The risk of kidnapping: What oil companies need to do

Despite recent media focus on the In Aménas gas plant attack, there are also many other security threats that face overseas workers, especially in the form of kidnapping for financial gain.

|

TESS BAKER and SAM COLLARD, NYA International

In the early hours of Jan. 16, 2013, a group of Islamist militants linked to Al Qaeda’s North African franchise—Al Qaeda in the Islamic Mahgreb (AQIM)—hijacked a bus transporting workers from the Tigantourine gas facility, 40 km southwest of In Aménas, Algeria, and close to the Libyan border. The militants did this with the likely intention of holding the workers for ransom and other concessions. Although the intended outcome ultimately failed, the subsequent, bloody hostage siege that ensued was so shocking and unprecedented, that it has prompted many energy companies, and those organizations supporting the industry, to look more closely at security threats to personnel. HIGH-RISK AREAS Kidnapping flourishes where there is widespread poverty and polar disparity of wealth; active criminal and/or terrorist groups; and high levels of corruption and ineffective law enforcement. It is, therefore, endemic in some of the energy industry’s core operating environments. For criminal and terrorist groups around the world, it is big business. According to the U.S. Under Secretary for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence, David S. Cohen, an estimated $120 million has been generated by terrorist organizations from ransom payments in the last eight years (much of which he attributes to AQIM). So what is the outlook in some of the key high-risk areas and what should energy companies be doing about it? ALGERIA AND THE SAHEL REGION Algeria has struggled with home-grown Islamic militancy for many years. Formerly known as the Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat, or GSPC, AQIM is dedicated to overthrowing the Algerian government and establishing an Islamic state. The group has increasingly relied on kidnapping for ransom of foreign nationals to fund its operations. It has carried out attacks across the Sahel region (an area of North Africa that stretches from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the east, covering parts of Senegal, Mauritania, Mali, Algeria, Niger, Chad, Sudan, South Sudan and Eritrea). Militant activity in Algeria has typically been concentrated in the country’s northern Djebahia region, and energy companies have (largely) not been targeted, which is why the recent incident came as a surprise. However, this incident is more likely to be symptomatic of the deteriorating security situation in the wider Sahel region, rather than in Algeria specifically. The risk of kidnapping of foreign nationals across the Sahel region is at an all-time high, due to a combination of factors. First, the internal conflict in Libya has created a surplus of arms and war-hardened militants, many of whom have now dispersed into neighbouring Sudan, Chad and Niger. They are ready to conduct attacks and kidnappings for a multitude of Islamic militant groups. Second, the occupation of northern Mali by Islamist militants has effectively created a security vacuum and a staging ground for their operations. This is not dissimilar to the situation in Afghanistan, where the Taliban and Al Qaeda were able to put down roots. While ongoing military operations by French and African troops have succeeded in dislodging the militants, the latter have moved into the northern periphery of Mali, Mauritania, Burkina Faso, Niger and (to a lesser extent) Algeria. In these places, they are likely to launch a sustained campaign of “hit-and-run” attacks across the region. The economic importance and profile of the energy industry in the region makes workers an obvious “target of opportunity” for militants. As long as the region remains awash with weapons and trained militants, while, at the same time, security forces are unable to effectively control such a vast area, the threat will likely remain high. SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA: NIGERIA

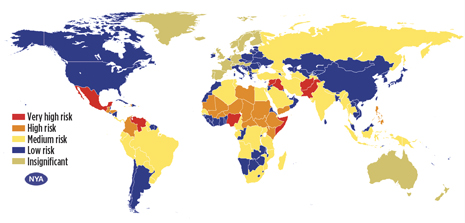

Of all oil-producing countries, the threat of kidnapping has always been highest in Nigeria. Ranked among the some of the highest countries for kidnapping and ransom risk in the world (Fig. 1), the crime has reached epidemic proportions. Most incidents have traditionally taken place in the volatile southern Niger Delta region, Fig. 2. Rebel groups operating under the umbrella of the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND) originally kidnapped foreign oil workers in protest against the perceived exploitation of resources, and the lack of economic development and wealth distribution. While dressed as political, the nature of their demands were largely financial. Following a governmental amnesty program in 2009, which incentivized rebels to cease their activities, attacks on oil installations and kidnappings declined. However, many lower-level rebels were excluded from the program and have formed criminal groups that continue to carry out kidnappings. As a result, nearly all kidnappings in the Niger Delta region are now carried by low-level gangs or former-MEND rebels. According to Nigerian state police reports, approximately 350 kidnapping cases were recorded between January 2011 and May 2012 in Delta State, alone. Workers in the oil and gas sector continue to be abducted, not only on land but also at sea, as part of the growing trend of piracy in the Gulf of Guinea. The primary goal of the West African (largely Nigerian) pirates is the theft of the ship’s cargo and stores, and the crew’s valuables. Seizing vessels for ransom, the modus operandi of Somali pirates around the Horn of Africa, is deemed to be unlikely in West Africa, given the high value of oil cargo stolen and sold on the black market. However, there has been a recent spike in the number of piracy attacks in the Gulf of Guinea, in particular cases of crew members being removed from vessels and held for ransom on land. Between Feb. 7 and Feb. 17, 2013, pirates attacked three separate vessels and kidnapped 11 crew members (all foreign nationals). As this article goes to print, it is reported that all 11 hostages are being held on land, with a ransom demand of $1.3 million for six of the crew abducted in the third attack. LATIN AMERICA: COLOMBIA For years, Colombia has been synonymous with kidnapping. At the height of its influence, the country’s oldest, left-wing rebel group, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), numbered some 18,000 armed combatants, with a further 8,000–10,000 persons in non-combatant logistical support roles. Although the group was traditionally motivated by its political aims, this morphed into financially motivated kidnapping for ransom. In 2000, kidnappings attributed to FARC numbered 1,078 (according to official statistics from the Colombian Ministry of Defense “Fondelibertad”) out of 3,572 recorded incidents for that year. Following the U.S.-backed “Plan Colombia” (a U.S.-Colombian aid initiative involving U.S. military / counter-narcotics support in the form of funding, training, equipment and other services, which came into effect in 1999), the situation has improved significantly. By 2002, FARC kidnappings had been reduced slightly to 973, and then fell sharply to 319 by 2004. In early 2012, FARC officially renounced kidnapping for ransom and is currently in peace negotiations with the government although many commentators (having seen similar initiatives in the past) are skeptical as to whether or not meaningful results will be achieved. Vast areas of land have opened up for oil and mining exploration, and Latin America’s fourth-largest oil producer saw foreign investment go up from circa $2 billion in 2002, to nearly $16 billion in 2012. However, the problem is by no means solved. The National Liberation Army (ELN)—a smaller but not insignificant group with an estimated 3,000 members—is still actively targeting the energy sector. The number of attacks carried out by ELN rose in 2012, and the Colombian government now has around 70,000 troops dedicated to defending oil and mining operations. ELN is not part of peace talks being held in Cuba between President Juan Manuel Santos’ government and FARC, despite having asked to join the discussions. Some political commentators have suggested that the rise in kidnappings could be a pressure tactic by the group, to force the government to include them in the ongoing peace talks. Moreover, concern has been voiced over the continued levels of aid provided under Plan Colombia. If U.S. support should ever reduce, and if the peace process is not a success, FARC could possibly stage a resurgence. MIDDLE EAST: IRAQ Iraq has always had a criminal underground. Lessons have been learned from protection measures applied by the military, but oil workers are still attractive targets of opportunity. In the years immediately following the 2003 invasion of Iraq by coalition forces, abductions of Westerners usually resulted in the execution of the hostage(s), as the demands made were often for political concessions and/or prisoner release. However, since then, the crime has become financially driven, with increasing reports of release following ransom payments. In May 2012, four employees of a contractor company, working at a pipeline fabrication plant near Rumaila oil field, were kidnapped at a checkpoint and held for more than a month. All four were released, unharmed, after the reported payment of a $500,000 ransom. DUTY OF CARE Accurate global statistics about kidnapping do not exist: many incidents go unreported, and the figures that national authorities do hold are not widely publicized, for obvious reasons. However, numerous sources cite tens of thousands of incidents, worldwide, each year. “Kidnapping is a risk that major energy companies are very familiar with, and they have the experience and resources to manage it effectively. Not so for smaller companies and sub-contractors,” said Mark Carlson, a consultant from NYA International (NYA), a crisis prevention and response consultancy, with many years’ experience of advising organizations impacted by kidnap and extortion risks. “They are often going into these high-to-extreme risk environments without completely appreciating the threat or their possible exposure to kidnapping, and are putting their people at risk.” “Their basic security arrangements may well be taken care of by the prime contractor, but in the event of an incident, it is not necessarily the case that the prime-contractor will assume all responsibility for each individual. Even if they do, the subcontractor will still have their own issues to deal with, such as assisting the victim’s family, for example. The smaller subcontractors still have a Duty of Care, to their people, but this can be something that is overlooked. We’ve seen it happen time and time again, and in the event of an incident, the organization is often unprepared, risking reputation and exposing the organization to unnecessary liability.” In the Niger Delta, there has been a number of high profile cases of kidnapped oil workers, who, after their release, have launched lawsuits against their employers for failing to address and mitigate the risk. This is a trend that we would expect to continue. While the financial settlement may be considered insignificant for those companies concerned, the reputational damage and impact on the rest of the workforce can be far more compelling. Fulfilling Duty of Care obligations toward employees begins with awareness. That means having a thorough understanding of the operating environment, and providing employees with the right information and personal security awareness training to help them stay safe. This applies to both expatriates and local staff — both carry different levels of risk. EMPLOYEE PROTECTION AND TRAINING Expatriate employees will almost always be attractive targets. They stand out, and their association to a wealthy oil company gives them a higher perceived value in the eyes of the abductors. On and enroute to sites, they are generally well-protected, although organized militant groups have mounted attacks on energy installations and supporting transportation (such as oil support vessels), as happens regularly in the Niger Delta. Workers are also targeted when outside the protective security umbrella provided by the prime contractor, in what are often opportunistic attacks. This usually happens when an individual, or group of individuals, breaks protocols, takes an unsanctioned excursion into local towns for entertainment, and gets caught in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Such opportunistic targeting, however, is relatively easy to address. With the right understanding of the area, good personal security awareness, and the implementation of practical precautions, you can significantly reduce your risk exposure. Joe Carrera, also a consultant with NYA, said, “The challenge is often with the experienced hands, the people who have been living and working in a country for years. They tend to adjust to the environment, their personal awareness and perception of the threat goes down, and they start to become complacent,” Fig. 3. “I have seen it happen to oil workers in Venezuela, Angola, Nigeria, Iraq— expatriates falling victim to kidnapping who have been in the country for a very long time,” said Carerra. “Those who have been in country the longest also tend to have wider social circles. Often they have integrated with the local community, which can lead to them having a false sense of security. People feel they are ‘accepted’ and therefore safe, when in fact, the more widely known you are, the wider your circle of vulnerability. “Local staff and their dependents are also susceptible,” Carerra continued, “and often have a very clear routine. The same bus takes workers to their compound, or the same barge takes workers to an offshore platform, at the same time, every day, and children go to school, or to the mosque at very predictable times. We’re seeing an increase in incidents involving children, who are particularly susceptible, because they are seen as ‘soft targets.’ And unlike opportunistic targeting, routine targeting is very difficult to stop, so specific actions are required to mitigate the risk.” The training of staff is generally addressed comprehensively by the major energy firms, but it is an area where the smaller, independent exploration companies are sometimes exposed, because they may not have a dedicated security department, so the issue is not always given the requisite attention. Personal security training should be provided across the board to full-time employees and contractors, people out there for the first time, and to the ‘experienced hands’. It should also be specific to the local site and operating environment, and take into account the particular considerations of employees’ expat or local status. Said Carrera, “The fundamentals are fairly straightforward, a lot of it is common sense: it’s about raising awareness and getting people to take responsibility for themselves. Preparing people in the event they're held hostage should be included, as well, to help mitigate the physical and psychological impact. As a victim, there are certain key things that you ideally should and shouldn’t do that can significantly improve your chances of survival.” BEST PRACTICE: OPERATING PROCEDURES/CRISIS PLANNING The next step for a company is to have detailed, standard security operating procedures written for each particular operating environment, which are regularly reviewed and updated. Said Mark Carlson, “It’s no good producing them and shutting them in a drawer, they need to be ‘living’ documents, adhered to and rigorously enforced. Some companies are more draconian than others in enforcing these procedures, but the fact is, if a company is serious about reducing their risk of kidnapping, they need to take a fairly hard-line approach. If you embed a culture of both awareness and personal responsibility, you really can have an impact on the level of risk.” At a corporate level, there should be a crisis management plan at the ready, and a crisis management team that understands what it needs to do in the event of an incident. Kidnapping is generally part of an organization’s crisis management plan, but it is not widely discussed in companies. It is viewed perhaps as being a confidential or sensitive matter, or the kind of low-frequency, high-impact event, that will hopefully never happen. However it is strongly advised that organizations undertake a practice run of a kidnapping scenario, via a simulated, table-top exercise, because there are particularities to an incident of this nature that are not normally inherent with a more technical crisis situation. Here, you are not dealing with the aftermath of an incident; a kidnapping is an ongoing, dynamic event. How you handle it—particularly in the early stages—is critical and directly affects whether the victims are released alive, how long they are held for, and the vulnerability of other employees to future attack. Moreover, the psychology of kidnapping negotiations may be counter-intuitive to some senior-level executives in the crisis management team, who are more used to driving hard business negotiations. The same applies to the level of emotion involved, said Carlson, “It’s high-impact in an emotional sense. A person has been taken—an employee, a colleague, a family member. The distress that it creates should not be underestimated. You need to give proper attention to assisting the families; getting it right is essential, not only for their welfare, but it may also have an impact upon the likelihood of litigation after the event. There’s a saying, ‘If you lose the families’ trust, you lose the case,’ and this is absolutely true.” Certain key decisions should be clarified in advance. When you are dealing with an incident, you do not want to be slowed down by trying to establish your company’s policy toward payment of ransom — know this in advance. You should also understand the likely logistics of an incident, according to the country you are in, including legal/legislative issues. You will need a media strategy, and decisions will need to be made regarding liaison with the local authorities. There is a lot to think about, and in the throes of an incident, things can unfold at an alarming rate. “It’s also not unusual to be thrown the odd curveball, a phone call from an unknown intermediary, an instruction from the kidnappers that you weren’t expecting,” said Carrera. “If you’ve anticipated and are clear on certain predictable issues in advance, you can focus your attention on the things you can’t anticipate. Above all else, it is important to prepare for the long haul and ensure that the organization can continue to function while attention is focused on this incident. “The key advice that we give smaller companies and subcontractors,” continued Carrera, “is to do their due diligence — make it a part of their entry strategy. Don’t just assume that the major you’re contracted to carries all the responsibility, and is going to do everything for you in the event of any incident. Understand where your company’s responsibilities will start and end, and be fully prepared to manage your own crisis if you have to.” “Don’t forget to look down the chain, too, to the subcontractors that are working for you,” Carrera added. “We’ve seen it happen in Colombia, where companies take on subcontractors, unaware that they’ve been making concessionary payments to FARC. Where this has happened, you end up taking on this problem, and distancing the organization from the issue can be very difficult. When the payments stop, that’s when the company is actively targeted in retribution, with attacks on assets or the kidnapping of staff. And with the huge numbers of private security companies operating in places like Iraq, it’s important to include any subcontracted protective security in your due diligence too.” Carlson agrees. “We still see a surprising level of naïveté about these risks, and companies that are caught unprepared. Don’t be under any illusion that it won't happen, or that it is someone else’s problem; it is critical that you take responsibility for the risks faced by your staff and their dependents. Be prepared.” |