2. Exploration drilling surged in East Africa during the late 1960s and once again in 2012. |

| Table 1. Operators in Kenya, Tanzania and Mozambique, ranked by gross total acreage |

|

|

KENYA

Exploration history. Exploration in Kenya began in the 1960s with the participation of majors, such as Shell, BP, Chevron and Total. The National Oil Corporation of Kenya (NOCK), was incorporated in 1981. However, it wasn’t until 1992 that the country discovered small quantities of oil in the Loperot-1 well in the EAR basin. Following this discovery, there was a hiatus in exploration drilling, which lasted until 2006, when Woodside began its exploration campaign and spudded the Pomboo-1 well on offshore Block L-5. Pomboo-1 was Kenya’s first deepwater well, drilled in a water depth of 2,193 m. The well “failed to encounter hydrocarbons in the objective sandstone,” and was plugged and abandoned. Woodside delayed the drilling of their second well on the L-7 license, and subsequently, allowed its licenses to expire during 2008 and left Kenya. Following Pomboo, an onshore well, Bogal-1, was drilled by CNOOC in 2009. Bogal-1 encountered only gas shows, and CNOOC left the acreage. Exploration drilling in Kenya was restarted in 2012.

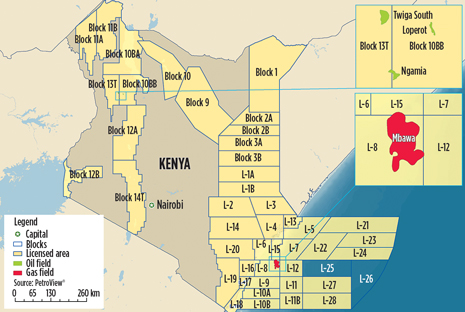

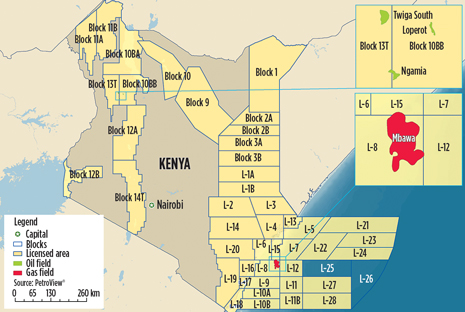

Licensing activity and key players. The number of open and awarded blocks has risen rapidly over the last few years. In Jan. 2007, 14 out of 24 blocks were awarded, with many of these being study licenses or technical evaluation agreements (TEAs). The difference in Kenya’s licenses today is striking, Fig. 3. During 2012, Kenya outlined eight new blocks extending offshore into the country’s deep waters. At the time of writing, Kenya has 46 blocks that have been demarcated and gazetted. Of these, 44 have been officially awarded; one block remains under application and one block was relinquished in 2012. Licenses in Kenya have traditionally been awarded through direct negotiation. However, taking into account the high interest in its acreage, NOCK has put forward a further eight blocks that will be made available in an auction-style licensing round.

|

| Fig. 3. Kenya’s current acreage and discoveries |

Recent exploration. During 2012, Kenya drilled five wells, including the first well offshore since Pomboo-1 in 2006.Ngamia-1 was the first well to be drilled on onshore Block 10BB by Tullow Oil, and its partner, Africa Oil. The well was spudded in the South Lokichar basin and discovered light oil in multiple zones. In August 2012, Apache began drilling its Mbawa-1 well offshore. The well was drilled in 864 m of water and discovered gas in its shallowest objective. The well encountered about 52 m of net gas in Cretaceous sandstones, but it failed to discover hydrocarbons in its secondary, deeper objective.

Tullow spudded the third well, Twiga South-1, onshore on Block 13T, directly west of Block 10BB. The well was announced as an oil discovery, the second in the South Lokichar basin, after encountering 30 m of net oil pay with hydrocarbon shows over a gross interval of 796 m. Tullow also drilled the fourth well, Paipai-1 in the Anza basin. Located on Block 10A, Paipai discovered “light hydrocarbon shows…while drilling a 55-m thick gross sandstone interval.” The well was suspended in March 2013, pending further evaluation. Offshore, Anadarko completed the drilling of its Kubwa wildcat offshore on Block L-7, which encountered non-commercial oil shows in reservoir quality sands.

Future plans. During 2013, a record number of exploration wells is planned, both onshore and offshore, as operators are reaching the end of their first phase of exploration which, in most cases, requires a well commitment. Following the Kubwa well, Anadarko is mobilizing the Deepwater Millenium rig to Block 11B, south of Block L-7, to drill the Kiboko prospect. Both of these wells have the objective of discovering oil.

Tullow, which has the largest operated acreage in Kenya, has an E&A program consisting of up to 13 wells. Following the drilling of Paipai, it is expected to spud the Etuko prospect on Block 10BB onshore. The Ekales prospect (formally known as Kongoni) is planned to be drilled during the year. Africa Oil also plans to spud a well on Block 9, which it operates. This will be the first well on the block since CNOOC’s failed Bogal-1 well in 2009. Next on Africa Oil’s drilling agenda is the Bahasi prospect during second-half 2013. BG Group, which operates Blocks L-10A and L-10B, aims to drill a well by the end of 2013. FAR Ltd, which operates block L-6, is seeking a farm-in partner to assist with a well this year. Ophir Energy has a well planned for 2014.

TANZANIA

Exploration history. In 1952, exploration activity began in Tanzania when BP-Shell Development Company was awarded acreage on the Tanzanian coast. The consortium drilled over 100 shallow-water boreholes, and first frontier wells, such as Mafia-1 (1954) and Zanzibar-1(1956) and Pemba-1 (1961), off coastal islands with little success. The Tanzanian Petroleum Development Company (TPDC) was incorporated in 1969 and signed its first PSA with Agip Africa. Agip acquired regional seismic data and began a five-well drilling campaign, which included the discovery of Songo-Songo in 1974. High commodity prices in the 1980s had an effect of increased exploration activity. Despite the gas discoveries of Songo-Songo and, later, Mnazi Bay (1982), Agip relinquished its interest in 1982. Several major players, including Amoco, Texaco and Esso, conducted exploration during the 1980s. However, these companies exited Tanzania following little exploration success, and upstream activity in the country slowed.

Smaller IOCs began to enter the country during the 1990s, acquiring licenses predominantly in coastal areas. In 2000, the first deepwater licensing round for acreage was held after the acquisition of additional geophysical data.

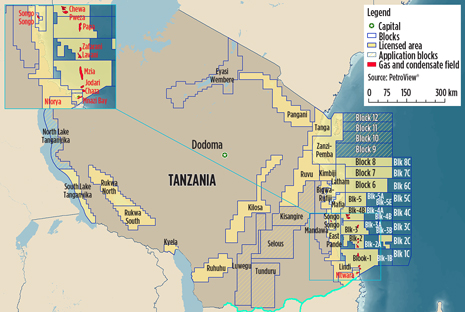

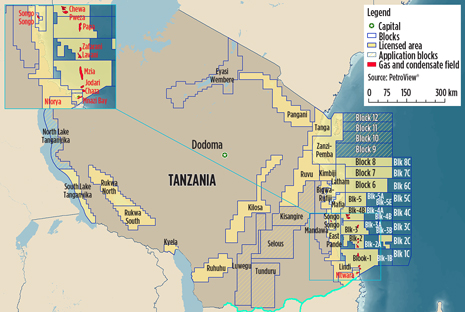

Licensing activity and key players. Offshore acreage is awarded in Tanzania through official licensing rounds, of which three have been held to date, Fig. 4. The latest was a mini-licensing round, during which the onshore North Lake Tanganyika acreage was on offer. TPDC has been preparing to launch a fourth deepwater licensing round, which will offer part-relinquished areas from current blocks and new deeper-water licenses. This licensing round is expected during 2013, following implementation of the new Natural Gas Policy. Eight blocks will be available, including the North Lake Tauganyika block onshore and additional seven blocks offshore, in water depths ranging between 2,000 and 3,000 m.

|

| Fig. 4. Tanzania acreage and gas discoveries |

Onshore acreage in Tanzania is traditionally acquired through direct negotiation with the government and TPDC. Over recent years, the award of onshore acreage has been rapid, with six of eight currently licensed blocks awarded since 2011. Heritage Oil was awarded 100% interest in the Rukwa North and Rukwa South Blocks in Nov. 2011, and also the Kyela license in Jan. 2012. In Feb. 2012, Swala Energy and partner Otto Energy were awarded two blocks, Pangani and Kilosa. Most recently, Jacka ratified a PSC over the Ruhuhu permit in March 2013.

Recent exploration. Interest in Tanzania peaked in 2010, when Ophir Energy partnered with BG group in May and began its three-well drilling campaign. The consortium contracted the semi-submersible Deepsea Stavanger for a drilling program, which commenced in October 2010 with the Pweza-1 well. This was the first deepwater well offshore Tanzania, drilled in 1,140 m of water. Pweza was announced as a gas discovery after encountering “a thick section of gas-bearing sands, which demonstrates the presence of a working hydrocarbon system.” Ophir followed this with another gas discovery on the Chewa prospect northwest of Pweza. Chewa encountered a 262-ft gas column. Ophir and BG’s third well, Chaza-1, was spudded on Block 1 during December 2010. The well was delayed, due to drilling problems, but it successfully reached a TD of 4,933 m in Feb. 2011, and was plugged and abandoned as a gas discovery. The partnership between Ophir and BG, had agreed that following the results of the three-well drilling campaign, BG would have the right to withdraw from the PSA or assume operatorship for Blocks, 1, 2 and 4. BG elected to assume operatorship of the blocks, following the success of the first three wells, in July 2011.

Following the three discoveries offshore, the Nyuni-2 well was drilled onshore on the Nyuni license, operated by Aminex. Some technical difficulties were encountered in the well, which was then sidetracked and subsequently suspended. Nyuni-2 did encounter indications of gas.

The next well to be drilled offshore Tanzania was a wildcat operated by Petrobras in Block 6. Zeta-1 was Petrobras’ first well offshore and was targeting a Lower Cretaceous reservoir, with Upper Cretaceous and Tertiary plays as secondary objectives. The well was plugged and abandoned as dry in December 2011. Following Zeta, the Ntorya-1 well was drilled by Aminex on the Rovuma license, which covers two onshore blocks, Lindi and Mtwara. The well was drilled to a depth of 2,026 m and did not encounter the targets as expected. The well was deepened a further 250 m; however, partner Tullow Oil did not elect to participate in the deepening on the well. The well encountered a 25-m sand interval with 3 m of net gas-bearing pay.

In January 2012, Statoil, and its partner ExxonMobil, began a drilling campaign with the Zafarani-1 well offshore. The well was spudded on Block 2 and announced as a discovery of 5 Tcf of gas-in-place, with a further addition of 1 Tcf of gas after sidetracking. Statoil followed Zafarani with the discovery of gas in Lavani-1 in June, again on Block 2. Lavani encountered “95 m of excellent quality reservoir sandstone with high-quality porosity and permeability.” The discovery of Lavani adds a further 3 Tcf of gas initially-in-place to Block 2.

The fourth gas discovery by the BG-Ophir consortium, this time operated by BG, was announced in March 2012. Jodari-1 was spudded in Block 1 and exceeded pre-drilling recoverable estimates, ultimately raising the gross recoverable resource estimates of the combined four discoveries over Blocks 1, 3 and 4 to up to 7 Tcf.

The Deepsea Metro rig, used to drill Jodari, was then moved to complete the Mzia-1 well on Block 1. Mzia was announced as the fifth consecutive discovery for BG and Ophir offshore Tanzania. Mzia adds an estimated 4-9 Tcf of gas-in-place. Following the discovery of Mzia, the consortium announced that the total in-place resources in Blocks 1, 3 and 4 meet the requirements of a two-train LNG development.

BG and Ophir’s fifth success offshore Tanzania came with the Papa-1 well, which was drilled in May 2012 as the first well on Block 3. This gas discovery reached a TD of 5,544 m. Following the appraisal drilling of Lavani, Statoil and Exxon have most recently announced their third gas discovery in offshore Block 2. The Tanzawizi-1 well was announced as a gas discovery in March 2013, raising volumes of recoverable gas resources to 10-13 Tcf in Block 2.

Future plans. During 2013, Tanzania will see further wells drilled offshore, appraising and testing existing discoveries. BG and partner, Ophir, are planning a drill stem test (DST) of their Jodari and Mzia fields. The consortium will also drill wildcat wells during the year, starting with the Ngisi-1 well on Block 4, which aims to appraise the Chewa discovery. It is thought Ngisi will be drilled with two deviated well paths. Ngisi-1 should be followed by a well on Block 1. The East Pande Block and Block 7, both operated by Ophir, will also have new wells drilled. The Mlinzi prospect on Block 7 and the Maembe well on the East Pande block are anticipated to be drilled in fourth-quarter 2013. Maurel et Prom is hoping to spud two wells, one on the Bigwa Rufiji Block and one on Mnazi Bay. Afren is also looking to drill a well on its Tanga Block during the year, after completing further 3D seismic data.

MOZAMBIQUE

Thick sedimentary basins were discovered in Mozambique by explorers during the early 1900s. However, it wasn’t until 1948 that IOCs began exploring the onshore basins. In the 1960s, three gas discoveries, Pande (1961), Buzi (1962) and Temane (1967), were made by Gulf Oil Company (now Chevron). At the time of discovery, these gas fields were deemed non-commercial, due to there being no feasible market in the country. Political instability affected exploration in Mozambique during the 1970s, which was restarted in 1980 when Mozambique’s state-owned oil company, Empresa Nacional de Hidrocarbonetors (ENH), was created. ENH began appraising Pande field in 1989 and, with increased knowledge of direct hydrocarbon indicators, allowed Pande field to be more accurately mapped. The technology was also used over Temane field in 1998, when the field was appraised. In 2000, Sasol took over operatorship of Pande and Temane fields and initiated an intensive drilling campaign to determine the field reserves. This campaign also led to the discovery of Inhassoro gas field in 2003.

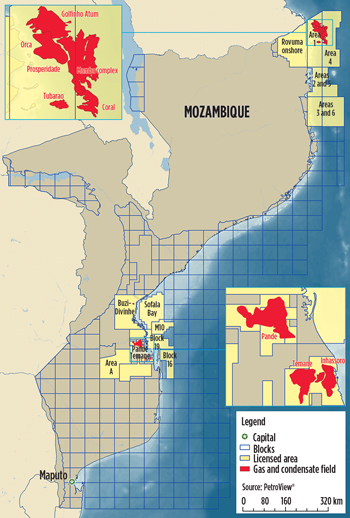

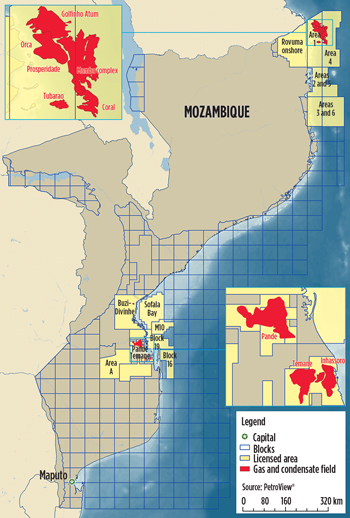

Licensing activity and key players. Blocks in Mozambique have traditionally been awarded through competitive licensing rounds, Fig. 5. To date, four rounds have been held in Mozambique. ENH held the first offshore licensing round between March and August 2000. The round offered 14 blocks from the Mozambique basin, covering the Zambezi Delta area. The second round was launched in July 2005, promoting opportunities onshore and offshore in the Rovuma basin, in northern Mozambique. The area had not been licensed previously, and only one well had been drilled onshore. Five blocks were made available: four offshore (Areas 1, 3, 4 and 6) and one onshore (the Rovuma Onshore block). All five blocks were awarded in March 2006 to a group of companies including Artumas, now Wentworth Resources (Rovuma Onshore), Anadarko (Area 1), Petronas (Areas 3 and 6) and Eni (Area 4). A month earlier, in February 2006, Areas 2 and 5, also within the Ruvuma basin, were awarded to Statoil. The third round, announced in December 2007, offered nine areas (A to I), for which interested companies could apply in their entirety or in part. Two blocks, A and B, were onshore, another two blocks, F and I were in water depths of less than 600 m. The remaining five blocks, C, D, E, G and H, were in deep waters, in excess of 6,000 m. The round closed in June 2008, and one block, Area A, was awarded to the Sasol Group.

|

| Fig. 5. Offshore and onshore acreage in Mozambique |

Mozambique’s fourth round in 2009 offered seven onshore areas covering 146,000 sq km. All seven areas received bids following the close of the round in April 2010. However, only one bid was successful. DNO International was invited to begin EPC negotiations The company, however, has left the acreage. Figure 5 describes the acreage currently leased by Mozambique. Following the significant offshore discoveries, Statoil has farmed down a 25% interest in Areas 2 and 5 to Inpex Corporation as it prepares to drill a well this year. This is Statoil’s second farm-down of these blocks in the last year. The company farmed down a 25% interest to Tullow Oil during Aug. 2012, strengthening Tullow’s position in East Africa.

Petronas, operator of Areas 3 and 6, also farmed down a 40% interest in these blocks to Total in Sept. 2012. Petronas remains as operator with a majority interest of 50% in the blocks. ENH holds the remaining 10% interest. Anadarko and Videocon have a total of 20% interest available in Area 1 for farm-out. In neighboring Area 4, Eni has announced a joint study agreement with CNPC, which results in CNPC acquiring an indirect interest in Area 4.

Recent exploration. In 2009, operators, which were awarded acreage in Mozambique’s second round in the Rovuma basin, began their exploration drilling commitments. The first well to be drilled was Anadarko’s Windjammer-1 on Area 1. The well was announced as a discovery in March 2010, encountering natural gas pay exceeding 169 m. The field was subsequently appraised by the Windjammer-2 well in February 2011. The second well drilled on Area 1 was Collier-1, which was spudded in March 2010. The well was suspended at a TD of 3,200 m, due to concerns after encountering pore pressure issues above the predicted reservoir objective. Anadarko’s third well, Ironclad-1, penetrated 36 m of net oil and gas saturated sands. Geochemical analysis confirmed the presence of oil in the sands, which makes the find of liquid hydrocarbons at Ironclad the first documented in deepwater offshore East Africa. Anadarko followed Ironclad with the Barquentine-1 discovery, which encountered more than 126.8 net m of natural gas pay in multiple, high-quality Oligocene sands. This discovery was reported to be age-equivalent but separate from the Windjammer discovery. Barquentine-1 also encountered further pay in deeper Paleocene sands, which is thought to be part of the same accumulation as Windjammer.

The Lagosta-1 well was drilled next and announced as the third gas discovery in Area 1 in late 2010. Lagosta penetrated more than 168 net m of gas pay in high-quality Oligocene and Eocene sands. Following the Lagosta discovery, Anadarko reported that enough gas had been found in Area 1 to support an LNG development in northern Mozambique. The fourth discovery in Area 1 was made with the Tubarao-1 well and was announced as a separate play from the previous three discoveries. In early 2011, the Windjammer and Lagosta wells were re-entered, so that well cores could be obtained. Following this, appraisal drilling began with Barquentine-2 and Camarao-1. Camerao-1 confirmed pressure connectivity with the Windjammer and Lagosta discoveries. A total of 73 m of gas was confirmed in the appraisal section of the well. Camarao also encountered a further 43 m of previously undiscovered gas in shallower Miocene and Oligocene sands.

While appraisal drilling continued in Area-1, Eni and its partners in the adjacent Area 4 began their exploration program. Eni spudded the Mamba South-1 well in August 2011 and in October, announced the discovery of a giant gas field, the largest operated discovery in ENI’s exploration history, with at least 15 Tcf of gas-in-place. This figure was later revised upwards to a potential 22.5 Tcf of gas-in-place. Mamba South was followed by the Mamba North-1 well and, in February 2012, a new giant gas discovery was announced. This discovery increased volumes of gas-in-place in the Mamba complex to 30 Tcf. Mamba North East-1 was the next well to be drilled in March 2012. The well discovered gas, which was in pressure communication with the first two Mamba wells. This discovery raised estimates of Mamba gas in place to 40 Tcf.

Coral-1 was drilled next. The well discovered 7-10 Tcf of gas in place after penetrating 75 m of gas pay in a single Eocene sand. The discovery is located exclusively within Area 4, and confirmed a new exploration play.

In June 2012, following successful appraisal drilling of nine wells in Area 1, Anadarko announced that the discovery in Area 1, combining Windjammer, Barquentine, Lagosta and Camarao, would be called Prosperidade, holding recoverable gas reserves of 17-30 Tcf. Following the Prosperidade appraisal, Anadarko spudded the Golfinho-1 well, which encountered 59 net m of gas pay in two Oligocene fan systems. This discovery is reported to be age-equivalent, but geologically distinct from Prosperidade. The consortium then spudded the Atum-1 well, which encountered a 92-m net gas pay. Atum well results indicate that it is linked to the Golfinho discovery, creating the Golfinho-Atum complex, located entirely within Area 1, with 10-30 Tcf of recoverable gas resources. Anadarko’s first 2013 well, Orca-1, discovered 50 m of natural gas within the Area 1 block. However, its Barracuda-1 and Perola Negra-1 wells encountered high-quality, but water-bearing reservoirs.

Future plans. Anadarko has an intensive drilling campaign planned for 2013, which includes four to five exploration wells and two to three appraisal wells. Wildcat wells on the Cavala, Enchova and Linguado prospects within Area 1 are expected during the year, in addition to further drill stem tests (DSTs) within the Golfinho-Atum complex. In Dec. 2012, Anadarko and Eni signed a heads-of-agreement for the joint development of common resources spanning their respective Areas 1 and 4. Statoil, operator of Areas 2 and 5, is also gearing up to drill its first two wells, beginning with the Cachalote-1, which was spud in April 2013.

CONCLUSIONS

While there have been major offshore gas discoveries and promising onshore results, the East African region remains vastly underexplored, and it will take years of further intensive exploration for the industry to learn of the region’s full potential. These three focus countries are looking to attract further investment from IOCs and independents, and as such, licensing rounds in all three countries are anticipated. If successful, these rounds will serve to bolster interest and further de-risk the region.

|

The author

LYDIA THEVANAYAGAM is the Sub Saharan Africa team leader for Deloitte’s Petroleum Services in London. She works directly on the development and maintenance of PetroView Sub Saharan Africa, a GIS database which tracks oil and gas activity across the region. Ms. Thevanayagam joined the Petroleum Services in 2007 after graduating from the University of Southampton with an MS degree in geology. /lthevanayagam@deloitte.co.uk |

|

BG optimistic on Tanzania prospects, LNG exports

IAN LEWIS, Contributing Editor, EAME

BG Group’s drilling campaign in offshore Tanzania has enjoyed recent successes. Derek Hudson, President and Asset General Manager of BG East Africa, tells World Oil that he believes there is more gas to come and that a proposed LNG plant can become a reality—if some tough challenges can be overcome.

Tanzania has not yet produced offshore gas reserves on quite the scale found in neighboring Mozambique, but a string of finds made by explorers in the east African nation over recent months means that talk of LNG exports is fast solidifying into a concrete plan. Barely a month goes by without BG and its partner Ophir Energy announcing success with an exploratory or appraisal well on its Blocks 1, 3 and 4, or Statoil and its partner ExxonMobil group striking gas on its acreage between them in Block 2, Fig. 4.

Hudson says he is “cautiously optimistic” that a planned LNG project to be developed with Statoil can be brought to fruition. “We are still three to four years away from sanction, but so far, all our discussions with the government with respect to drilling approvals and conversations over the benefits of a deepwater LNG project have been very constructive,” he says.

|

| BG’s Hudson: “Tough challenges, but we’re cautiously optimistic.” |

BG, Statoil and their partners have drawn up a list of six possible sites for an LNG plant along the coast adjacent to their blocks and are currently in talks with the state-owned TPDC to decide on the best one. Hudson says he hopes a site will be proposed to the government “in the next couple of months”.

With next-to-no relevant infrastructure on the ground and a welter of diverse elements to be studied first, it will be an expensive and time-consuming project. “When you are doing the evaluation, there are several factors to be considered: the adjacent communities, the livelihoods of the people there, cultural sites nearby, offshore bathymetry, onshore topography, borehole conditions, wave and current conditions—I could go on,” says Hudson.

Government collaboration. Reaching an accord with the government over gas revenues and domestic supply is a crucial part of the process still to be completed. While a new government policy governing the upstream energy industry is expected to emerge late 2013, a recently-circulated revised draft of the Ministry of Energy and Minerals’ policy for the mid and downstream natural gas industry—now with the government for approval—outlines several issues affecting gas producers.

Prime among these issues are calls for the domestic market to be given priority over the export market in gas supply and the creation of a gas aggregator to develop, own and manage the pipeline network, gas processing facilities and central gathering stations. Hudson describes the policy as a step in the right direction towards creating a framework within which direct power generation could exist along side other uses for gas, such as fertilizer or cement production, while still allowing more expensive difficult-to-develop deepwater gas to go toward LNG exports.

The exploration companies are still investigating what a new element in the revised policy, calling for firms participating in “the natural gas value chain” to be listed on the Dar es Salaam Stock Exchange, might mean for them.

BG and Statoil have also still yet to decide on the commercial structure of the LNG venture. Hudson says talks on collaboration were “heading in the right direction”. The company hopes to sell LNG primarily to Asian nations, with a particular eye on the Indian market, where gas demand is climbing fast and BG is building up a strong position in the local market. If a positive final investment decision is made in around 2017, then Tanzania could expect to be exporting LNG by early 2020s. But with the size, as well as the location, of a potential plant yet to be agreed on, along with many of the terms on which gas will be produced, the timetable is not set in stone. “The size of the plant is still up for debate, because we are still drilling,” says Hudson. The company is sticking with its estimate of 10 Tcf of reserves on its blocks at present, but may be able to push that figure higher as its campaign progresses. Statoil has estimated its acreage could hold total recoverable reserves of 10-13 Tcf.

Future drilling prospects. BG is now completing the drilling of its tenth well, an exploratory and appraisal well on Block 4, adding to six exploratory wells and three appraisal wells across its acreage, all of which have yielded gas. The Deepsea Metro-1 drillship will drill another exploration well and another appraisal well on Block 4 before being transferred to acreage operated by Ophir, and then to Kenya, where BG plans to drill two wells in its acreage there, Fig. 6. It is is due to return to Tanzania to renew BG’s campaign there in the second half of 2014.

The companies recently extended their contract for the Deepsea Metro I, which had been due to run out in June, for at least another 18 months. Contracted from Odfjell Drilling, the drillship been tailored to meet BG’s needs. Its dual-derrick capability helped reduce drill times and it has enough deck space to allow relatively easy installation of test equipment. “With several of the wells, even in 1,500 to 2,000 m of water, we could still drill them in 30 to 35 days, which is quite a feat,” Hudson says. The vessel was also “hardened” to provide defense against possible pirate attacks, of the sort more frequently experienced in waters further north towards the Horn of Africa.

As drilling continues, the company will also be assessing data from its existing wells and assessing a fresh batch of seismic data from Tanzania’s Block 1, due to be analyzed in mid-2013. As Block 1 is adjacent to large gas finds made in the Rovuma basin in northern Mozambique, BG is eager to see whether its acreage includes a continuation of that area’s Tertiary basin-floor fan. It is also considering carrying out further seismic surveys on Block 4 in 2014.

Tricky drilling conditions. BG’s acreage covers both tertiary and cretaceous geology, where drilling conditions have proved tricky at times. There is varied depositional environment, especially in the tertiary deposits and a series of structural features to be navigated. Parts of offshore Tanzania resemble “a Grand Canyon underwater,” Hudson says.

Active sedimentation is occurring on the sea bottom, leading to potential slope collapse. “As a result, there are bottom currents that can be quite challenging,” says Hudson, adding that he expects conditions to be just as tricky, if not more so, in Kenya.

Companies successful in bidding for the next round of Tanzanian acreage, due to be auctioned by the government in late 2013, can also expect to face tough drilling conditions. Those seven blocks are to the west of the existing exploration acreage, in water up to 3,000 m deep, roughly matching the maximum depth of BG’s current acreage. This round was originally scheduled for late 2012, but was postponed to allow the government to draw up a new oil and gas policy.

BG will be among companies taking an interest. “I don’t think that all of the best acreage has been taken up and we continue to look for additional opportunities,” Hudson says. The company will also be keeping an eye on further Tanzania farm-in possibilities should they come up, he added. BG initially entered the Tanzanian offshore sector in 2010 by farming into Ophir’s Blocks 1, 2 and 4, taking a 60% stake and operatorship.

Local needs. The need for operators to address the concerns of Tanzanians themselves and get their public relations right has been highlighted by recent unrest in the Mtwara region of southern Tanzania, an important center for BG’s operations. Concerns that a pipeline being built to take gas from a small existing gas project in Mnazi Bay to the rest of the country would not benefit the local community has led to riots.

Neither the field or the Chinese-financed pipeline are linked to BG or the other big offshore explorers, and the riots were not aimed at them, but gas producers will be left in no doubt that local interests must be given considerable weight to ensure their projects develop smoothly and that security risks are minimized.

BG is studying what role it can play in areas directly affected by its operations and in the country more generally. “We are doing a lot of capacity building at all sorts of different levels, from the vocational training we are doing in Mtwara and Lindi to providing scholarships,” Hudson says.

BG is also planning to recruit Tanzanians, where they are suitably qualified, and may look at trying to tempt Tanzanian engineers living overseas to return home. The company is about to hire its first set of Tanzanian graduates as part of its wider BG Group training program.

Hudson says BG is also keen to offering expertise gained in developing power projects in other poorer parts of the world to assist in developing power generation in Tanzania, where less than 15% of the population of 46 million has access to electricity, and to look at providing assistance to help train Tanzanians to acquire the skills needed in the power sector.

Economic impact. BG has been working with the Oxford Policy Management Group to prepare an assessment of the potential impact of a deep-water LNG project on Tanzania, a country with limited existing economic resources, or financial and physical infrastructure. Analysts estimate a two-train LNG plant, of the sort that Tanzania’s currently known reserves might merit, costs $10-15 billion or more in many parts of the world these days. That sort of figure would be a significant financial injection for a country with an annual GDP of about $24 billion.

As well as assessing the overall economic impact of offshore gas development, the study covers elements such as the estimated revenues generated for the government at different LNG prices, how best to deal with those revenues, educational requirements and the personnel and skills needed for construction and operation of the plant.

Hudson says preparing the report, which is being shared with TPDC and government ministries, is part of BG’s responsibilities to make sure the country was ready for “an influx of investment and potential cashflow that will dwarf anything that has transpired in Tanzania before”.

|

|